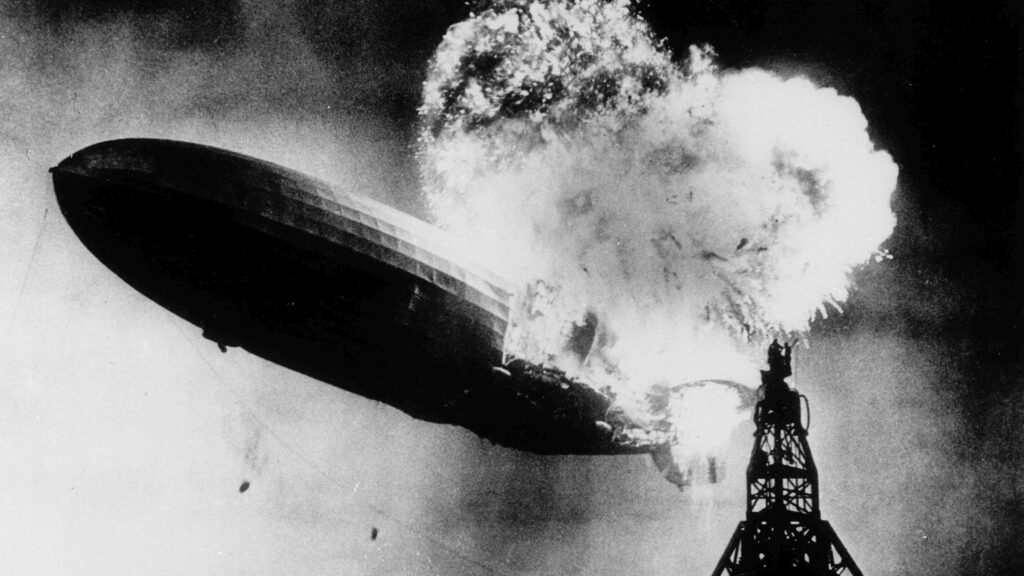

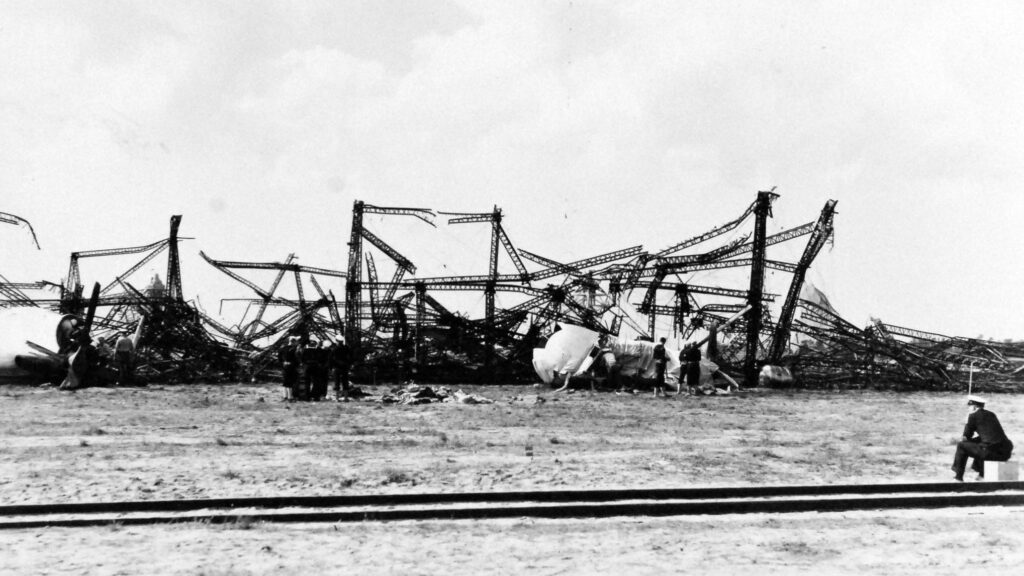

On 6th May 1937, German airship Hindenburg caught fire while landing at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, USA and was completely destroyed, killing thirty six people.

On 6th May 1937, German airship Hindenburg caught fire while landing at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, USA and was completely destroyed, killing thirty six people.

