Space stations… The very first attempt of mankind to create a space habitat. Our dream to establish an orbital station allowing humans to stay in space for a longer period of time began to take shape in 1970s, with the early monolithic ´Salyut´ and Skylab spacecraft. However, talking about the real ´home in space´ is possible only with introduction of the first modular habitats – the pioneering Soviet (and then Russian) ´Mir´ space station and its successor, the International Space Station, that is currently orbiting our planet.

Without any doubts, the beginning of the year is permanently assigned to the ´Mir´ station – its first module was launched in February of 1986. The first months of the year also remind us about several records – and also the milestones of space exploration – that were set by the ´Mir´ crews, and finally, the station was deorbited in March of 2001. Therefore, we have decided to introduce you its interesting history.

The beginnings

Political and ideological tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, that began shortly after the World War II, have triggered an economical and technological competition between those two world powers and their allies. Space exploration was one of the most important areas of such rivalry, being observed by the whole world and commonly called a ´space race´.

Both the US and the USSR focused their efforts on gaining supremacy in space, trying to surpass the opponent in achieving subsequent milestones in space exploration. Although the race for space was already launched during the war, it became obvious for the whole world on 25th October 1957 with the launch of ´Sputnik 1´, the first artificial satellite of the Earth. The successful series of the Soviet space achievements lasted until 1969, when the United States sent the first manned mission to the Moon and back.

Although many considered this event as a final stage of the space race, it continued for another decades, even if not being so spectacular as in the 1960s. The superpowers were focusing on both exploring the Solar System and extending the time of human stay in space.

In 1970, the Soviet spacecraft ´Venera 7´ successfully landed on the surface of Venus and one year later ´Mars 3´ soft-landed on Mars. However, contact with this spacecraft was lost after the landing. As a result, Mars was officially conquered by the United States, with the successful landing of Viking 1 in 1976. And in 1977, two spacecraft of the Voyager programme were launched – decades later they became the first human-made objects to enter the interstellar space.

Parallelly to exploring the outer space, both the US and the Soviet Union have realized that another crucial factor in the space race is to make it possible for humans to stay in space for a long time. The idea of orbital stations was a natural step, especially that it was already existing in literature and early space exploration studies.

The first space station programmes were launched in the first half of the 1960s, yet at the very beginning phase of the space race and at a time when the Cold War was in full swing. It´s no wonder that – apart from their official research and scientific role – the space stations were also considered as top secret military facilities.

And exactly the earliest developments of orbital stations projects were intended for a military and intelligence purposes. In 1963, the United States Air Force developed a study of the Manned Orbital Laboratory – a military space station, based on the Gemini programme. This project was, however, abandoned in 1969 together with the need of creating a military-only space station.

In 1965, using elements and equipment from the Apollo programme (precisely by redesigning S-IVB – the third stage of the Saturn IB and Saturn V rockets), a fully equipped research space station was created by the NASA. Officially named Skylab, it was launched on 14th May 1973 and was being operated until 11th June 1979.

The first Soviet studies appeared in 1964 and, similarly to the US, they were made in response to the military needs of creating an orbital station for 2-3 people, with possibility to stay in space for a year or two.

In 1967, the ´Almaz´ (Алмаз – English: diamond) programme was approved for development. For the first time, the project was focused on creating a modular orbit station, allowing the crew of three people to spend long time in the space, in relatively comfortable conditions. Certainly, the purpose of ´Almaz´ was strictly military – the crew had to perform reconnaissance, surveillance and other related duties.

Among the planned important features of ´Almaz´ there was a possibility to intercept enemy spacecraft and, on the other hand, to protect the station from being captured or destroyed. Therefore a special ´space guns´ and other armament were developed together with the station itself.

The original ´Almaz´ programme was officially known as the ´orbital manned station (OPS) 11F71´ (орбитальная пилотируемая станция (ОПС) 11Ф71) and having a military codename Sword (Меч). This project was developed by OKB-52 construction bureau led by V. Chelomey and later known also as CKBM – the Central Construction Bureau for Machine Engineering (ЦКБМ – Центральное конструкторское бюро машиностроения).

However in late 1969, when ´Almaz´ project was in full development and taking the real shape, the internal rivalry, intrigues and particular interest of the Soviet authorities and politics came up on stage. Following an idea created by D. Ustinov, then being in charge of the Soviet military and industrial complex, it was decided in the early 1970 that OKB-52 would transfer the existing documentation of 11F71 to CKBEM – the Central Construction Bureau for Experimental Machine Engineering (ЦКБЭМ – Центральное конструкторское бюро экспериментального машиностроения), led by V. Mishin. And within a year and a half, the CKBEM had to build a less complex simple orbit station using the maximum of already existing equipment, instruments and other elements of space programme – officially known as 11F715 (11Ф715) and commonly named DOS – Long-Term Orbital Station (ДОС – Долговременная орбитальная станция).

