On 28th October 1936, Dornier Do 19, four-engine long-range heavy bomber, performed its maiden flight.

On 28th October 1936, Dornier Do 19, four-engine long-range heavy bomber, performed its maiden flight.

Shortly following Hitler´s rise to power at the beginning of 1933 and then creation of the first Nazi-led cabinet, the new Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium – RLM) was established. In September of the same year, the post of its commander (Leiter des Luftkommandoamtes) was assumed by Walther Wever – an infantry officer with a quite long service history with the Prussian and Weimar republic armed forces, including the post of staff officer for the Army High Command (Oberste Heeresleitung) in the Great War.

Although being the infantry officer, he quickly adapted to the air force specifics and needs. Bearing in mind Hitler´s ideas of Lebensraum (English: living space) that had to be created by German territorial expansion into Eastern Europe, Wever not only expected the war with the Soviet Union but also realized the size of future theatre of war. He was also convinced that German troops would not be able to advance beyond Moscow, therefore allowing a significant part of Soviet industry to continue its production.

As a consequence, Wever not only recognized the importance of long-range aviation but became an ardent supporter of strategic bombing doctrine, created by Giulio Douhet, an Italian general and aviation theorist. According to Wever, a fleet of four-engine heavy bombers had to be created, allowing the German air force to perform long-range raids into Soviet territory and destroy targets such as aviation factories, railways, mining facilities or heavy industry. Since many of those targets were located near (and beyond) the Ural Mountains, the programme of heavy bomber shortly received a common name of ´Ural Bomber´.

However, it seemed that Wever was the only supporter of the heavy bomber programme within the entire RLM. Other German aviation authorities and strategists preferred to focus on smaller aircraft, powered by two engines and having significantly shorter range. One of the reasons was that many high officials of the RLM were the Great War fighter pilots – such as Hermann Göring, Ernst Udet or Hans Jeschonnek – and they were familiar only with tactics and operational usage of frontline aviation.

Another reason were resources, necessary to create the fleet of strategic bombers. They required bigger budget, more manpower and material, while resulting in smaller number of aircraft built. In the challenging environment of political wrangling and intrigues among the Nazi officials, ability to create an imposing fleet of small aircraft and then submitting that number to Hitler himself, could significantly affect one´s carrier.

That situation did not change even with creation of the Luftwaffe, in March of 1935, and Wever´s appointment for its Chief of Staff (Chef des Generalstabes der Luftwaffe) that followed.

Nevertheless, Wever had not intended to abandon his ideas. He not only started some unofficial negotiations with Dornier and Junkers, supporting their plans to design the four-engine bomber, but in late 1935 also led to place an official order for two prototypes of Ural Bomber.