Rigid and semirigid airships appeared in the late 19th century and were then being consistently developed in the 1900s. Dirigible pioneers, such as Alberto Santos-Dumont, Count von Zeppelin or Thomas Scott Baldwin, created many successful designs that radically changed the view on the airship. The aerostat was no longer just another curiosity used only to entertain the crowd but now became a useful tool – they could be used for polar expeditions, military purposes and even regular passenger service.

During the Great War, German airships were widely used for air raids on England, scout and bomber missions on the Eastern Front as well as for long-range reconnaissance and supply flights. Although being slow, large and susceptible to bad weather, there was no aircraft in the early war years that could match a dirigible when it came to range, altitude and flight duration.

Usually called ´zeppelins´ – a term taken from Count von Zeppelin, an aviation pioneer and designer of majority of the German airships – the drigibles of Marine-Fliegerabteilung (Navy Aviation Department) and Die Fliegertruppen des deutschen Kaiserreiches (Imperial German Flying Corps) were spreading fear throughout the England, despite their bombing was far from being accurate. They performed fifty one raids on England, killing 557 people, injuring 1,358 and causing damages worth more than 1.5 million pounds.

It was only in later years of the World War I when development of aeroplanes finally overtook the airships. Then, the dirigible turned out to be an easy target and eventually more than half of the German airships was lost, with attrition rate of 40% – the worst in the whole German armed forces.

After the war, although considered obsolete for combat missions, the dirigibles were being widely used for reconnaissance and surveillance missions. In addition, several attempts were made to turn an airship into a flying docking station for aeroplanes – but they were finally abandoned.

At that time, passenger aeroplanes were still at the beginning of their development. Many of them were just converted from military aircraft and offered a minimum of comfort on board, had a very limited range and could carry only a few people.

There is no surprise that airship still seemed to be a much better solution. Although much slower than any aircraft, it could offer a high level of comfort, transcontinental range and even some entertainment on board.

In 1919, John Alcock and Arthur Brown successfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean in R-34 airship, making the first step towards transatlantic passenger flights. During the next two decades, big-sized dirigibles, designed as luxury airliners for a long-distance routes, became quite popular in the United States, the Great Britain and Germany.

The first German giant passenger airship, designated LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, made its first flight on 18th September 1928. During the next ten years, that dirigible completed almost 600 flights and covered a distance of approximately 1.7 million kilometres. For approximately five years, Graf Zeppelin was flying on regular commercial route between Germany and Brazil, additionally being used for Arctic flights and, moreover, became the first airship to perform circumnavigation flight, that also included the first nonstop air-crossing of the Pacific Ocean.