On 19th April 1971, the DOS-1 (project 121) orbital station, known also as ´Salyut 1´ (Салют-1), was launched and became the first ever space station orbiting the Earth. The next one, DOS-2, followed in 1972, but due to failure of ´Proton-K´ launch rocket it never reached the orbit and fell into the Pacific Ocean.

In the meantime, the CKBM finished its first station within the original ´Almaz´ programme. It was launched on 3rd April 1973 and officially recognized as ´Salyut 2´(Салют-2), although it was intended purely for military purposes. Shortly after reaching the orbit, the decompression of the station was found and it was deorbited in May the same year.

The first space station from the ´Almaz´ project successfully placed in the orbit was launched on 25th June 1974 and became known as ´Salyut 3´(Салют-3) or ´Almaz-2´. There are a very few information about this station, as again it was a top secret military mission – however, the ´Almaz-2´ was the first spacecraft being equipped with the abovementioned ´space gun´.

There were seven ´Salyut´ orbital stations successfully launched between 1971 and 1982, with three of them belonging to the ´Almaz´ programme. The CKBM was working on the more advanced and improved ´Almaz-4´ station when in 1978 – due to low effectiveness and delays in development – it was decided about closing of this separate project of military manned space stations. Nevertheless, Chelomey and his construction team continued with the development of automatized military spacecraft and the first of them, ´Almaz-T2´ or ´Kosmos 1870´, was successfully launched in 1987.

Nevertheless, both DOS and OPS programmes were a significant milestone in space exploration, paving the way for future developments and increasing the ability of humans to spend more time in space. The joint ´Salyut´ and ´Almaz´ projects were essential for creating and testing basic technologies related to the space habitat ideas, such as docking ports, automatic launching and docking procedures, general construction of small orbital outposts and then opening a way to develop more complex, multi-module crewed spacecraft.

Developing the first modular space station

In 1976, NPO Energia (НПО “Энергия”) company issued a first concept of the modernized and improved space station, to be built on basis of DOS-7 and DOS-8, which already were under construction. The most significant change consisted in increasing the number of docking points – from two that ´Salyut´ stations already had, to four and later even to six. They were also strengthened to allow connection with twenty-tonne modules based on TKS spacecraft, previously used to resupply the stations of the ´Salyut´/´Almaz´ programme. The increased number of docking ports created the possibility to add different modules to the core of the station, therefore turning it into a bigger and more sophisticated spacecraft.

This project was warmly welcomed by the Soviet authorities and, after some redevelopments and necessary upgrades, it was officially approved in 1979. A new generation orbital station had to be created by a consortium of more than 100 companies, led by NPO Energia. Regrettably, the number of participating entities, their supervising organizations, ministries and departments created an unnecessary chaos and complexity. As a result, shortly thereafter the developing structure was redesigned and the project itself was simplified. The NPO Energia and the Salyut construction bureau (КБ “Салют”) were the leading entities and the whole project was coordinated from the operational side by Deputy General Designer Y. Semenov. In 1982-1983, the documentation of the core unit and its systems was ready – and the ´Mir´ space station was officially born.

At this point it is worth to say a few words about the name of the station, as the word ´мир´ has several different meanings in Russian language. First of all, there are both ´peace´ and ´world´, the latter also extended into ´universe´ or ´planet´. And there is also an interesting historical context, because the term ´мир´ was also used to describe a special kind of a rural community, where the land ownership was vested to the community, not to the individual persons (see ´obshchina´ for more information).

However, after the promising beginning, the space race nearly claimed yet another ´victim´, due to ´Buran´ space shuttle programme, that was consuming both financial and development resources.

Launched in 1975, the ´Buran´ programme had to be an answer to the American space shuttle Columbia. Similarly to the Apollo project – that was announced as a ´national programme´ by J. F. Kennedy – the space shuttle development was declared to be just as prestigious by R. Nixon. Being already surpassed in the ´Moon race´, the Soviet Union could not lose face in front of the whole world and desperately wanted to keep pace with the United States.

As a result, the ´Mir´ programme was frozen in 1984 and all resources were targeted on the ´Buran´ project. Fortunately, there were still a few people within the Soviet authorities that considered the space station programme as an important opportunity in their political career, including the Minister of General Machine Building O. Baklanov and the Military Industry Secretary G. Romanov. Therefore, completing the ´Mir´ orbital station became a political matter and had to be done until 25th February 1986, the date of 27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

It was clear that, according to the original development schedule, it would be impossible to meet the new deadline and launch even the first, base module of the ´Mir´ until the given time. Therefore, the work had to be speeded up and therefore, on 12th April 1985, a model of the base block was sent to Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan for testing the station systems. It should be mentioned here that the ´Mir´ was equipped in several modern complexes, being either already proven in other space missions or newly designed for this station. They included ´Salyut 5B´ digital flight control computer and gyrodyne flywheels (the same as in ´Almaz´ stations), ´Kurs´ automatic rendezvous system, ´Luch´ satellite communication and life support systems – ´Elektron´ oxygen generators and ´Vozdukh´ carbon dioxide scrubbers.

