On 7th September 1920, on their way from Italy to Finland, two crews of the Finnish Air Force made an attempt to fly across the Alps in Savoia S.9 flying boats. Regrettably, they never reached their destination, as both aircraft crashed in Switzerland, with all aviators dead on the spot.

On 7th September 1920, on their way from Italy to Finland, two crews of the Finnish Air Force made an attempt to fly across the Alps in Savoia S.9 flying boats. Regrettably, they never reached their destination, as both aircraft crashed in Switzerland, with all aviators dead on the spot.

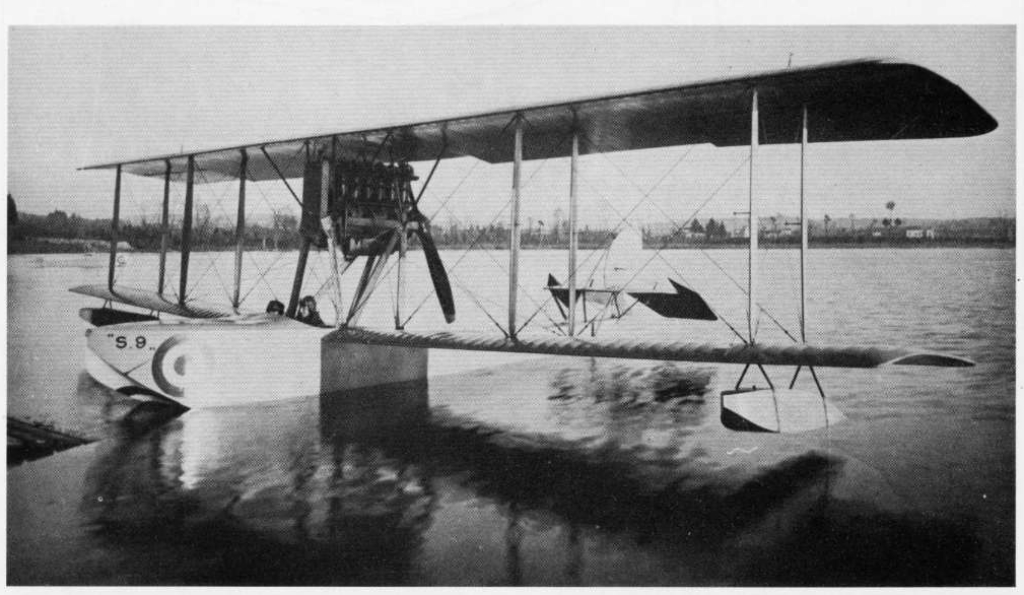

In 1915, an aviation company was founded in Italy, initially aimed to manufacture flying boats under license acquired from the Franco-British Aviation Company. However, within two years Societa Idrovolanti Alta Italia – SIAI (the Seaplane Company of Upper Italy) developed its first own aircraft, designated SIAI S.8.

The aeroplane, designed by Raffaele Conflenti, was a biplane flying boat based on the Austro-Hungarian Lohner. In a short time, the S.8 entered service with Servizio Aeronautico della Regia Marina (the Italian naval aviation) and more than 170 examples of the aircraft were built until the end of the Great War.

Shortly after concluding his successful development of the S.8, Conflenti began to work on another reconnaissance flying boat. In 1918, the aircraft performed its maiden flight and shortly after the war was approved for service with the Italian Navy, designated SIAI S.9 (also known as Savoia S.9). Yet in 1918, Conflenti designed one more reconnaissance flying boat, designated S.12. It was shortly followed by S.13 and S.16, both introduced into the market in the next year.

Although it was not that long ago from the end of the Great War, the SIAI company wanted to increase sales of its military aircraft. The newly established air forces and naval aviation branches of many European countries seemed to be the right target.

Therefore, the Italian aviation manufacturer began to participate in the famous Schneider Trophy aviation race, as well as organised – in cooperation with Regia Marina (the Royal Italian Navy) – a series of long-range flights to promote its flying boats. In August of 1919, the first of such operations began, led by the famous Italian naval aviator and the Great War hero, Umberto Maddalena.

