In the beginning of November 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War in the Northern Africa, Italian lieutenant Giulio Gavotti dropped four grenades from his Taube aeroplane on Turkish positions at Ain Zara and Tagiura oasis. That event is usually recognized as the first reported aerial bombing from heavier-than-air aircraft.

In the beginning of November 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War in the Northern Africa, Italian lieutenant Giulio Gavotti dropped four grenades from his Taube aeroplane on Turkish positions at Ain Zara and Tagiura oasis. That event is usually recognized as the first reported aerial bombing from heavier-than-air aircraft.

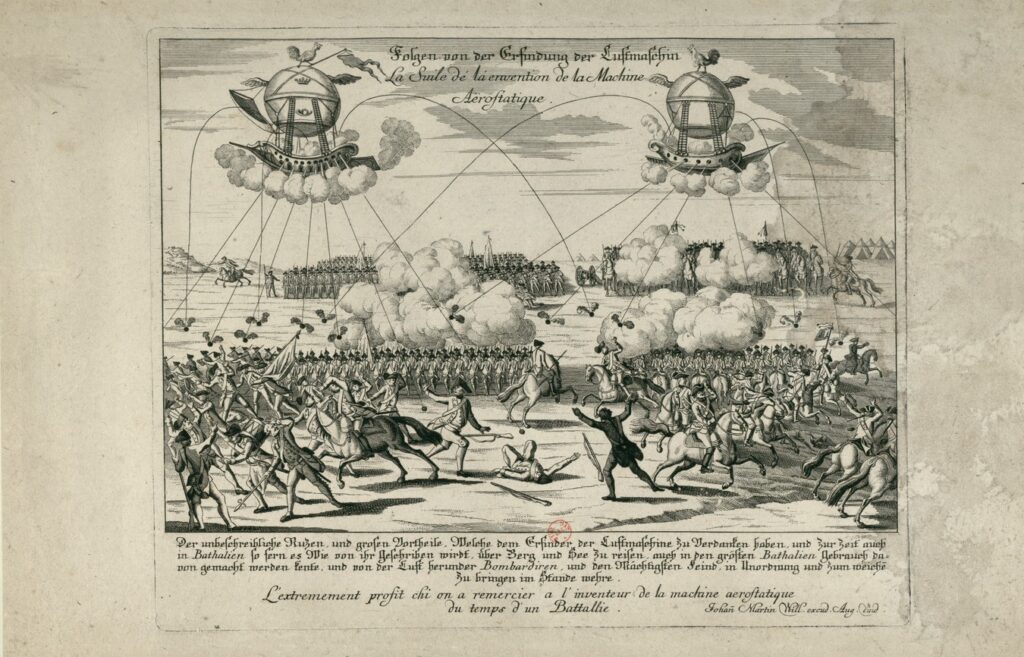

The idea of using aircraft in combat to drop incendiary or explosive charges on enemy´s hinterland is as old as aviation itself. Already in 1792, during the French Revolutionary Wars, one of the Montgolfier brothers – approximately just a decade after the first successful flights of their hot air balloons – proposed to use an aerostat to drop bombs on British forces in Toulon.

In 1807, another attempt to bomb British ships was made in Denmark, this time with hand-propelled dirigible. Then, other proposals to use balloons for dropping explosives on enemy forces were formed in the Great Britain and the USA. However, all of them remained just the ideas that never have been brought to life.

The first use of aircraft in combat dates to July of 1849. During the First Italian War of Independence, the Austrian forces performed an action that nowadays we could call a bomb raid. Approximately two hundred hot air balloons made of paper were sent over Venice, each of them carrying 25-30 pounds (12 to 14 kgs) of explosives with a time fuse. An interesting fact is that the balloons were launched from both land and sea – the Austrian side-wheel steamer SMS Vulcano was used as a balloon carrier and performed the first air raid in the naval history.

However, the Austrian attack had only a psychological significance. Just a few of the launched balloons reached the city and, according to some reports, only one bomb was released. The strong wind caused most of the aircraft missed the target and some were even drifted back to Austrian lines.