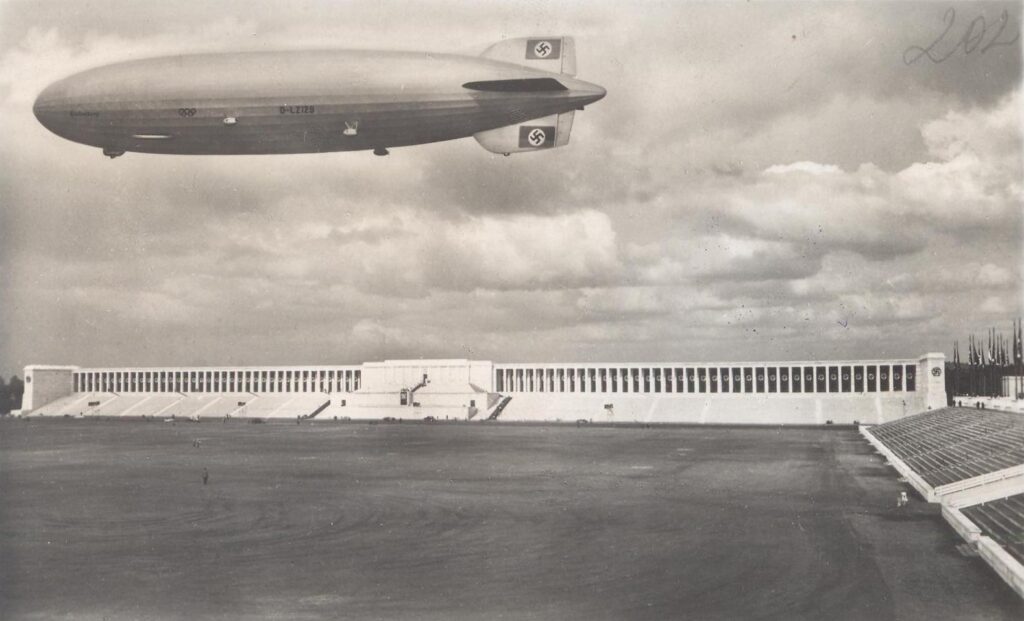

On 4th March 1936, after five years of manufacturing, LZ 129 Hindenburg airship took-off for its maiden flight. It was even bigger and more luxurious than Graf Zeppelin, being – until today – the longest aircraft ever made and the largest airship by volume. Operational flights of the LZ 129 were officially launched at the end of March with a propaganda flight around Germany (Die Deutschlandfahrt), made together with the LZ 127.

On 31st March, Hindenburg took-off for its first transatlantic flight to Rio de Janeiro. Until the end of the year, the LZ 129 completed a total of seven trips to Brazil and ten to the United States. The airship could carry up to seventy passengers and was operated by a crew of sixty. A single trip to North or South America took 50 – 80 hours and return journey usually lasted between 40 and 60 hours.

At that time, Hindenburg was not only the largest aircraft but also the most luxurious one. During a flight, fifteen stewards and five cooks were taking care of passengers. Among special features of the the LZ 129 there was running warm water in cabins, promenade deck for enjoying view from the air and specially-designed glassware, tableware, cloths, napkins and cutlery. Transatlantic tickets were expensive. A return fare to North America could reach almost 40,000 Reichsmark, an equivalent of today´s 10,000 EUR.

The 1937 transatlantic season was opened by a trip to South America, completed in March. Then, on 3rd May, Hindenburg took-off for another journey to the United States. Three days later, delayed by a few storms, the LZ 129 reached the American coast and headed the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst. The airship had to perform a high landing procedure there, known commonly as ´flying moor´ – when the dirigible drops its landing ropes while still at an altitude of approximately 100 m, the ropes are taken over by ground landing crew and then the aircraft is winched down to mooring mast.

Hindenburg dropped its lines at 19:21 hours, four minutes later a fire was seen. It quickly reached gas cells and tanks, causing the tail section of the airship to explode in a few seconds. Then, the tail crashed into the ground and another burst of flame appeared on the nose. Shortly thereafter, the whole airship crashed and exploded in flames. The whole event lasted only about thirty seconds.

At the time of accident, there were 97 people on board of Hindenburg (61 crewmen and 36 passengers) – 35 of them died in the accident (22 crewmen and 13 passengers) plus one fatality from the ground crew.

Usually, landing of Hindenburg was a kind of an entertainment, being witnessed and commented by several radio stations, covered by photo reporters and newsreel film cameras, as well as attended by general public. It was the reason that disaster was extremely well-documented, although no camera caught the very moment when the fire started.

That led to several speculations regarding the exact reason of the fire and place where it started. Regrettably, the witnesses reported a few different sections of the airship where they saw the fire first, some said about traces of leaking gas or static electricity sparks seen on the outer skin. Cause of the ignition became a subject of investigation and there were few hypothesis made, such as sabotage, electrostatic impulse, lightning strike, engine failure, fuel leak and punctures.

Nevertheless, the exact cause of fire still remains a mystery, as well as the reason why the fire spread so fast and covered the entire airship in less than 20 seconds. Most probably, there is no single answer to those questions and there was more than one factor that led to that disaster.

As mentioned above, the Hindenburg disaster was well covered by media and the news spread the world. Shocking pictures and newsreels with images of the exploding LZ 129 and burning people, caused the airship was no longer considered as safe and comfortable way of travelling. There is no exaggeration in saying that the LZ 129 accident concluded the era of dirigibles.

Certainly, Hindenburg was just one of many examples, as many other huge dirigibles also suffered from similar disasters. Already in 1923, ex-German LZ 114, at that time operated by the French Navy as Dixmude, exploded in mid-air killing all 50 people on board. In 1930, one of two British flag airships – designated R101 – crashed in France, killing 48 people. Three years later, USS Akron, leading airship of the US Navy, crashed off the coast of New Jersey with 73 fatalities.

Nevertheless, none of the previous accidents was so widely witnessed by general public and media as the Hindenburg disaster was. It was the LZ 129 that became the iconic symbol of the end of airship golden years.

Cover photo: ´Hindenburg´ burning, US Navy photo via Wikipedia Commons, public domain