Within this flight, the S.9 and S.13 flying boats flew from Italy to the Netherlands, to participate in Eerste Luchtverkeer Tentoonstelling Amsterdam (the First Air Transport Aviation Exhibition) held in Amsterdam between 1st August and 14th September 1919. Then, both aircraft and their crews flew to Sweden where the SIAI flying boats were presented to military authorities of the Scandinavian countries.

In April of 1920, Maddalena participated in the Munich Aviation Meeting with S.17. Later that year, he flew with another SIAI hydroplane to Sweden.

In September of 1920, Umberto Maddalena led the marketing tour of SIAI S.16. Together with aviation journalist Guido Mattioli, he flew the Italian aircraft from Sesto Calende to Helsinki, completing the then longest flight with the flying boat in history of aviation. The S.16 promotional tour included stopovers in Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Finland.

Slowly, the marketing efforts of the Italian aviation manufacturer yielded the first results, although not so big as expected. Four examples of the S.13 were acquired by the Swedish Navy, a single S.13 was purchased by Rudolf Olsen, the Norwegian Consul General to Italy, and donated to the country´s air force. In addition, the Italian Navy handed over one example of the S.9 to the newly established Finnish Air Force.

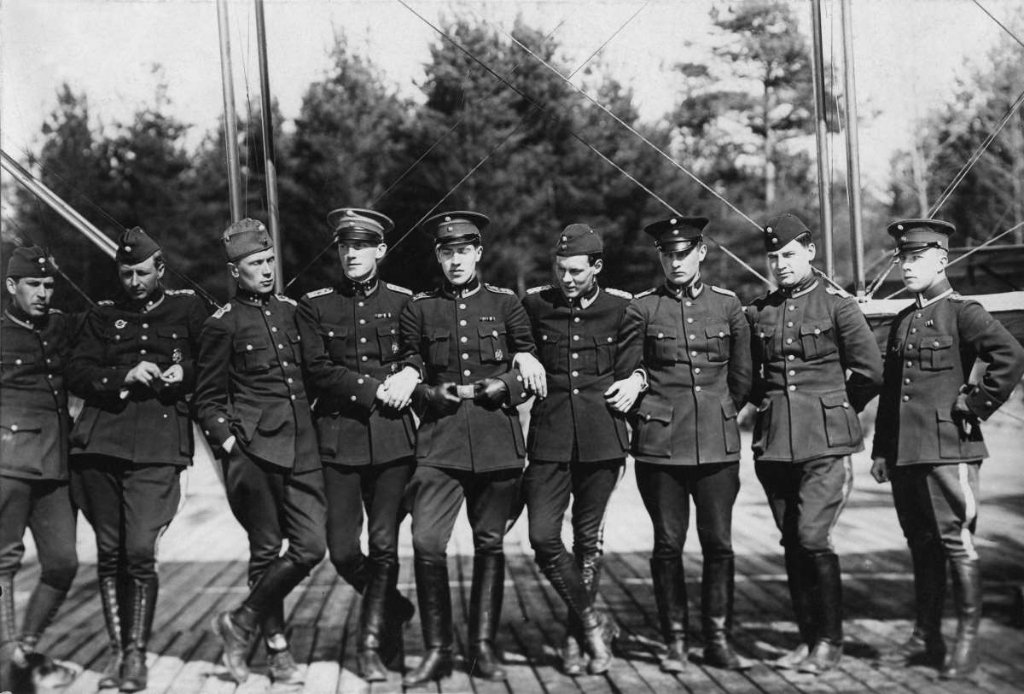

In the summer of 1920, the Finnish military authorities decided to purchase another two examples of the S.9 flying boat. Therefore, a three-membered group of Finnish aviators was sent to Italy and assigned the task to take over the aeroplanes and fly them to Finland.