Despite the poor result, the Austrian forces proved that using balloons for air raid purposes was technically feasible. During the second part of the 19th century, hot air balloons were used in combat by France, Italy, China and Japan. The threat from the skies became real.

Even more frequent use of balloons to drop explosives on enemy lines, caused the subject of aerial bombing was discussed by the world´s leading powers during the International Peace Conference at the Hague, in 1899. The outcome was that contracting powers agreed to prohibit – for a time of five years – ´the launching of projectiles and explosives from balloons, or by other new methods of a similar nature´. The corresponding declaration was issued on 29th July 1899 and signed by all twenty-five countries participating in the Conference, except the USA.

In 1903, the Wright brothers made their flight of the Wright Flyer, the first aeroplane in history. Shortly after, development of heavier-than-air aircraft rapidly grew and initial attempts to use the aeroplane for military purposes were reported.

The aforementioned prohibition was again discussed during the Second Hague Conference in 1907. It resulted in updated Declaration Prohibiting the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons, which even extended the scope of prohibited activities. That Declaration was to remain in effect until the Third Hague Conference but that was never organized. Therefore, from a legal standpoint, the Declaration is still in force.

Regrettably, the updated Declaration from 1907 was not signed by several world powers, including France, Germany, Japan, Italy and Russia. From the leading world´s countries, the Declaration was signed and ratified by the Great Britain and the United States. It was also signed by Austro-Hungary, but never ratified.

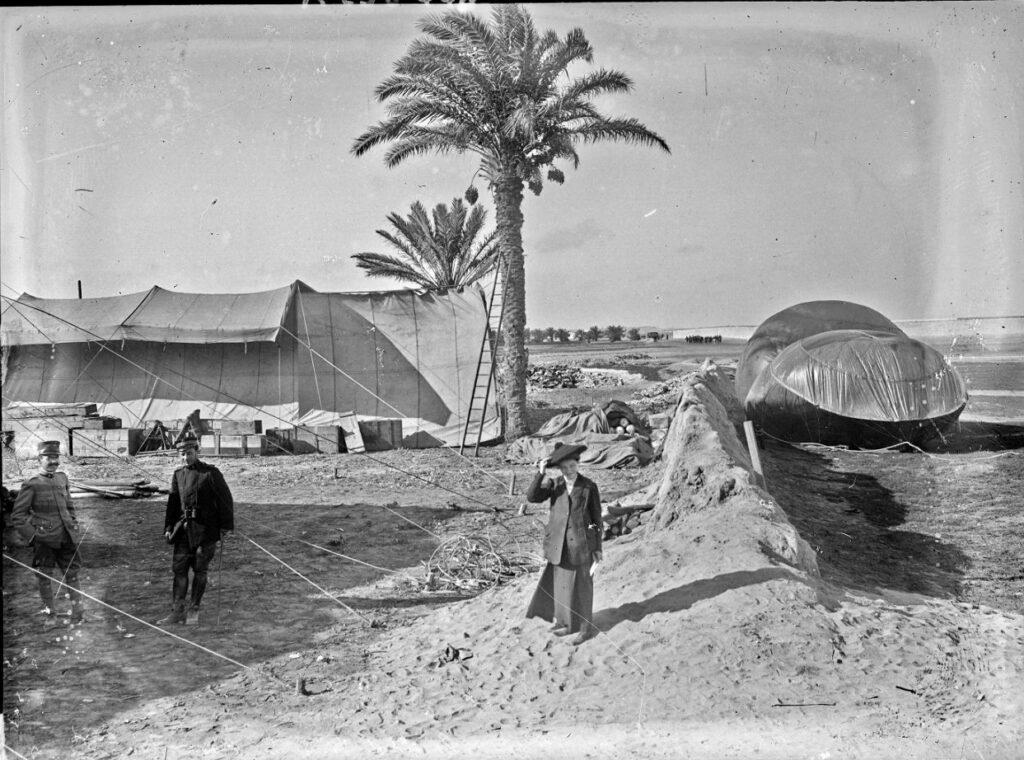

On 29th September 1911, a war between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire broke out. The war gripped areas in the Northern Africa, including territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (of today´s Libya), as well as including Dodecanese islands. A force of approximately 100,000 Italian troops invaded Libya, equipped with the latest technological achievements, such as armoured cars and aeroplanes.

