Today marks the 135th anniversary of the first manned flight in a heavier-than-air aircraft, successfully performed by the French aviation pioneer Clément Ader. Although the flight was uncontrolled and reached a height of only twenty centimetres, his achievement marked a significant milestone in the history of aviation.

Today marks the 135th anniversary of the first manned flight in a heavier-than-air aircraft, successfully performed by the French aviation pioneer Clément Ader. Although the flight was uncontrolled and reached a height of only twenty centimetres, his achievement marked a significant milestone in the history of aviation.

The beginnings of powered flight in heavier-than-air aeroplanes are commonly associated with Orville and Wilbur Wright. In 1903, they made aviation history with the first manned and controlled flight of this type of aircraft. Nevertheless, the development of the aeroplane dates back much further and abounds with many fascinating inventions and early aircraft designs, as well as a whole galaxy of great pioneers whose names are nearly forgotten today.

About a year ago, we recalled the story of Félix du Temple de la Croix, who is credited with the first officially observed flight of a powered aircraft of any kind – although neither controlled nor manned. This time, we would like to recount the history of another great French inventor and aviation pioneer – Clément Ader.

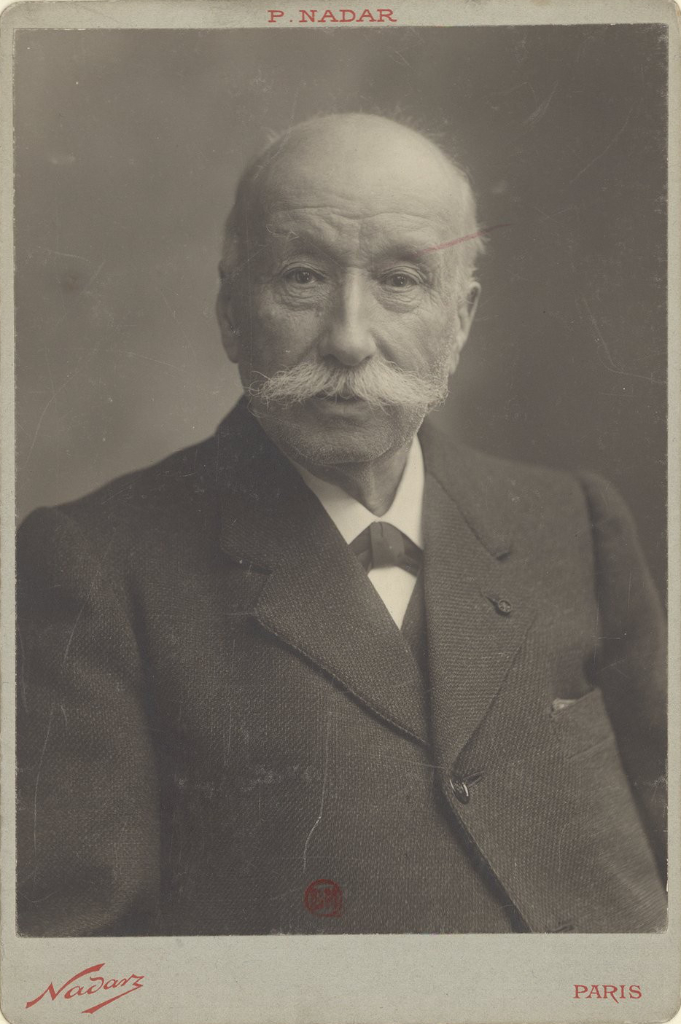

Clément Ader was born on 2 April 1841 in Muret, near Toulouse. His family had been in the carpentry business for generations, and Clément was expected to continue that tradition. However, it soon became clear that the young student had a real talent for mathematics, and consequently, his father allowed him to study in Toulouse. In 1862, Ader graduated as an electrical engineer, and the following year began working as a construction manager for a local railway company.

In 1866, following the death of his mother, Ader returned to Muret. In the same year, he filed a patent for his first invention, a rail-laying machine. A few years later, a new invention sparked his interest – the velocipede. Ader devoted himself to improving the vehicle and enjoyed some success before his work was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War. During the war, he was involved in developing military observation kites and soon discovered aviation as his second great passion.

After the war, Ader briefly worked for a ceramics company. He then decided to move to Paris with his father and focus on his own projects in the fields of engineering and aviation.

One of Ader´s early works was a prototype of a caterpillar vehicle he invented yet before the war. Although the invention attracted some interest, Ader was unable to find any buyers.

Fortunately, he fared better with his next ideas. In 1878, Ader improved Bell’s telephone, and within a few years he had established the Paris telephone network. He also invented the théâtrophone – a telephonic distribution system allowing subscribers to live listen to opera and theatre performances in stereo. In 1903, Ader was most probably the first to develop a V8 engine.

In parallel, Clément Ader was working on his aviation projects. Inspired by Louis Pierre Mouillard’s studies of bird flight, the French inventor built his first aircraft in 1886. He named it Éole, after the Greek god of wind, Aeolus. This bat-like aeroplane was powered by a lightweight 20 hp steam engine, also designed by Ader.

