Back in the 1920’s, Germany began a rapid development of rocket technology, which began to intensify during the Second World War, mainly due to creation of the V2 ballistic missiles. After the end of the conflict, the US and the USSR took over several German scientists, among them the rocket specialists, to use their knowledge for their own purposes. Post-war political tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union led to their rivalry in the economic and technological fields – including the space conquest. That quickly became one of the most important aspects of contest between the two superpowers. When in October 25th, 1957 – less than twelve years after the end of World War II – the Soviet Union launched the first artificial satellite in the world – Sputnik 1, for both competing countries and for the whole world, it became clear that the next step in this space race would be to send there a man.

Preparations for the first human flight into space on both sides ran in a hurry and under a strong pressure of time. Both the United States and the USSR were aware that their rivals could do that at any time, as the first. In March 1960 in Russia there was a squad of candidates for cosmonauts formed, consisting twelve young officers – all of them being pilots of jet aircraft. In April of the same year, the number of candidates was increased to twenty. In the next step, six candidates were selected from this group for the first flight and Yuri Gagarin was one of them.

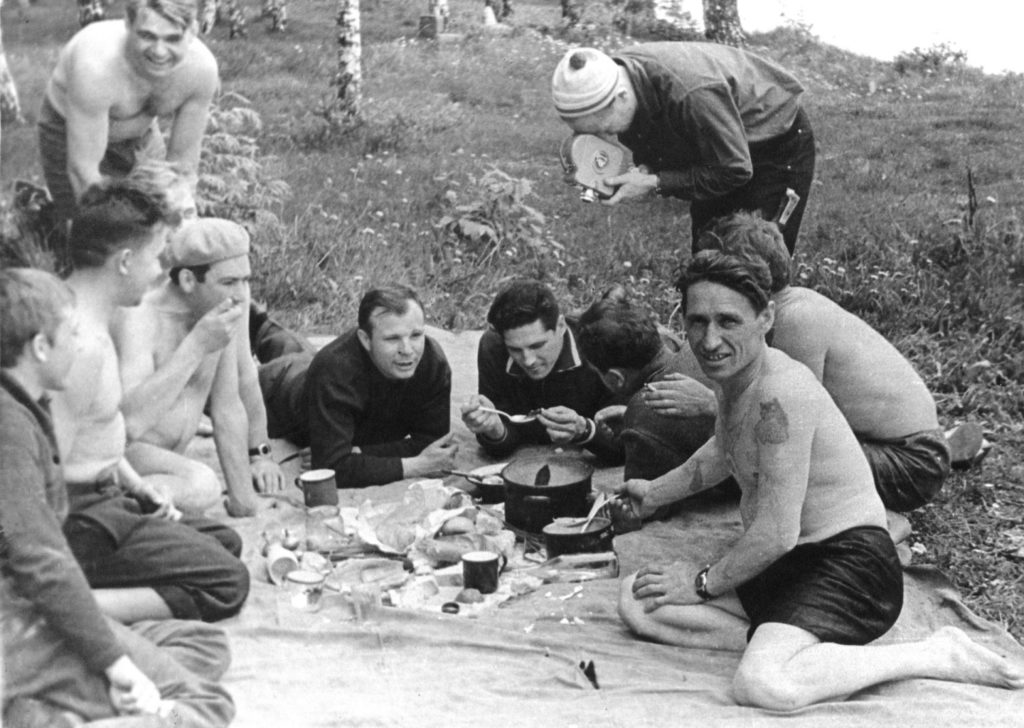

Because there were only 400 days left until the planned date of the flight, the six of chosen ones immediately started a comprehensive, very intense and exhausting training. It is noteworthy that initially, the training devices in the Star Town located near Moscow – where the candidates for cosmonauts and their families were transferred – were yet not ready at this time. That is why they began preparations from participation in theoretical classes and physical exercises in various Moscow medical and scientific institutes, mainly at the Zhukovsky Academy of Aeronautical Sciences.