In early 1986, the DOS-17K (DOS-7) was ready to be lifted-off into space. Initially, the launch was scheduled for 16th February but it had to be postponed due to problems with communication system. Finally, on 19th February 1986 at 21:28:23 UTC – even a few days before the official deadline – a ´Proton-K´ rocket carrying the DOS-7 successfully launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and shortly afterwards reached the Earth´s orbit and placed the module there.

Over the next ten years, the base block of the station will be enhanced with six other modules, therefore adding a new milestone to the space exploration timeline – creating the first ever modular space station.

The first human-made space habitat

The base block of the ´Mir´ station consisted of a spherical docking module and a stepped-cylinder-shaped main compartment, both separated by an airlock. Main facilities of the latter included primary living quarters for the crew, life support systems, main engines and altitude control systems.

The first crew of Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov arrived to the station on 15th March 1986, on board of ´Soyuz T-15´ spacecraft. An interesting fact is, that their mission was the only one when crew stayed at two different space stations. Before reaching the ´Mir´, Kizim and Solovyov spent 50 days on board of ´Salyut 7´, to dismantle some of the equipment that was later to be used on the ´Mir´. On 16th July 1986, they have returned to the Earth and the ´Mir´ remained uninhabited for the six following months.

And only with the arrival of Yuri Romanenko and Aleksandr Laveykin in February 1987, the period of permanent human presence and work in the space habitat began. It lasted until 2000, apart from a four-month break between April and September 1989, caused by technical problems with ´Soyuz´ spacecraft.

It must be pointed that although the ´Mir´ station was emphasizing the milestones of the space exploration achieved by the Soviet Union and at the same time proving the importance of its space industry, it later became also a symbol of reconciliation between East and West, as well as of international technological and scientific cooperation between the USA, the Soviet Union and other countries of the world.

During ten years of its operation, the first modular space station was visited by many non-Soviet astronauts. The first of them, Muhammed Faris from Syria, arrived yet in July 1987. Within the next year, the ´Mir´ station was visited by cosmonauts from Afghanistan, Bulgaria and France.

In 1990, the first ´Kosmoreporter´ – a Japanese journalist Toyohiro Akiyama – visited the station and spent seven days aboard. Then there were four other French astronauts, four Germans, and one per Slovakia, Austria, UK and Canada.

Nevertheles, the second largest national group that visited the ´Mir´ station were Americans. The first of them was NASA astronaut Norman Thagard, who spent 115 days onboard the station in 1995. Thagard, being already a veteran of four space flights, participated in the ´Mir-18´ mission and became the first American ever to travel to space on board of the Russian spacecraft and therefore the first American cosmonaut.

American presence at the ´Mir´ was a direct result of the ´Shuttle – Mir´ programme, which ultimately had a very large impact on the expansion and future of the station. Thus, it is worth mentioning its history and origins – but, in order to do this, we have to look back into the mid-1970s.

The beginnings of Soviet-American cooperation dates back to 1975, when – despite the Cold War being in full swing – the United States and the Soviet Union conducted the first manned international space mission, known as the ´Apollo – Soyuz´ Test Project. As part of that mission, the successful docking of the Apollo module to the ´Soyuz´ space capsule was performed. Additionally, after the docking, the American astronauts and the Soviet cosmonauts together conducted several scientific experiments in space.

The next step of this bi-national cooperation had to be a ´Shuttle – Salyut´ programme, planned for the 1970s and 1980s, but regrettably, this idea was never realised.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and then deteriorating economic and financial situation of the newly established Russian Federation, placed a question mark over the future existence of the ´Mir´ station and other Russian space programmes. In this situation, a reasonable solution to sustain these programmes was to establish international cooperation.

On 17th June 1992, the US President George Bush and the President of Russia Boris Yeltsin signed an ´Agreement between the United States of America and the Russian Federation Concerning Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for Peaceful Purposes´. One of the consequences of this agreement was the already mentioned ´Shuttle – Mir´ programme, that was officially announced in 1993.

This programme allowed Russian cosmonauts to fly to the ´Mir´ station on board of American space shuttles in order to carry out joint long-term expeditions there and to conduct scientific research together aboard the station. In return, the Americans could draw upon the Russian knowledge and experience in long-term human spaceflights, which was considered the first step towards creating a new, common orbital station, later known as the International Space Station.

On 3rd February 1994, Discovery space shuttle was launched from the Kennedy Space Center and became the first NASA spacecraft that flew to the ´Mir´ station. Its crew consisted of five Americans and a cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, who became the first Russian being lifted off into space onboard of a space shuttle.