On 9 October 1890, Clément Ader made his first attempt to fly the aeroplane. He managed to lift the Éole into the air, performing an uncontrolled flight over a distance of approximately 50 metres at a height of about 20 centimetres. This achievement is widely recognised as the first manned flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft in the history of aviation.

In the following years, Ader continued to improve his designs. In 1893, he built his second aircraft, initially named Zéphyr (after Zephyrus, the Greek god of the west wind), but commonly known as Avion II (from avis, the Latin word for “bird”) or Éole II. There is no evidence that the aeroplane was ever completed or flew. However, Ader later claimed that he had managed to cover a distance of 100 metres, although there were no witnesses to confirm this achievement.

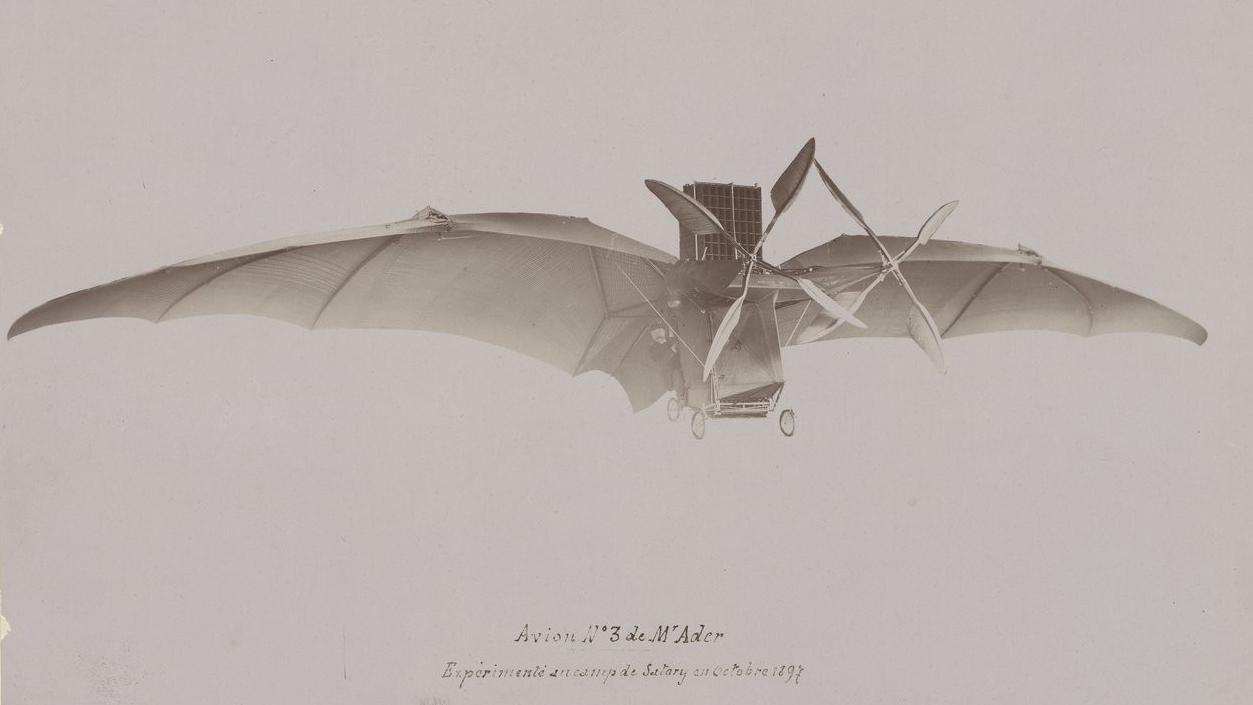

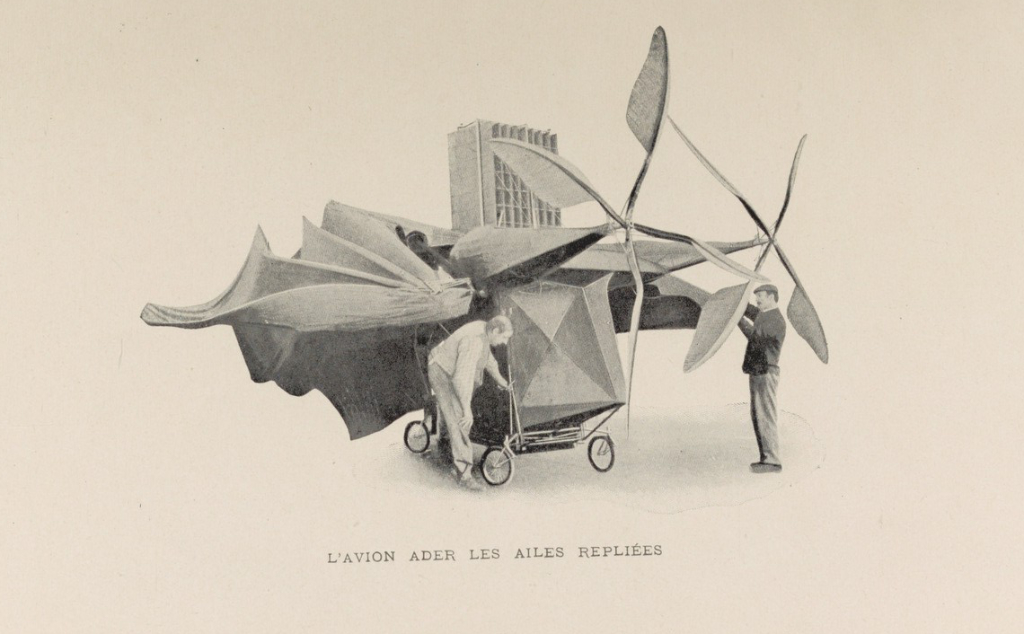

In 1897, Ader completed his third aeroplane, known as Aquilon (the god of the north-east wind) or Avion III. Like its predecessors, the aircraft had a bat-like design, but it was now equipped with a rudder to enable flight control.

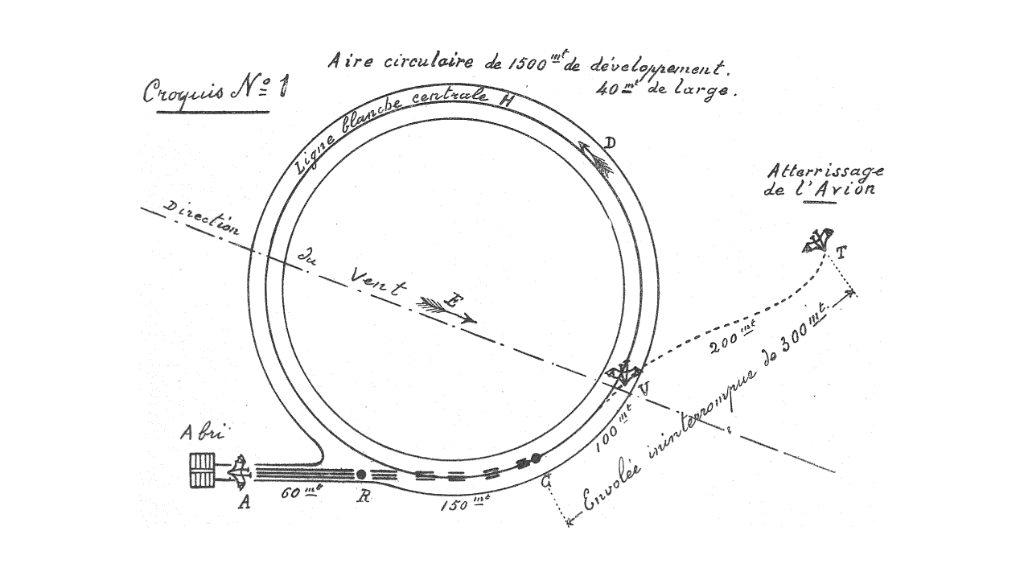

The third Ader´s aircraft was developed with financing from the French Ministry of War, and test flights were planned to take place at the Satory military base near Versailles. The aeroplane was expected to follow a circular route while taxiing and during flight. The first tests began on 12 October 1897, but no successful take-off was recorded.

After two days of trials, the Avion III left the track, continued to taxi for another 200 metres, and then stopped. Disappointed by its performance, the French military authorities decided to terminate further evaluations and withdraw funding. Moreover, all reports from the trials were classified and not made public until 1910.