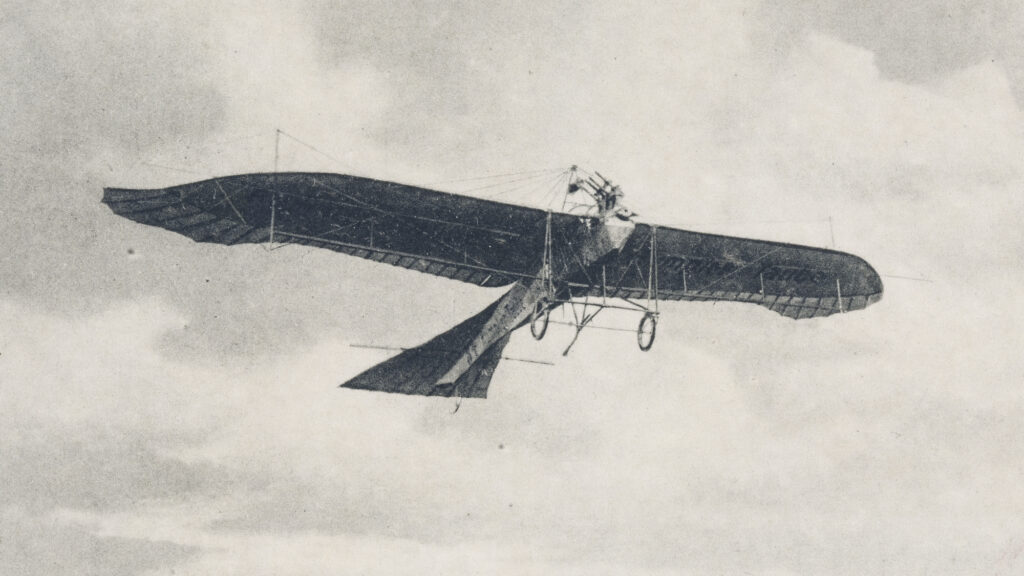

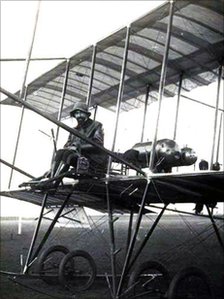

On 23rd October 1911, Captain Carlo Piazza performed the first in history reconnaissance flight with heavier-than-air aircraft. One week later, Lieutenant Giulio Gavotti dropped four bombs on Ottoman positions from his Taube monoplane. The first airstrike from the heavier-than-air aircraft became a reality, just eight years after the invention of an aeroplane.

Although it may seem that Gavotti´s air raid was an example of spontaneity, the first combat use of an aeroplane was planned well in advance and logistically supported. In a letter Giulio Gavotti wrote to his father before the combat, he mentioned the arrival of two boxes with Cipelli-type bombs and expected use of them against enemy positions. In the early 21st century, the letter was made available to the BBC by Gavotti´s grandson and the British broadcaster published extensive quotes from it.

The Italian airstrike made the Ottoman Empire to issue an official protest note, invoking the above mentioned Declaration from 1907 and regardless the fact it was not signed by Italy. A short Italian reply to that note pointed out that the Declaration was mentioning only the balloons, not heavier-than-air aircraft.

Shortly after, the Italian aeroplanes in the Northern Africa performed further airstrikes on the Ottoman positions.

In March of 1912, Giulio Gavotti made the aviation history again by performing the first night combat mission in a heavier-than-air aircraft.

Over the next years, Gavotti remained closely related to development of Italian military aviation. Until his retirement in the late 1920s, Giulio Gavotti was involved in pilots´ training, flight tests of new aeroplanes and aircraft manufacturing. After leaving the air force, he was a board member of two Italian airline companies.

Giulio Gavotti died in Rome, on 6th October 1939, at the age of 56.

Cover photo: Taube-type monoplane (illustrative photo), ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / PK_008631, Public Domain

Sources: publications of the International Committee of the Red Cross; D.Schindler and J.Toman, ´The Laws of Armed Conflicts´ (1988)