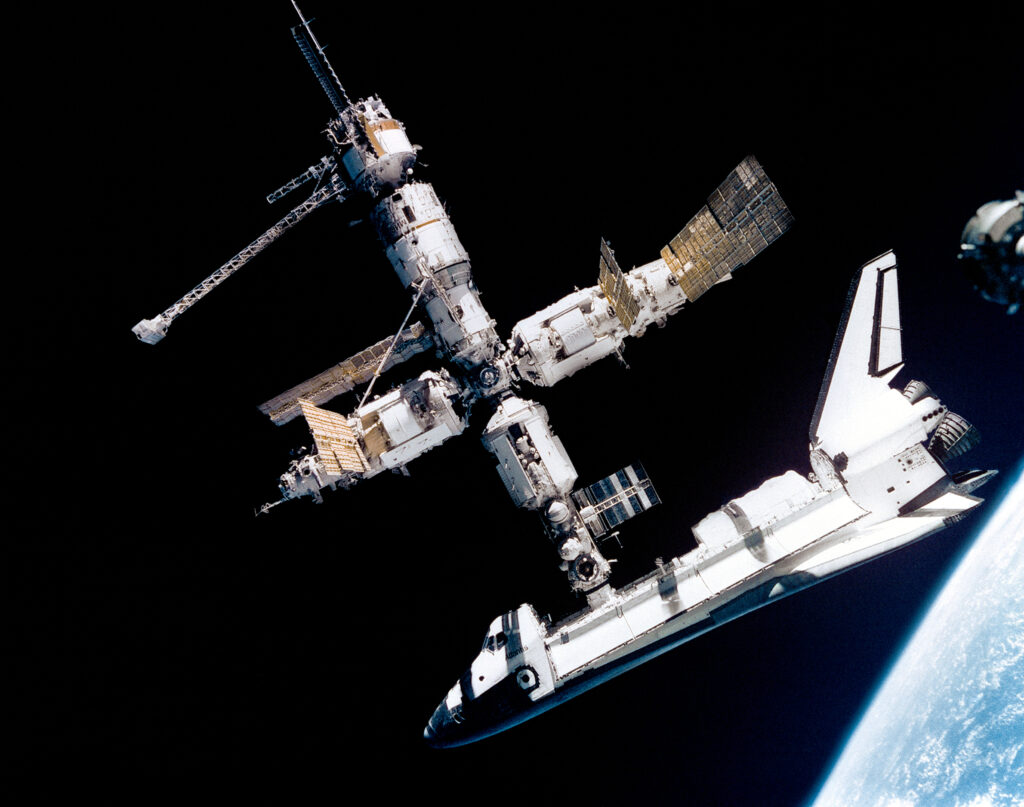

The ´Shuttle – Mir´ programme was continued within the next four years, until 1998. During this time, the NASA space shuttles made eleven flights to the ´Mir´ and nine of them docked to the station – ´Atlantis´ seven times, while Discovery and Endeavour each docked once. The American astronauts participated in seven expeditions and spent approximately 1,000 days in space onboard the ´Mir´ station. Within the programme, the space shuttles delivered a total of 53 people to the station (44 Americans, 6 Russians, 2 French and 1 Canadian) and also some scientific equipment.

Alongside the space shuttles, the ´Soyuz´ spacecraft was used for flying to the ´Mir´ station. The Russian spacecraft performed thirty missions, delivering there a total of 56 cosmonauts (36 from Russian and 18 from other countries). Supplies, fuel and spare parts delivery were secured by another Russian-made, unmanned cargo spacecraft of ´Progress´ series.

Scientific modules of the ´Mir´ station

The bi-national cooperation of two superpowers did not only allowed to maintain a human presence aboard the station but also had a direct influence on the development of the ´Mir´ shape and abilities. Finally, the station consisted of as many as seven modules and its overall expansion lasted ten years. This period can be divided into two main stages, separated by a five-year break due to the fall of the Soviet Union and its consequences. But let´s start from the beginning…

Expansion of the station began just over a year after its base module was deployed in space. The first of the ´Mir´ extension modules, named ´Kvant-1´, was launched on 31st March 1987 and docked to the core module on 9th April. It was an astrophysics module, allowing to conduct research in this area and additionally worked as the main docking port for ´Progress´ spaceships.

Then an augmentation block called ´Kvant-2´ was added. It arrived the station on 6th December 1989 and was primarily used for Earth observation and biotechnology experiments. This module was also a base for Extra Vehicular Activities at the ´Mir´.

On 10th June 1990 another module was added, a technology block known as ´Kristal´ or ´Kvant-3´. It was mainly used for experiments involving heat processing of various materials, as well as biotechnology research and astronomical observations. It is worth to mention that this module was equipped with two additional berthing ports, which were planned to be used in the future for docking the ´Buran´ space shuttle. However, due to the failure of the programme associated with this type of spacecraft, the merger of the Russian shuttle with the ´Mir´ station has never happened.

The ´Kristal´ module was the last addition to the station performed before the final collapse of the Soviet Union. Fortunately, thanks to the above mentioned bilateral agreement on space exploration, the station was not only saved and thus could proceed with manned missions onboard, but it was also decided that the USA would fully fund and equip further scientific modules for the ´Mir´.

Operational use of the American space shuttles in flights to the ´Mir´, required a rearrangement of the existing station modules, particularly in relocating the ´Kristal´ to a bottom node of the docking adapter. This provided enough clearance between the station solar arrays and the space shuttle to be docked with the ´Mir´. Shortly afterwards, on 20th May 1995, the Atlantis shuttle was launched, carrying the first NASA-founded module for the station, named ´Spektr´. The scientific equipment of the ´Spektr´ block allowed to conduct a research on the Earth´s atmosphere, geophysical processes and cosmic radiation. In addition, it was also the living compartment for American astronauts and served as a power module for the station.