As a result, Clément Ader returned to his work in electrical engineering, which brought him fame and financial stability. Over the next years, he focused on telegraphy and long-distance communication, filed several patents related to signal transmission, and worked on automotive engines.

Nevertheless, Ader never lost his passion for aviation. He actively promoted its development and conducted several successful theoretical studies on the future of aircraft. His book L’Aviation Militaire (the Military Aviation), published in 1909, became extremely popular and went through ten editions in just five years. In this work, the French aviation pioneer established the principles of aerial warfare and, for the first time, outlined the concept of a modern aircraft carrier. He also provided advice and assistance to other French aviation pioneers, evaluating their projects.

In his later years, Ader retired to his vineyard near Toulouse. He died on 3 May 1925, aged 84.

Although his name has largely been forgotten today, Clément Ader was one of the true “fathers of aviation”. His pioneering work not only influenced the development of the aeroplane but also contributed greatly to popularisation of the aeronautics.

Moreover, the French word avion, now commonly used to refer to a heavier-than-air aeroplane, is derived from the name of Ader’s aircraft. It was later popularised by Guillaume Apollinaire, who wrote a poem entitled L’Avion in 1910.

Airbus has honoured Clément Ader’s aviation legacy by naming one of its facilities Site Clément-Ader. There is also a research laboratory in France that bears his name. In addition, several streets in France and Canada are named after the French aviation pioneer.

The Avion III has survived to this day and is exhibited at Musée des Arts et Métiers (Museum of Arts and Crafts) in Paris.

Cover photo: Avion III (source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France, ark:/12148/btv1b8514000t, cropped)