On 9th September 1942, a Japanese Yokosuka E14Y “Glen” floatplane dropped two incendiary bombs in the mountains of Oregon. The raid marked the first time that enemy aircraft had carried out an air raid on the contiguous United States.

From the very beginning of the World War II in the Pacific, the Japanese forces tried to scare the American public and create feeling of being under constant threat.

On 23rd February 1942, the I-17 submarine sneaked into the Ellwood Oil Field channel near Santa Barbara, California, and fired sixteen shells at that oil storage facility. Although that first attack on the US soil caused minor damage, it triggered the so-called “invasion panic” that turned into the “Battle of Los Angeles” – a series of fake reports regarding Japanese aeroplanes seen in that area and following counteractions of the US artillery units.

Then, in early June 1942, the Japanese Imperial Navy performed two aircraft carrier raids, launching eighty-six aeroplanes against military facilities on Dutch Harbor, Amaknak Island in the Aleutian archipelago. The American forces suffered moderate losses of forty-three killed and fifty wounded, as well as fourteen damaged aircraft. In addition, and to surprise of the American public, the air raid was followed by successful invasion on Kiska and Attu islands. Although the attack was performed on a faraway area of the Aleutian Islands, it immediately increased the aforementioned sense of danger and additionally inspired rumours about a full-scale Japanese invasion on the West Coast.

Later in the same month, the I-25 submarine surfaced at Fort Stevens base in Oregon and then fired seventeen shells at the military facilities in the mouth of Columbia River. Although the raid caused almost no damage, it kept the threat of invasion – and the related sense of panic – alive.

Nevertheless, the Japanese armed forces were aware of the close-to-zero damage caused by both submarine attacks. On the other hand, Japan had no strategic bomber capable of performing air raids over the United States territory. As a consequence, another idea was put into action.