In November of the same year, the Atlantis was launched again, this time with a special Docking Module for the ´Mir´. This element was designed to facilitate berthing of the space shuttles to the station and used a modified version of the Androgynous Peripheral Attach System, originally intended for the Soyuz-Apollo project.

The final module attached to the ´Mir´ was delivered in April 1996 by the ´Proton-K´ rocket, launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. It was an Earth-sensing module named ´Priroda´, founded by the NASA, and with the objective of conducting experiments on Earth´s resources, using a remote sensing. In order to carry out such research, a large synthetic radar antenna was mounted outside the module. Although being NASA-founded, the ´Priroda´ performed experiments provided by twelve different countries.

When the ´Priroda´ module was added, the station expansion process was completed. The ´Mir´ remained in such configuration until the end of its operation.

A record-breaking milestone in the space exploration

The ´Mir´ station was not only the first modular orbital station and the first human-made space habitat, but also the biggest spacecraft and in general the biggest human-made object in space. The DOS-7 and ´Kvant-1´ modules, with Soyuz-TM and Progress M spacecraft docked to them, were 33 metres long. The ´Priroda´, ´Kristal´ and docking compartments were, in turn, 31 metres wide. And finally, the ´Spektr´ and ´Kvant-2´ blocks, together, were 27.5 metres of height.

Eventually, the station consisted of seven modules and several unpressurised components with solar arrays and various devices mounted on them, and yet increasing its overall size. The in-orbit mass of the station was, depending on sources, between 124.5 and 140 tonnes. Nevertheless, the size and weight were just first, but not the only space exploration records, related to the ´Mir´ station.

First of them was that the ´Mir´ has been orbiting the Earth for fifteen years, basically three times its initially planned lifetime. And it was inhabited by humans for twelve and a half years, therefore setting a record for the longest continuous human presence in space at a total of 3,644 days. During that time, a total of 104 people visited and lived aboard the station.

One of the basic reasons of launching the ´Mir´ into space was to provide a research on long-lasting human stay in space, being a first step into the long-distance space travelling. Several cosmonauts spent more than one hundred days inside the station, with an absolute record set by Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov who inhabited the ´Mir´ for exactly 365 days 22 hours and 38 minutes. It was the very first time a human spent more than a year into space.

An absolute, still unbroken, record of the single longest stay in space was also set thanks to the ´Mir´ station. This record is held by Valery Polyakov who flew to the orbital station on 8th January 1994 and returned on 22nd March 1995 – after an incredible stay in space for 437 days and 18 hours.

Nevertheless, even such a breath-taking record of the longest single stay is space did not secure Polyakov the title of cosmonaut that overall spent the longest period onboard the ´Mir´ station. This achievement belongs to Sergei Avdeyev, who, combining three visits to the station, spent there a total of 747 days, 14 hours, 12 minutes and 27 seconds (27th July 1992 – 1st February 1993, 3rd September 1995 – 29th February 1996, 13th August 1998 – 28th August 1999). In addition, those numbers include 41 hours spent in open space during Extravehicular Activities (EVA) and 59 minutes in decompressed environment.

Furthermore, the NASA astronaut Shannon Lucid – who flew to the station on 22th March 1996 and returned on Earth after spending 188 days and 4 hours in space – holds records in three categories: the longest time spent in space by a woman, the longest spaceflight endurance by an American and the longest time spent in orbit by a non-Russian cosmonaut.

Apart from the above mentioned records, an interesting fact is related to two other cosmonauts – Alexandr Volkov and Sergei Krikalev – who also spent a long time aboard the ´Mir´, although it was not actually planned. For the first time, they flew together to the station on the turn of 1988 and 1989; and spent 151 days there. The second Krikalev´s mission to the ´Mir´ station began on 18th May 1991 and after approximately five months he was expected to return on the Earth.

However, in July he agreed to extend his stay in space and wait at the station for Soyuz TM-13 crew, that arrived in October. Unfortunately for Krikalev, the mission engineer who arrived with TM-13 flight, was not trained for long-duration space flight and returned on the Earth after eight days at the ´Mir´. The two cosmonauts that stayed at the station were Krikalev and Volkov, the latter being the commander of TM-13 crew who decided to stay in space with his colleague.

And then, on 26th December 1991, while both Krikalev and Volkov were still onboard the ´Mir´ station, the country that sent them into space ceased to exist – the Soviet Union was officially dissolved. This caused a lot of tension and uncertainty about their return to the Earth. Fortunately, all issues were finally solved early next year and both cosmonauts left the station on 25th March 1992. They successfully landed in now independent Republic of Kazakhstan and are often being referred as ´the last citizens of the Soviet Union´. This unexpectedly extended mission lasted 175 days for Volkov and 311 days, 20 hours and 1 minute for Krikalev (instead of approximately 150 days as initially planned).

