On 8th July 2011, STS-135 – the final mission within the NASA Space Shuttle programme – was launched, with the space shuttle Atlantis making its final flight into space.

On 8th July 2011, STS-135 – the final mission within the NASA Space Shuttle programme – was launched, with the space shuttle Atlantis making its final flight into space.

The idea of the space shuttle originated yet back in the days of the US manned flights to the Moon, within the NASA Apollo programme started in the late 1960s. The new spacecraft was supposed to provide a relatively low-cost way for NASA to launch both people and cargo into low Earth orbit, with a rapid turnaround of the space vehicle between flights.

The NASA Space Shuttle programme officially began, and was announced to the public, in 1972. Five years later, in February 1977, the first atmospheric landing test of the shuttle took place with an experimental orbiter named Enterprise, launched together with specially modified example of Boeing 747. On 12th April 1981, orbiter Columbia launched into space with the first official mission within the NASA Space Shuttle programme, marked STS-1.

Since then, the space shuttles became the core of the US manned spaceflight for the next 30 years. During that time, those spacecraft had a significant impact on human exploration and understanding of the universe by carrying equipment and experiments – such as the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, or the interplanetary probes named Galileo, Magellan and Ulysses – into space. In addition, due to their involvement in development of the Soviet space station ‘Mir’ and then establishment of the International Space Station, as well as providing supplies and transporting subsequent crew members to those stations, the NASA space shuttles have directly contributed to humans’ permanent presence in space.

Unfortunately, and despite the aforementioned credits, the space shuttles turned out to have significant downsides. First of all, there were the operational costs of the vehicles.

Over time, the NASA Space Shuttle programme became extremely expensive. The average cost per space shuttle launch was approximately $1,5 billion, that was far in excess of the initially estimated costs. Vehicles that were supposed to be a cheaper alternative to conventional rockets, have in many cases turned out to be a more expensive option. That led to a decrease of interest among potential customers, as those initially keen to launching their devices into orbit with the shuttle, were finally opting to use a rocket instead.

The second issue was the time it took for the spacecraft that returned to Earth to be ready for launch again. Initial assumption was that this time could be as short as two weeks. However, in fact the shortest turnaround time during the entire service of the space shuttles was 54 days.

Another thing was safety of those spacecraft themselves. Although yet in the mid-1980s crewed space shuttle flights became practically routine and the vehicles were widely considered to be very safe to fly on, events that occurred in the following years changed this opinion.

On 28th January 1986, the Challenger orbiter exploded shortly after lift-off. Seventeen years later, on 1st February 2003, the space shuttle Columbia broke apart during re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere while returning from a mission. In both cases, all crew members of the spacecraft were killed.

Although the causes and circumstances of the Challenger and Columbia catastrophes were different, they brought the safety of the shuttles into question, until it was finally recognised that it was actually never completely safe to fly them. Not insignificant in that case were serious safety culture problems within NASA itself, the existence of which came to light during one of the investigations after the first of the abovementioned catastrophes. Investigation following the second shuttle disaster, unfortunately, confirmed those problems still existed.

Despite some efforts made by NASA to make shuttle flights safer, the aforementioned high operating costs, decreasing customer interest and, above all, fatal catastrophes, ultimately led to the end of the space shuttles era.

On 14th January 2004, the then US President George W. Bush announced his Vision for Space Exploration. It was motivated primarily by the Columbia shuttle disaster that had occurred less than a year earlier, as well as the state of NASA crewed spaceflights at the time and will to regain public enthusiasm for space exploration.

The main premise of President Bush’s space exploration plan was to retire the space shuttles, as soon as the International Space Station (ISS) was completed, as those spacecraft had crucial role in its development. However, it took several more years before the end of space shuttle era had come. In March 2006, it was estimated that sixteen more shuttle flights would be needed to finish construction of the ISS. In October of the same year, another space shuttle flight was approved with one additional service mission to the Hubble Space Telescope.

Due to uncertainty about whether Congress would decide to allocate funding for further space shuttle missions, STS-134 involving Endeavour orbiter to carry experiment equipment to the ISS, between May and June 2011, was initially expected to be the final space shuttle mission.