It was also a period of intense efforts for constructors and engineers working on creation of the Vostok capsule and rocket, on which the first man was to take the pioneer, historical flight into space. On March 9th and 25th, the tests of the spaceships Korabl-Sputnik 4 and Korabl-Sputnik 5 were performed. The results of those tests were considered successful, so in effect the decision to launch a spaceship with a cosmonaut on board was made. The State Commission set the flight date on April 11th – 12th and chose the first cosmonaut. The pilot-candidates were not notified about those decisions until the 10th of April, the day before the flight. From among the candidates for the first space flight, Yuri Gagarin was finally elected. And rumour has it, that the choice was determined by his social background – Gagarin´s father was an unqualified worker, while his mother was a collective farm worker. The fact is that Gagarin was the shortest of the candidates – he was only 157 cm tall, which made him fit perfectly into the tight interior of the Vostok capsule.

On April 12th, 1961, at 6:07 Yuri Gagarin took off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome (Kazakhstan) in the Vostok 1 spacecraft and aboard the Vostok 8K72K carrier rocket – for his flight in the Earth’s orbit, making a one-time (incomplete) lap within 1 hour and 48 minutes. His flight was directed entirely from the Earth, because then it was not yet known how the cosmonaut’s body would behave in space. All controls on board were blocked and the self-destruction installation and reconnaissance devices were also removed from the deck. Eventually, the command of the mission with Sergei Korolov – the main constructor of the Soviet space program at the lead – agreed to place a switch on board the Vostok, enabling disconnection of navigation systems and taking control of the spaceship by Gagarin, if such need arose. The sealed envelope with the code for the switch was placed on the capsule’s deck.

It was assumed that the highest point of Vostok’s orbit would be at the altitude of 230 kilometers. In fact, it amounted a lot more – 327 kilometers. According to the plan the rocket’s engine was supposed to turn off after 2 minutes and 36 seconds of flight, but its shutdown was delayed and because of that, the spaceship was elevated to a much higher orbit. As it turned out later – the reason was the inefficient powering of the control system in the second stage of the rocket. The effects of that could be very serious, because in the case of failure of braking engines the spaceship naturally descending would not enter the dense layer of the atmosphere after 5 – 7 days, but only after about 15 or even 20 days. However, the life support system of the Vostok was not designed for such a long flight – the supply of air accumulated in sixteen tanks containing oxygen and nitrogen could last no more than ten days.

The Vostok ended up on an orbit inclined to the equator at an angle of 65 °, where the time of one lap is ninety minutes. The calculations of the team responsible for preparing and conducting the mission showed that the best conditions for the braking manoeuvre would be during the first or the seventeenth lap of the Earth. If the braking engines were turned on at another time, it would cause the spaceship to land in the sea or in another country. This, in turn, could lead to disclosure of the technological secrets, which the Soviets preferred to avoid. That is why Sergei Korolov – the main constructor of the Soviet space program, decided on one lap of the Earth only.

The earlier mentioned problem with the powering of the control system was not the only one during this mission. Two minutes after the lift off Yuri Gagarin had some problems with speaking into the microphone. After 2 minutes and 30 seconds of flight the pyrotechnic charges fired up, rejecting the Vostok first front cover and exposing the capsule. After another five minutes, the second stage of the carrier rocket separated and Vostok continued to climb using the engine of the third stage. Nine minutes after leaving the launch platform, the cosmonaut was in orbit and began to feel the weightlessness. Gagarin was calmly reporting on his mood and wrote impressions and observations in the logbook. Unfortunately, he did not write much, because at some point the pencil slipped out of his hands and “floated away”. Soon after, the deck recorder’s tape ended. The spaceship was slowly spinning as it was decided not to use fuel for stabilizing manoeuvres to prevent the Sun heating the capsule from only one side. Vostok moved to the East at a speed of almost eight kilometres per second. Less than twenty minutes after the lift off, Gagarin flew over Siberia, heading over the North Pacific. A radio monitoring station located in Petropavlovsk in Kamchatka, determined the speed and altitude of the flight and subsequently, encoded telemetry data was sent to Moscow. After thirty minutes of its flight, Vostok was already over the Pacific Ocean, flying over the darkened hemisphere of Earth.