Nevertheless, the issue with their return on the Earth in 1992 did not deter Krikalev from further flights. He later successfully accomplished another four space missions, two of which were the long-duration flights (140 and 179 days in space).

Finally, two other interesting events related to the ´Mir´ station should be also mentioned. First of them are the spacewalks performed on 1st and 5th February 1990 by Aleksandr Viktorenko and Aleksandr Serebrov. During those Extravehicular Activities the cosmonauts were testing a 21KS personal manoeuvring unit, a device similar to MMU developed by the NASA and tested in 1984.

Viktorenko and Serebov spacewalked up to 45 meters away from the station, however – unlike the American astronauts testing the MMU – they remained connected with the station by a tether, for security reasons. Although the tests were successful, the 21KS manoeuvring unit were retired after this mission, suffering the same fate as the mentioned MMU.

The EVAs were performed at the ´Mir´ station using several consecutive variants of ´Orlan´ (Орлан – English: sea eagle) space suit. Its roots date back to the times of the Soviet manned lunar programme and the ´Orlan-D´ variant was tested in the open space for the first time in 1977.

During the ´Mir´ expeditions, two upgraded variants of the space suit were used – ´Orlan-DMA´ (since 1988) and ´Orlan-M´ (1997). They also are related with some space exploration milestones like a spacewalk performed by the NASA astronaut Jerry Linenger in 1997. He then became the first American to perform a spacewalk from a foreign spacecraft and, at the same time, using a non-American made suit. And speaking of Linenger, he also holds a record of the longest duration flight of an American male, as he spent 132 days, 4 hours and 1 minute in space during his mission onboard the ´Mir´.

Experiencing a rough time

In its history, the ´Mir´ station had witnessed not only the lights but also some shadows of the space exploration. Many of them were a really thrilling events, but fortunately all issues were solved without any casualties.

The first serious accident occurred on 6th September 1988, although it was not directly related with the station itself. On this day, when cosmonauts were returning to Earth aboard ´Soyuz TM-5´ spacecraft, a combination of several human errors and system failures put them into a dangerous situation without possibility to perform a deorbit manoeuvre. Fortunately, after spending 24 hours in the orbiting re-entry capsule, the crew managed to return safely on Earth.

In 1990, shortly after launching ´Soyuz TM-9´ into space, its crew noticed a problem with thermal protection sheets on their re-entry module. On 17th June, after docking the station, cosmonauts Anatoly Soloviev and Alexander Balandin repaired the sheets during a spacewalk. However, they encountered problems with closing the airlock hatch in the ´Kvant-2´ module. Fortunately, the station crew managed to depressurize the middle compartment of the module and use it as an emergency airlock. The cosmonauts safely returned to the station and repaired the faulty hatch during their next EVA on 25th July.

On 14th January 1994, while performing an overflight inspection of the station before returning on Earth, the crew of ´Soyuz TM-17´ has lost control over the spacecraft and bounced off the ´Kristal´ module a few times. Fortunately, neither the ´Soyuz´ nor the ´Mir´ suffered serious damage and could continue with their missions. Later it was found that the ´Soyuz´ crew exceeded the maximum weight allowance of their spacecraft that most probably was a direct cause of this collision.

23rd February 1997 marked one of the most dramatic days in the history of the ´Mir´ space station. On that day, its crew faced one of the worst dangers one can encounter while being on a spacecraft – during replacing a fuel cartridge of solid fuel oxygen generator in the ´Kvant-1´ module, a malfunction occurred and fire broke out at the station.

The fuel cartridge is commonly known as ´oxygen candle´ – it consists of a chemical mixture with iron particles. When it burns, the oxygen is being released. However, this time something went wrong and an open fire appeared.

The whole interior of the station was filled with smoke, forcing the crew to use oxygen masks. Unfortunately, due to space limitation in the ´Kvant-1´ module, the fire could be directly extinguished by only one person. It was the crew commander Valery Korzun who tried to put the fire out, while the others were handing him fire extinguishers. The fire lasted about 15 minutes and the ´Vika´ generator and its oxygen container were almost completely burnt down. Thankfully, the station was not seriously damaged nor was anyone of the crew injured.

After nearly two years of investigation it was stated that the fire was caused by a piece of latex, coming from a glove used while replacing the fuel cartridges in the generator. It was the largest and most serious incident of that kind that ever happened on board of a manned spacecraft.

An incident that occurred on 3rd March 1997 almost resulted in an orbital collision. On that day, a test-docking of ´Progress M-33´ cargo ship was scheduled, through so-called TORU system (Телеоператорный Режим Управления / Teleoperated Mode of Control). It was the manual docking procedure, working as a backup for the ´Kurs´ automatic rendezvous system.

After a successful undocking of the ´Progress M-33´ on 6th February, an attempt to re-dock using BPS-TORU procedure (БПС – баллистическое прецизионное сближение / Ballistic Precision Rendezvous) failed due to loss of video image and had to be aborted. Nevertheless, the cargo spacecraft passed by the space station, within a distance of only a few metres.