However, at the turn of 2010 and 2011, NASA decided that due to possible delays in development of commercial rockets and other spacecraft capable of transporting payloads to the ISS, yet another mission to the station was needed and would take place regardless of the financial situation. Eventually, the amount of money in the federal budget for 2011 intended for NASA space operations turned out to be sufficient and finally dispelled any doubts about whether the mission would be carried out.

Yet on 14th October 2010 it was decided to eventually convert the not-flown Launch on Need (the LON missions that were introduced after the Columbia orbiter disaster as an additional safety measure) STS-335 mission involving Atlantis spacecraft – intended as potential rescue mission for the aforementioned STS-134 in case of any emergency – for standard mission designated STS-135. Therefore, the crew assigned to STS-335 was additionally prepared to take part in regular spaceflight.

That crew was Commander Christopher Ferguson (the third spaceflight), Pilot Douglas Hurley (the second spaceflight), Mission Specialists Sandra Magnus and Rex Walheim (for both that was the third and last spaceflight).

While the standard shuttle crew consisted of 6 to 7 people, in this case it was decided to keep the original four-person crew from LON STS-335. The reason for this was the lack of other shuttles that could be assigned to rescue mission for the STS-135 crew. Orbiter Discovery launched for the last time on 24th February 2011, while for the Endeavour shuttle, the STS-134 was the last mission from which it returned on 1st June 2011, one month before the planned launch of STS-135.

Consequently, if the Atlantis en route to the ISS would suffer a damage threatening a safe return, the STS-135 astronauts were to return to Earth from the station one at a time aboard Russian Soyuz spacecraft over the course of a year.

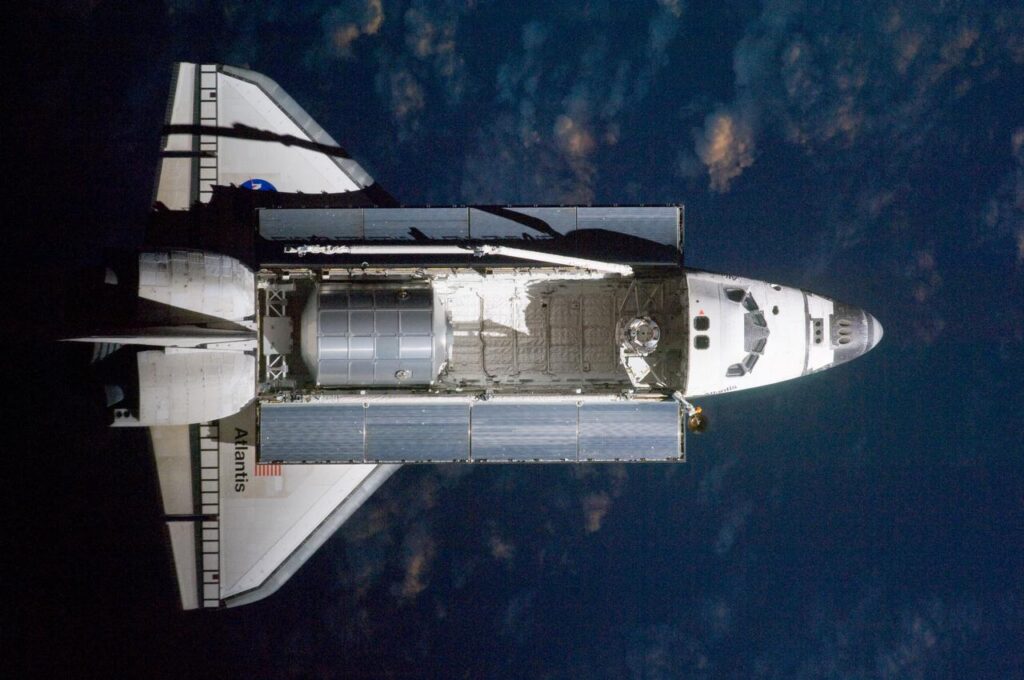

With NASA Space Shuttle programme just coming to an end and the then lack of US alternatives in terms of the further ISS resupply possibilities, the main task of the STS-135 mission was to deliver equipment and supplies to the station sufficient until 2012. That was possible thanks to Multi-Purpose Logistics Module Raffaello installed in payload bay of the shuttle. Normally, the MPLM was used to deliver large components and devices for expansion and equipping of the International Space Station. This time, however, the module was loaded only with bags and containers of supplies.