When Gagarin flew over Cape Horn and the South Atlantic, he heard from the flight controllers the command to prepare for a return manoeuvre. Gagarin made sure that the spaceship was positioned at the right angle. At 10:25 Moscow time (seventy-nine minutes after lift-off) braking engines started running. They worked according to plan – for 40 seconds. While Vostok was over western Africa, small explosives broke the metal straps lashing the cabin to the spaceship’s service module. After disconnecting the module, the cabin shifted violently, and Yuri Gagarin began to feel the G-force again. Suddenly, another problem occurred – the main connection between the capsule and the service module in the form of four metal connectors disconnected correctly, but a thick bundle of electric wires used to supply and transmit data did not disconnect. As a result, for a few minutes the capsule and the module were connected to each other and heading together towards the Earth, constantly tumbling. The Vostok capsule was designed to, with the cosmonaut on board, rotate forward with the thicker layer of the thermal shield behind Gagarin’s back. The disconnection of cables between the capsule and the service module changed the aerodynamic characteristics and weight balance. The spaceship began to whirl rapidly, the braking motors turned off and all indicators in the cabin went out. After a while, they went on again, but there was still no separation. The spaceship slowed down but was still spinning around the three axis. The temperature that generated when the capsule was entering the atmosphere of the Earth, created a layer of ionized gas around it, which prevented any radio contact.

Most likely Korolov was not aware of what was happening in the space. Finally, the bundle of wires burned out and both parts – the 2-tonne service module and the 2.5-tonne capsule, separated from each other. This caused another violent spin of the capsule, which became so strong that the cosmonaut began to lose consciousness. At the height of seven kilometres, the micro explosive charges exploded, and the capsule’s hatch cover dropped out.

Further problems occurred during Gagarin’s ejecting and landing: the reserve parachute activated simultaneously with the main one and additionally, for the few minutes during the landing, the cosmonaut had difficulties with opening the valve allowing him to breath with atmospheric air. Finally, the spaceship safely returned to Earth – the capsule touched the ground at 7:47 GMT, Gagarin landed safely eight minutes later.

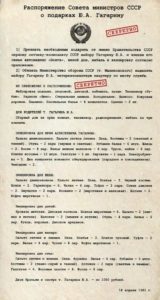

After the flight, Yuri Gagarin immediately became famous and received the highest state decorations. In addition, he was given a holiday at the sanatorium and a GAZ 69 off-road car for his personal use. The problem was that Gagarin did not have a driving license, so the authorities decided to assign a sergeant-driver to him. Shortly after, Gagarin successfully passed the exam later and obtained the license – this allowed him to enjoy another gift from the Soviet government: GAZ-21 “Volga”, special deluxe version – in black colour with blue interior and chrome elements.

The first cosmonaut also received a cash prize of 15 thousand roubles, which he partly spent for purchasing his private car – another GAZ-21, in beige colour. Certainly, those weren´t the only rewards he received, as not only the Soviet government decided to honour Gagarin for his successful flight. Several representatives of the automotive brands from all over the world tried to give Gagarin their products – could you imagine the better advertising those days? However, the first man in space persistently refused to accept such gifts, firstly because of the official reasons (this wouldn´t look good for the hero of the Soviet Union to drive a foreign-produced car) and also because of Gagarin´s nature, he was reported to be a humble, not exalting himself, person.

Finally, there was one company that managed to surprise Gagarin – during his trip to France, Gagarin visited the Renault company where Matra Bonnet sport car caught his eye. When he returned home, a blue Matra Bonnet Djet V S coupé already waited for him at the French embassy. Djet was, those times, an impressive car – with a weight of only 600 kilograms and a relatively modest engine of 95 horsepower, it could reach a speed of 200 km/h. There are several photos existing, showing Gagarin with his Matra Djet, however it is reported he did not use it much. His most used car was the black GAZ-21 he received from the USSR government.

