On 25th July 1909, Louis Blériot, the French aviation pioneer, became the first aviator to fly across the English Channel in a heavier-than-air aircraft, Blériot XI monoplane.

On 25th July 1909, Louis Blériot, the French aviation pioneer, became the first aviator to fly across the English Channel in a heavier-than-air aircraft, Blériot XI monoplane.

Louis Charles Joseph Blériot was born on 1st July 1872, in Cambrai, France.

From his early years, Blériot was interested in engineering, being especially excellent in technical drawings. Already at the age of ten he attended Institution Notre-Dame (Notre Dame Institute) in Cambrai, then went to a high school in Amiens and the college Sainte-Barbe in Paris. In 1892, Blériot started his study at the prestigious École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures (Central School of Engineering and Science). He graduated three years later, receiving his engineer diploma and then attended compulsory military service in an artillery regiment.

After spending a year in the army, Blériot started to work for an electrical engineering company in Paris, known as Baguès. There, he made his primary significant development – an automobile headlamp, powered by acetylene generator. It was the first car lamp of that kind in the world and quickly started being widely adopted by automobile manufacturers. Blériot left the company and opened his own workshop, successfully selling his lamps to Renault and Panhard, two biggest car manufacturers in Europe at that time.

Blériot´s interest in aircraft started already during his studies at École Centrale but it was his successful business with automobile lamps that finally allowed him to focus more on aviation developments. Nevertheless, the beginning was tough and marked with some unsuccessful experiments. In 1901, he developed his first aircraft, Blériot I, that featured flapping wings and was powered by carbonic acid engine of his construction.

The early years of Blériot´s aviation experiences were influenced by two other aviation pioneers he met in the early 1900s – Ferdinand Ferber and Julien Mamet. It was Ferber who introduced Blériot to Gabriel Voisin, at that time working with Ernest Archdeacon on his gliders. This meeting led to creation of Blériot II, a glider made by Voisin for Louis Blériot.

Blériot and Voisin cooperated together on some further aviation developments and finally – with assistance of Édouard Surcouf, French industrialist, engineer and dirigible pilot – in 1905 decided to open their own workshop they named Ateliers d’ Aviation Édouard Surcouf, Blériot et Voisin. The company made two powered aircraft Blériot III and IV, designed by Louis Blériot and with Voisin being responsible for their mechanical parts. Regrettably, none of them was successful and at the end of 1906 the shareholders split off, closing the company. Gabriel Voisin, together with his brother Charles and some additional partners, founded Appareils d’Aviation Les Frères Voisin, while Blériot established his own company – Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot.

Within the next few years, Blériot experimented with several different configurations of his aeroplanes, engines and control systems. First of them was Blériot V, the aircraft of a canard design, and the series was concluded with Blériot XII made in May of 1909. Although some of the Blériot´s inventions meant significant progress in aviation development, he did not achieve any commercial success – quite the contrary. It was reported that during those years of aviation experiments, Blériot invested an enormous amount of 780,000 francs on his projects. For the sake of comparison, an average monthly salary of a male worker in 1911 was 150 francs. In the middle of 1909, Blériot (together with Voisin) received Prix Osiris for his contribution to science, but this did not improve his financial situation.

At the dawn of aviation, many big newspapers and magazines used to sponsor prizes for those who dared to push the limits forward. It was quite popular way to attract readers but, at the same time, stimulating the new inventions and adventures.

Although the powered, heavier-than-air aircraft was one of the latest and still fledging inventions, it quickly found its way to front pages of newspapers. The quarter mile out and return flight, the first flight across the English Channel, the first circular one-mile-flight, the longest flight performed by a woman pilot (Femina Cup), the first flight performed by British pilot in a British-made aeroplane, the first transatlantic flight – were only a few of aviation milestones that were motivated by newspaper-founded prizes.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Daily Mail – the British daily middle-market newspaper founded in 1896 – was among the most active sponsors of aviation competitions. Between 1906 and 1930, following the initial idea of Alfred Harmsworth, the owner of the Daily Mail, the newspaper set more than twenty aviation goals, each of them awarded by a considerable amount of money.

In October of 1908, the Daily Mail announced that pilot who would be the first to cross the English Channel in a powered aircraft, would be awarded a prize of 500 pounds. As there was no one to dare, next year it was increased to 1,000 pounds – a huge amount, being an equivalent of today´s 120,000 GBP. Nevertheless, it was considered by general public as just a smart marketing move, as no aircraft would be able to complete such flight. Surprisingly, shortly after receiving the aforementioned Osiris Prize, Blériot announced that he was going to cross the Channel yet that year.