Other equipment flown aboard the Atlantis orbiter as part of the STS-135 mission included: Robotic Refuelling Mission (RRM) – designed to demonstrate technology and tools to refuel satellites in orbit using robotic means; Picosatellite Solar Cell Testbed 2 (PSSC-2) – a miniaturised satellite successfully launched on day 13 of the mission, which became the 180th and final payload launched into Earth orbit by the Space Shuttle; and finally TriDAR – a dual-sensing 3D laser camera designed as an autonomous rendezvous and docking sensor for the ISS.

In addition, thanks to the Lightweight Multi-Purpose Carrier (LMC), it was possible to take the damaged Pump Module from the station’s External Thermal Cooling System back to Earth for examination. Because the crew of the STS-135 consisted of only four people it was possible to load additional material, including experiments in the middeck compartment of the Atlantis orbiter, to bring it back to Earth.

The last flight of space shuttle Atlantis began on 8th July 2011 at 11:29 EDT (15:29 UTC), when the spacecraft lifted off from launch site LC-39A at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

Apart from the fact that, at T-31 seconds before liftoff, the countdown was halted due to lack of an indication that the Gaseous Oxygen Vent Arm had retracted and properly latched (the launch team quickly ensured that all was OK and the countdown resumed less than 2 minutes and 18 seconds later), the STS-135 mission proceeded without problems.

During their nine days aboard the International Space Station, the Atlantis shuttle crew spent most of their time transferring cargo and helping the other ISS crew members from Expedition 28 with maintenance tasks.

Fourteen days after liftoff, space shuttle Atlantis with the STS-135 mission crew returned safely to Earth, landing on runway 15 of the Shuttle Landing Facility at KSC. It was 21st July 2011, 5:57 a.m. EDT (09:57 a.m. UTC), when the space shuttle era officially came to the end.

In addition to the fact that STS-135 was the last space shuttle mission ever flown, it marked several achievements that should definitely be mentioned here. They were: 3rd shuttle flight in 2011; 20th night landing at KSC; 22nd shuttle mission after the Columbia disaster; 26th night landing of a shuttle; 33rd flight of the Atlantis; 37th and last shuttle mission to the ISS; 78th shuttle landing at KSC; 100th day launch; 110th shuttle mission after the Challenger disaster; 133rd shuttle landing overall; 135th shuttle mission since STS-1; 166th NASA crewed space flight. Moreover, a total of 156 astronauts flew with the Atlantis within its 33 missions.

After decommissioning, the space shuttle Atlantis – just like the Discovery and the Endeavour, as well as the test orbiter Enterprise – became a part of a museum collection and can be seen on display.

Following the end of the Space Shuttle programme, there was a nine-year hiatus in NASA manned space flights. It lasted until May 2020, when private space company SpaceX, in collaboration with NASA, once again flew astronauts into orbit and the ISS on a Demo-2 mission, aboard Crew Dragon capsule on a Falcon 9 rocket.

In conclusion, it must be said that NASA is currently working on Space Launch System rocket and Orion capsule – both being considered a direct successor to the Space Shuttle programme. However, the SLS and Orion still have a long way to go in terms of work and testing before manned flights on this rocket can begin. Meanwhile, SpaceX is currently launching people into space and already has several successful missions of this type on its account. And considering the rapid development of other private space companies and commercial space ventures, the future of manned spaceflight seems to belong to them.

Cover photo: The Final Launch of STS-135 Atlantis, NASA, STS135-S-090.

All photos © and credit – National Aeronautics and Space Administration Sources – NASA official releases and press materials were used.