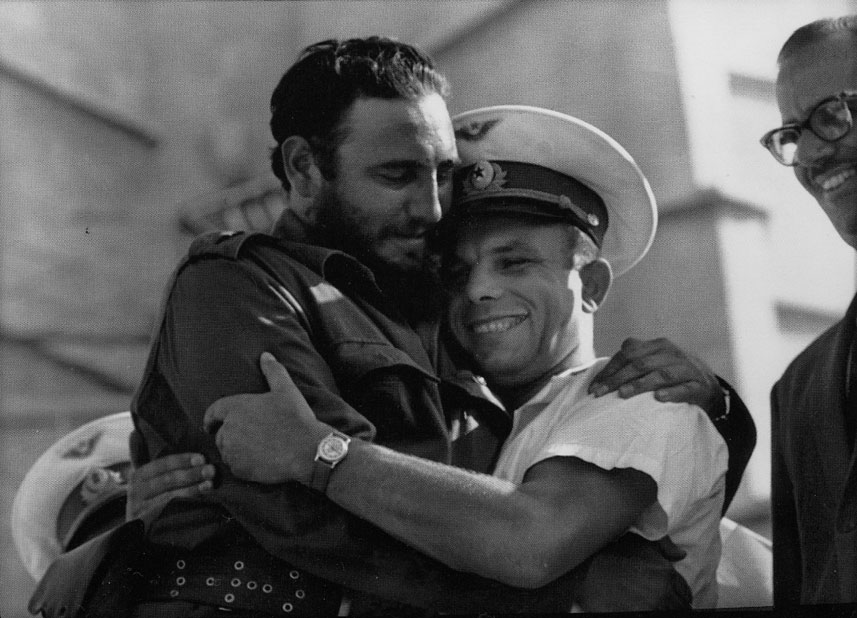

For seven consecutive years since his flight into space, Yuri Gagarin was a real star of Soviet propaganda. He was being invited to various regular and occasional events, such as the May Day parade in front of the Lenin’s Mausoleum at the Red Square in Moscow, where he accompanied the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Wherever he went, the crowds greeted him with flowers and his visit was officially celebrated, Gagarin was also often invited to speak in public. Certainly, he visited other socialist countries and additionally travelled to Australia, Brazil, France, the USA and to Great Britain, where he was invited by the Queen Elizabeth to a gala dinner at Buckingham Palace. More than that, he also visited several African and Asian countries.

Gagarin was promoted to the rank of the Colonel of the Air Force and occupied the managing post in the Star Town training centre. There he worked on the idea of reusable space rockets. At the same time, he still dreamed of traveling to space – including flight to the Moon. Once, Yuri Gagarin was not so far from flying into the space again: he was selected as a reserve pilot in the Soyuz programme. Eventually, the flight was made by the leader pilot – Vladimir Komarov, who did not return from it. Komarov died on board the Soyuz 1, because the ship did not manage to land properly, as planned. In the result of this tragic flight, Gagarin was withdrawn from the space programme by the USSR authorities. There plan was to keep him as far from the space flights as possible. It was planned to continue to use the benefits of his popularity, maybe even offering him a political position.

However, Yuri Gagarin did not intend to give up his dreams about flying. He managed to convince the air force command for allowing him to test the new MiG aircraft. This was, regrettably, the terrible call – on March 27th, 1968, during one of the first flights with MiG-15UTI Yuri Gagarin and instructor pilot Vladimir Seryogin were killed, when their MiG-15 crashed near Chkalovsky air base.

The cause was investigated by several independent investigations, two of them were even led by the KGB itself. Nevertheless, the causes of the disaster remain inconclusive to this day. Among the potential factors that could cause the accident, both wrong preparation of MiG for a flight and dehermetization of the cabin are mentioned. It was assumed that in the second case, the crew could have dive sharp to restore the correct pressure in the cabin, but the pilots lost their consciousness. Others reports mention the poor preparation of Gagarin himself, as he did not sit at the controls of aircraft for quite a long time.