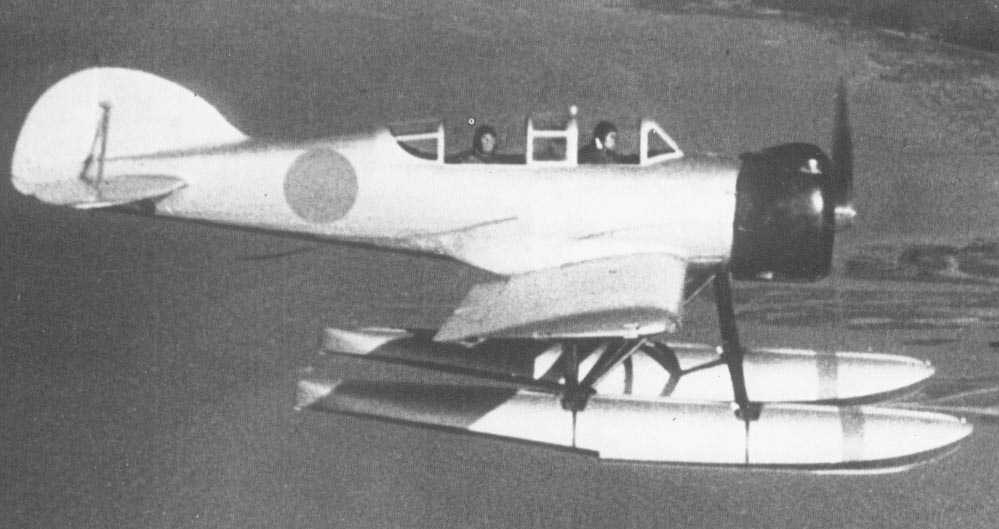

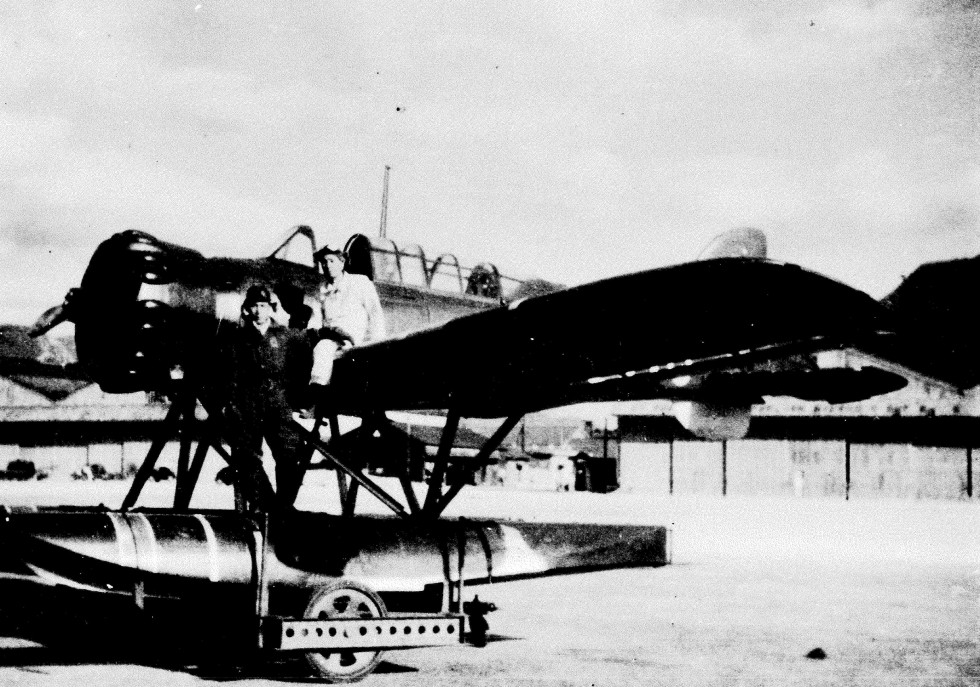

Already in 1941, the Warrant Officer Nobuo Fujita proposed to use floatplanes against the US military bases, production sites and other similar facilities. A Yokosuka E14Y aircraft (Allied reporting name “Glen”) could be carried by a B-1 type submarine across the Pacific and then dispatched against targets along the West Coast or the Panama Canal.

Initially, Fujita´s idea failed to gain enough interest from the Japanese Navy authorities. Thus, he had no other choice than to prove his concept right. During the following months, Fujita performed several reconnaissance flights with his E14Y floatplane. He managed to fly over Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart in Australia, Fiji and Kodiak Islands, as well as Wellington and Auckland in the New Zealand – being the only Japanese pilot to overfly New Zealand during the World War II. On all those missions, Fujita´s aircraft was carried to the operational area in submerge, by the already mentioned I-25 submarine equipped with a special, watertight hangar.

Having proved his initial idea, Fujita was assigned the task to perform a mission against the United States mainland. Nevertheless, a single floatplane carrying just a limited bomb load was not capable to do any serious damage on any military object. Aware of this, the Japanese instead opted to use incendiary bombs against forest areas, hoping they would start an uncontrolled wildfire and, as a result, a significant damage that would be noticed by the American public.

In the morning of 9th September 1942, Fujita and his second crewman, Shoji Okuda, took-off in their E14Y aircraft from location off Cape Blanco. During that mission, the “Glen” was carrying only two incendiary bombs, each weighing 76 kilograms. They were dropped into the forest on Wheeler Ridge, in the vicinity of Brookings, Oregon.

Unfortunately for the Japanese, the “Glen” was spotted by the US fire watch wardens. Although they were unaware of the bombing, they saw and reported the resulting smoke plume. The wardens managed to contain the fire until firefighters arrived. As a result, Fujita’s raid caused only minimal damage to the forest.

Nevertheless, the raid alarmed the US armed forces that almost immediately launched a mission to seek and destroy the Japanese submarine. The I-25 was located, and attacked, by the USAAF aircraft shortly after the “Glen” was stored in its hangar. Soon another three aeroplanes and a Coast Guard ship arrived to the area but the submarine managed to escape with almost no damage.