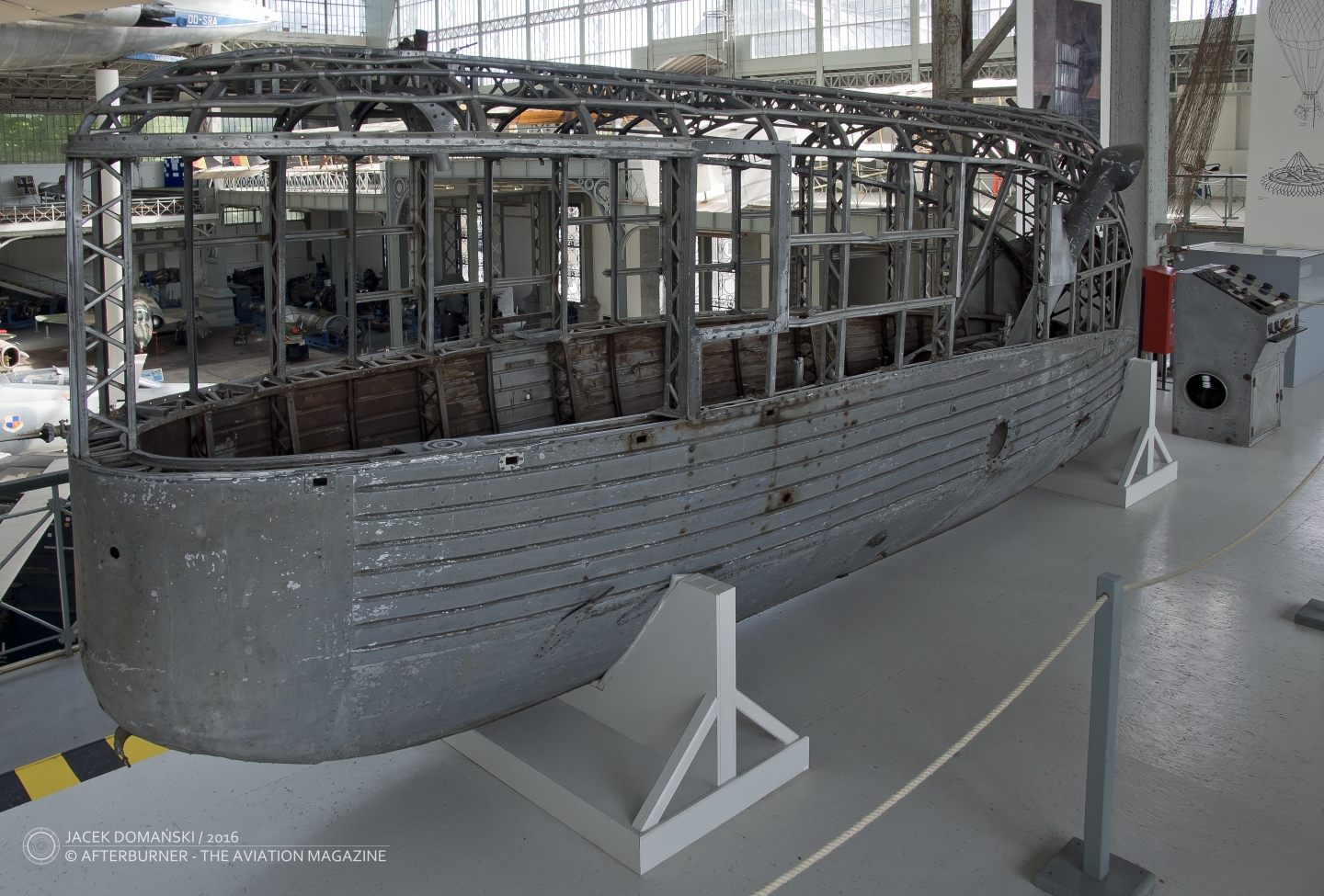

Already a year earlier, the Dornier company made a mock-up of a heavy bomber and then presented it for the RLM officials. Now, the project could be officially continued, and the new aircraft was designated Do 19. It was a mid-wing, cantilever aeroplane with retractable landing gear and braced twin fin tail with rudders. The aircraft had to be operated by a crew of ten.

Three prototypes of the Do 19 were made, designated V1 to V3. The V1 made its maiden flight on 28th October 1936 but performance of the new aircraft was disappointing. The Do 19 was slow, engines were not efficient enough and, as a consequence, it could carry only with only 1,600 kg of bomb load and had the range far below the strategic needs.

Junkers´ design seemed to be more promising. The first prototype of aircraft designated Ju 89, performed its maiden flight on 11th April 1937. A year later, the second prototype set some world records in payload/altitude category, achieving 30,551 feet with 5,000 kg load and then 23,760 feet with 10,000 kg.

Regrettably, Walther Wever never lived to see any of those heavy bomber prototypes in flight. On 3rd June 1936 he died in an aviation accident, flying Heinkel He 70 Blitz.

After Wever´s death, RLM lost interest in development of both German heavy bombers. The Dornier and Junkers companies made their prototypes airborne but that was all they could do without support from the Luftwaffe and government.

In 1938, two prototypes of the Ju 89 and one prototype of the Do 19 were taken over by Lufthansa and, for a short time, used for cargo transport purposes. A shortly earlier, the V2 and V3 prototypes of the Do 19 were scrapped. Eventually, the aeroplanes used by Lufthansa suffered the same fate and they did not make it beyond 1939.

Without Wever, the RLM high officials did not care about the heavy bombers anymore. The German doctrine focused solely on development of tactical aviation, being able to destroy the enemy air force and support the ground troops in their advance. As mentioned by David Irving (The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe, 1973), Göring emphasized the end of German strategic aviation with saying ‘The Führer does not ask me how big my bombers are, but how many there are’.

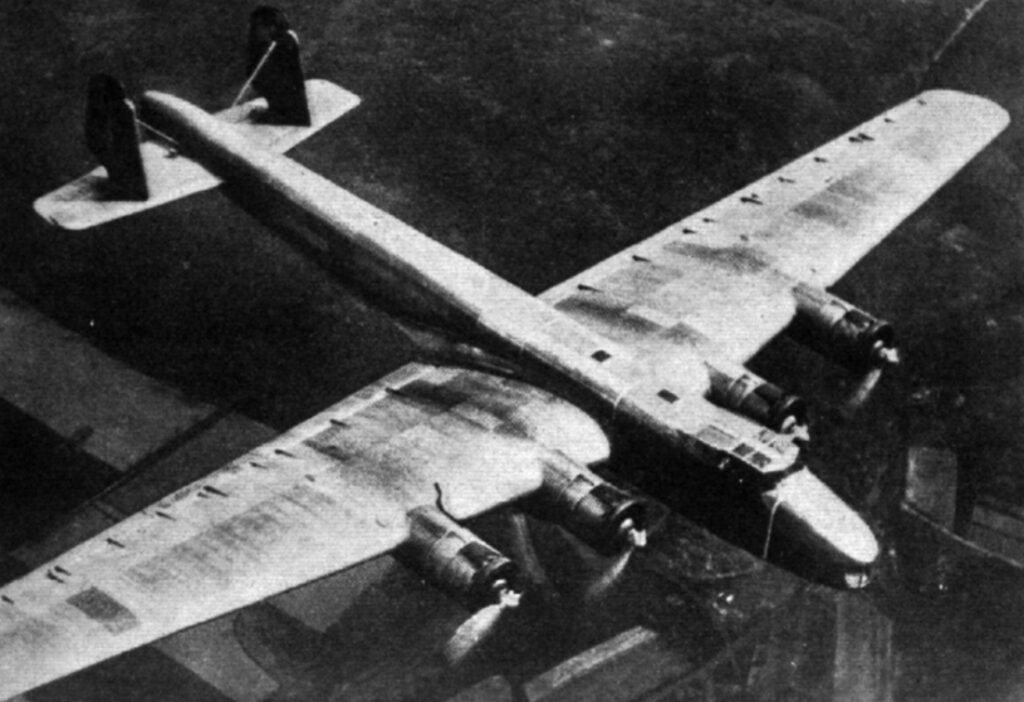

Cover photo: Dornier Do 19 in flight (Wikipedia, Public Domain)