Just a few months later, the ´Mir´ station was involved in the most severe collision in the history of space flights – and again it was caused by malfunction of the TORU system. On 24th June 1997, the ´Progress M-34´ cargo spacecraft undocked the station and returned to to it one day later, to perform another test-docking through the BPS-TORU.

And once again, the ´Mir´ crew have lost control over the ´Progress´, however, with even more serious consequences. The M-34 cargo spacecraft collided with the station, damaging some of its solar panels and the ´Spektr´ module, causing its depressurization.

As a direct result of this collision, the ´Mir´ station started to drift, but fortunately the crew managed to stop that, using the ´Soyuz TM-26´ spacecraft docked to the station. Nevertheless, the remaining solar panels generated approximately one-third less energy than before, causing a power shortage at the station.

The crew has engaged their efforts to assess the damage, repair some of the systems and restore power capacity. It was performed during an Intra-Vehicular Activity (IVA) inside the module (by commander Anatoly Solovyev and crew engineer Pavel Vinogradov) and next, throughout an additional six-hour spacewalk outside the station (Solovyev and American astronaut Michael Foale). However, the ´Spektr´ module remained permanently excluded from use, until the end of the station operation.

Apart from the abovementioned problems that the station and her crews faced over the years, there were – unfortunately – many other more or less serious malfunctions onboard the ´Mir´. Their number was increasing in time, being a result of normal wear and tear of the station components.

Those problems, and especially the mentioned fire from February 1997, led to fears that further staying in the station may endanger the crews and caused some tensions between the NASA and the Russian Space Agency (Роскосмос – Roskosmos).

It was, in fact, the beginning of the end for the ´Mir´ station. The tensions mentioned above, ageing of the station and also lack of funds for keeping it operational, caused that on 2nd July 1998, the General Director of Roskosmos Yuri Koptev made a decision about deorbiting the first human-made modular space station. Initially, its deorbit procedure was planned for June 1999.

One of reasons that have sealed the fate of the ´Mir´ station was the beginning of another step in Russian-American partnership in exploration of space. It was officially marked on 20th November 1998 by launching of ´Zarya´ (Заря – English: dawn) – also known as the Functional Cargo Block and being the first module of the new space station, that later became recognized as the International Space Station (ISS).

With the beginning of the ISS programme all resources of the Roskosmos were focused on supporting development and creation of the new space station, leaving nothing for keeping the ´Mir´ in operational condition.

The final gasps

Although the decision was already made, two next manned flights to the ´Mir´ were performed in August 1998 (cosmonauts Padalka and Avdeyev) and in February 1999 (cosmonauts Afanasyev, Ivan Bella – the first Slovak in space and French spationaut Jean-Pierre Haigneré).

The mission from February 1999 was the last official flight to the ´Mir´ station. As two seats in the ´Soyuz TM-29´ spacecraft were sold to Slovakia and France, Avdeyev had to extend his stay on board the ´Mir´ – on 27th February Padalka and Bella returned to Earth and the station was inhabited by its last crew: Afanasyev, Avdeyev and Haigneré.

They proceeded with preparing the station for deorbiting procedure. A special analogue computer was mounted for this purpose, the cosmonauts also sealed off each of the spacecraft modules. Apart from those tasks, they also performed yet another several scientific experiments and three spacewalks. On 28th August 1999, the last official crew of the ´Mir´ space programme left the station and returned on Earth.

This marked the end of almost ten-year-period of continuous human presence aboard the station. A little over a week after that, on 7th September 1999, the main computer and gyroscopes (gyrodynes) of the ´Mir´ were switched off. Being already ´dead´ and unactive, the space station was since then controlled only by the ´Progress M-42´ spacecraft docked to it.

Nevertheless, on 7th June 1999, yet while the last ´Mir´ crew was still at the station, the Russian space authorities have announced that the station deorbiting would be delayed by six months. It was then still believed that the ´Mir´, despite the age of its particular modules, did not lost its potential and could stay in space yet for a few more years.

When the delay in deorbiting was announced, a desperate search for funds began. Among the ideas how to extend the operational life of the ´Mir´ station was to privatize it and then turn into the first in-space TV and movie studio, or even use it for space tourism purposes.

This led to creation of MirCorp – a private company focused on reactivation and further operation of the station. It was established by Walter Anderson, an American multi-millionaire telecommunication entrepreneur, philanthropist, investor and space enthusiast, who became the main investor of the company.

Seven months after establishing the MirCorp, on 4th April 2000, the first privately-funded space mission began. Cosmonauts Sergei Zalyotin and Aleksandr Kaleri arrived the ´Mir´ onboard ´Soyuz TM-30´ spacecraft and spent two months at the station to perform necessary repairs. Another manned flight was already scheduled, with the crew of cosmonauts Salizhan Sharipov and Pavel Vinogradov, however the lack of funds forced the MirCorp to abandon this idea.