Fujita and Okuda had to wait three weeks for an opportunity to repeat their mission. This time, expecting the Americans were still on alert, they decided to perform a night-time raid. It was not an easy task, as blackout was imposed on the coastline – with lighthouses being the only exception. Using that only light as a navigation aid, Fujita crossed the coast and flew into the US mainland. Then the Japanese crew blind-dropped the bombs over the area they thought it was a forest. In his official report Fujita mentioned he saw them explode but no traces of fire were confirmed by the wardens.

The E14Y crew planned to perform another raid, but it was cancelled due to severe weather conditions. Then, the I-25 returned to the ocean and focused on chasing the US ships.

In 1944, the Japanese attempted to start forest fires along the West Coast once again, in the hope to cause panic and chaos. This time, they used high-altitude hydrogen balloons, launched from the Japanese islands. The jet stream at an altitude of 30,000 feet was expected to carry them more than 5,000 miles to the US mainland.

Approximately 9,000 balloons were launched, but only a few hundred of them managed to cross the Pacific Ocean. Although they were reported in several locations deep inside the mainland – including Michigan, Iowa, and Canada – they caused no significant damage and killed only six people in total.

Nobuo Fujita continued his service as reconnaissance and instructor pilot, surviving the war. In 1962, he was invited to Brookings – although that idea raised some controversies in the United States. Nevertheless, he was treated there with respect and then repeated his visits there three times in the 1990s. As an apology, Fujita donated a 400-year-old katana sword, that belonged to his family, for the city council, assisted in gathering money for a city library and students exchange, as well as planted a tree at the location where he dropped his first bomb.

The Japanese pilot died in September of 1997, at the age of 85. His ashes were buried at the bomb site in Brookings, Oregon.

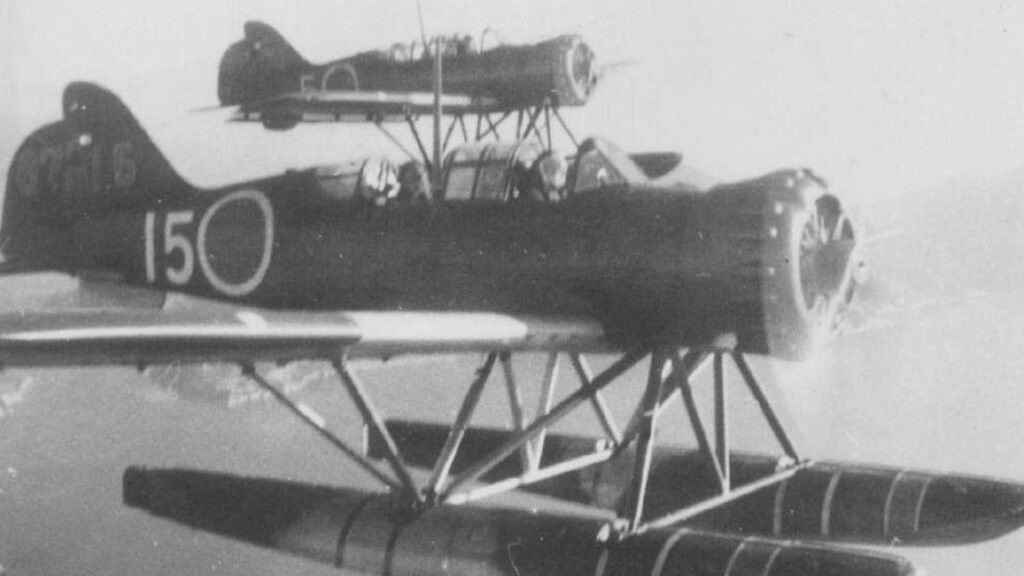

Cover photo: Two Yokosuka E14Y “Glen” aircraft in flight (photo: Wikipedia, public domain)