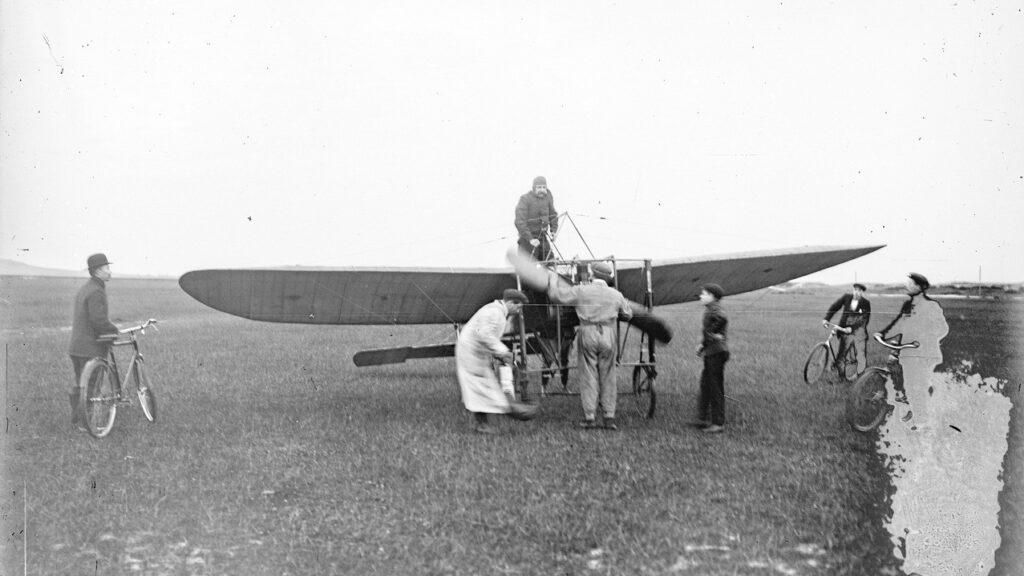

The aircraft he chosen for the flight was Blériot XI, a tractor-configuration monoplane with Anzani three-cylinder engine, generating 25 hp. The route was from Calais to Dover and the interesting fact was that Blériot had not visited England before, relying on Charles Fontaine, the journalist of Le Matine, to find a proper landing spot there.

However, the French aviation pioneer was not the only one who dared to go after the grand prize. On 9th July 1909, the English aviator Hubert Latham officially informed the Daily Mail editor about his intention to cross the Channel. He was then followed by Comte Charles de Lambert in a Wright Flyer.

Shortly after, the three aviators set camps on the French coast of the English Channel and waited for the favourable weather.

Latham postponed his flight several times, due to the weather conditions, and finally decided to take-off on 19th July. Regrettably, after only thirteen kilometres of flight, his Antoinette IV suffered engine failure and the French aviation pioneer ditched into the Channel waters. The aircraft remained afloat and soon after Latham was rescued by the French military vessel. Later, the powerplant of the Antoinette was examined and it was found that a stray piece of wire in the engine was the reason of its malfunction.

Undaunted, Latham acquired another aircraft, the newest Antoinette VII, which arrived on 21st July. He tested it briefly and waited for the fair weather to make another crossing attempt.

However, it was the Blériot´s team to note a break in the weather during the early morning of 25th July 1909. Blériot jumped into his aeroplane in a dare and, at 4:41 a.m., took-off for the first successful crossing of the English Channel.

Thirty six minutes and thirty second later, Blériot XI sucessfully landed near Dover Castle, flying over the Channel at an altitude of 250 feet.

It may sound a cliché, but Latham and his team literally slept over their opportunity to make an aviation history. The Daily Mail later reported that Léon Levavasseur, the well-known French engineer and aircraft designer who was part of the Latham´s team, was awaken at the time Blériot left the French coast. He alarmed the English aviator and the rest of the team but at the time they made the aircraft ready to fly and chase Blériot, the weather closed in.

Blériot´s flight was not only an another significant achievement in aviation but also brought fame and financial remuneration to the pilot. In a short time, the Blériot´s company received more than one hundred orders for Type XI aircraft. Recherches Aéronautiques Louis Blériot rapidly grew up and, until the outbreak of the Great War, made approximately 900 aeroplanes.

In addition, Blériot participated in several aviation meetings in Europe. He was the first one to show a flight of powered aircraft in Hungary and Romania, established new world speed record of powered aircraft, as well as was close to win the first Gordon Benett Trophy. Moreover, Blériot also founded aviation schools in France and the UK.

In 1913, just at the eve of the World War I, Blériot bought Société pour les Appareils Deperdussin aviation company and renamed it Société Pour L’Aviation et ses Dérivés, commonly known as SPAD. During the war, the company was successfully manufacturing fighter aircraft, including the well-known S.VII and S.XIII.

After the war, faced with decreasing demand for aircraft, Blériot´s companies switched to manufacturing cars and motorcycles, thus surviving the hard times. In the middle of 1920s, Blériot Aéronautique returned to build aeroplanes and continued with that activity until 1937. That year, as apart of nationalisation of French aviation industry, his company was taken over by Société nationale des constructions aéronautiques du Sud-Ouest (aka SNCASO or just Sud-Ouest).

Louis Blériot died on 1st August 1936, due to a heart attack.

Cover photo: Louis Blériot in his monoplane, 2 Oct 1908, photo: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France, ark:/12148/btv1b69111068)