As a result, Zalyotin and Kaleri left the station on 15th June 2000, leaving it uninhabited. In fact, they were the last humans onboard the ´Mir´. Shortly afterwards, due to insufficient budget, the MirCorp ceased its activities.

Nevertheless, the final manned mission to the ´Mir´ managed to increase the number of space exploration milestones related to that station. The flight of the ´Soyuz TM-30´ was, as already mentioned, the first privately-funded space mission ever. Using of the ´Progress M-1´ cargo ship to deliver supplies for Zalyotin and Kaleri resulted in the first privately-funded mission of unmanned space vehicle. And, because the cosmonauts performed the EVA, this mission was also the first with privately-funded Extra-Vehicular Activity.

Finally, following the initial announcement of the Russian authorities and further actions performed by the MirCorp, the deorbiting of the station was delayed until 2001.

Earth to Earth

However, in the middle of 2000, the final fate of the ´Mir´ space station was still open. The Russian authorities were arguing each other, with the Roskosmos believing that – despite of transferring the funds for the ISS projects – there is yet a way to save the station and keep it operational. On the other hand, Koptev´s position as the General Director of the Russian Space Agency was compromised.

Eventually, on 30th December 2000, the Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov signed a definitive decision on decommissioning the ´Mir´ station. From now on, its deorbit was inevitable. The procedure was finally initiated in January 2001 and was divided into three separate phases.

The first one reduced the orbital altitude of the ´Mir´ station to 220 kilometres. Also at this stage, the station merged with ´Progress M1-5´ spacecraft that had to play an important role in the next stages of the process.

The second stage began on 23rd March, with two burns of control engines of the aforementioned ´Progress´ spaceship being docked to the station. The first burn was performed at 00:32 UTC and the second at 02:01 UTC. As a result, the station was transferred to elliptical, 165 x 220 kilometre, orbit.

The third and final phase, was initiated three hours later, after two laps around the Earth. At 05:08 UTC, the control engines and the main engine of the ´Progress M1-5´ fired for more than 22 minutes, causing the station to enter into the Earth´s atmosphere at 05:44 UTC. Eight minutes later, the first modular orbital station in human history broke into pieces.

Some of it elements, that did not burn up during re-entry, splashed into waters of the South Pacific Ocean, about 3,000 kilometres off the coast of New Zealand.

And that was the ´Mir´ station

Initially, the ´Mir´ orbital station was supposed to be the ultimate symbol of the Soviet Union´s superiority in space. However, the change of political situation and the end of the Cold War turned it into a symbol of international reconciliation in the name of a common purpose of understanding and exploration of space.

During the fifteen years of its operation, more than 23,000 of experiments and scientific research were carried out aboard the station, significantly improving our knowledge and understanding of the universe and its nature. More than 1,7 TB of scientific data were transferred from the ´Mir´ to Earth.

The manned expeditions to the station and all those years of continuous human presence onboard the ´Mir´ have proved to be invaluable in understanding of human body behaviour during prolonged stay in microgravity conditions. This was our first step to be ready to think about the long-distance and long-endurance space travels.

All the experience gained during designing, constructing and operating the ´Mir´ station – including also all the malfunctions and incidents that occurred up there – has contributed directly to creation of its successor, the International Space Station, which is currently orbiting above our heads.

The station was visited with a total of 28 long-duration crews, each of them lasting six months on the average. The ´Mir´ was visited by 104 people from 12 different nations, thirty-five astronauts and cosmonauts performed a spacewalk.

Finally, it should be mentioned about a symbolic accent connecting both the ´Mir´ and the ISS stations, that emphasizes their common roots. The DOS-8 module – mentioned at the beginning of this story and being initially a backup module for the DOS-7, the core module of the ´Mir´ station – finally become the third mayor module of the International Space Station, officially named ´Zvezda´ (Звезда – English: star).

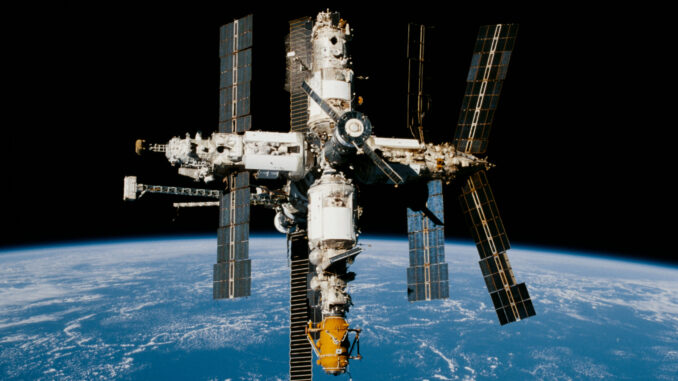

Cover photo © NASA: STS089-346-007 (22-31 Jan 1998) — After several days of joint activities between NASA astronauts and Russian cosmonauts in Earth-orbit, the Space Shuttle Endeavour’s crew recorded a series of 35mm and 70mm ‘flyaround’ survey photos of Russia’s Mir Space Station. Earth’s horizon serves as the backdrop for this 35mm scene.