There also exists a disaster-scenario, according to which the pilot of the supersonic Su-15 aircraft that conducted a test-flight in the nearby region, unexpectedly flew at a high speed so close to Gagarin/Seryogin MiG, that the resulting turbulence introduced their machine into a spin which the crew could not manage to stop. As a result of the investigation of the special military commission of colonel Igor Kuznetsov, who re-examined the cause of this accident approximately ten years ago, it was found that Gagarin and Seryogin lost their consciousness through the leaking, most probably from a defective oxygen apparatus, which led to the crash.

In turn, Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony, the authors of the biographical book about Yuri Gagarin: “Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri Gagarin”, wrote that the accident could have been caused by flight controllers who provided the crew with a wrong, outdated weather report.

Gagarin and Seryogin were cremated, the first man in space was honoured by the grave at the Kremlin’s wall. The remains of the aircraft were welded in hermetic barrels and hidden in one of the Soviet military bases and the investigation was closed. It was suggested to Gagarin’s family that assassination could be one of the possible reasons of the accident.

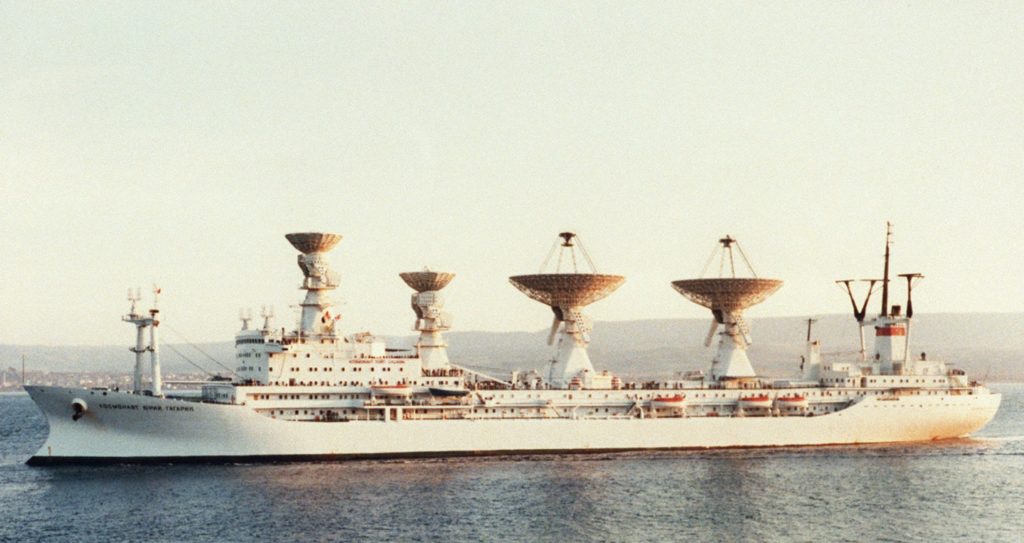

Today, almost 60 years from Gagarin´s historic flight into the space, the memory of the first cosmonaut and the flight is still alive worldwide. Gagarin was, until today, commemorated in many ways, making his name immortal.

During the 1960s in USSR, Yuri was very fashionable name to boy-children. The streets, squares, schools, parks, clubs in many cities were named after Gagarin, and several monuments were erected. In 1968, Gzatsk, the city in the Smolensk region where the first cosmonaut was born, was re-named to Gagarin and today it is a capital of Gagarin administrative region.

The name of the first cosmonaut could be also found in space – there is Gagarin crater on the Moon and one of the asteroids. The Gold Medal of the World Air Sports Federation (FAI) and the KHL ice-hockey league cup were also named after Yuri Gagarin, as well as the seventh produced Sukhoi Superjet 100 airliner. He was also commemorated in music by both domestic and foreign artists – for instance, by the rock group Ундервуд (Undervud) in the song ” Гагарин, я вас любила” (“Gagarin, I loved you”), or by the famous French pioneer of electronic music Jean-Michael Jarre in the song “Hey Gagarin” from his „Metamorphoses” album.

Cover photo by State Space Corporation ROSCOSMOS – the launch of Soyuz MS-11 with three members of the Expedition 58 crew to the International Space Station, December 2018.