The team was led by Major Väinö Mikkola, one of the Finnish aviation pioneers, experienced military pilot and commanding officer. The two other members of the group were Lieutenant Äly Rae Durchman and 2nd Lieutenant Carl-Erik Leijer.

The Finnish aviators arrived to the SIAI factory after a long journey through Sweden, the United Kingdom and Germany. Nevertheless, it turned out that their aircraft were not ready, and they needed to stay in Italy until the beginning of September.

Early in the morning of 7th September 1920, the two S.9 flying boats took-off from Lake Maggiore and headed north. The first aircraft was crewed by Mikkola and Durchman, the second was piloted by Leijer and also carried on board the Italian aviation mechanic, Carlo Riva, who was sent to Finland to train the ground crew there.

The on-board equipment of the S.9 was quite simple and included just some basic instruments, according to the standard of the time. Flight navigation was performed solely basing on map, compass and watch, and only contact the crews had with each other was visual, as none of the flying boats was equipped with a radio.

It still remains not fully confirmed until nowadays what exactly caused the crews lost contact with each other during the flight. They were spotted near the Italian border, still flying in formation, but then the aircraft split and continued their journey separately.

Around 8:00 hours, the S.9 flew by Leijer landed on the Rhein in Switzerland, in the vicinity of Ragaz city. After receiving information about their exact location, Leijer took-off and headed Zurich.

Approximately one and a half hour later, the aircraft was spotted over the Lake Zurich during an uncontrolled descend. A moment later the S.9 crashed into the lake, near the village of Zollikon, killing the crew on the spot. The final stage of the flight and the crash were witnessed by many people and some of them claimed to see some parts falling off the aircraft shortly before it began to dive.

The second Finnish aeroplane disappeared, and its fate remained a mystery for more than a month.

Five weeks after they took-off from Lake Maggiore, wreckage of the aircraft flew by Mikkola and Durchman were found on Glatscher da Gliems in Glarner Alps, at an altitude of about 3,000 metres. The crash occurred, according to the onboard clock, at 8:47 hours and the crew was killed on the spot.

An investigation was carried out by the Swiss authorities and the conclusion was that, in both cases, the crash and death of the crews was caused by loose of the propeller blade. In case of the S.9, the biplane equipped with engine mounted in pusher configuration and the propeller spinning through a cut made in trailing edge of the upper wing, any failure of the blades usually meant serious damage on the aircraft and, in consequence, tragic end of its crew.

During the investigation it was found that two different kinds of glue were used to assembly the propeller blades, a malpractice that should not happen at any aircraft factory. In the era of early, all-wooden aeroplanes, the gluing process was one of the most complicated stages of production and therefore performed under close supervision.

In conclusion, the Finnish authorities immediately classified the case as a sabotage and a crime against the newly established country and its armed forces. However, that manufacture fault could be also a mistake due to hurry – we should not forget that when the Finnish aviators arrived to Italy, the aircraft were not yet completed. There was also a hypothesis that strong down drafts, frequently occurring at the Alpine ridges, might cause turbulences the lightweight construction of the flying boat could not withstand.

The three Finnish aviators were buried at Hietaniemi cemetery in Helsinki. Their funeral was an official state memorial ceremony with participation of the highest Finnish military authorities, as well as large numbers of Helsinki citizens.

In the late 1950s, more remains of the Mikkola and Durchman aircraft were discovered and, for a while, speculations on the reasons of the crash took the spotlight again. Regrettably, without any new conclusions.

Only in 2020, on the centenary of the tragic flight across the Alps, the Finnish director and producer Ilkka Liettyä released a documentary named Alppilentäjät-Revision (The Alpine Pilots – Revision), in which he tried to solve the riddle of the S.9 accidents.

Although the investigation made by Liettyä and his team did not exclude the propeller malfunction as the direct cause, it also suggested a navigation error as possible cause of the tragedy.

According to that theory, the two flying boats intended to cross the Alps over the Gotthard Pass, at 2,106 metres. The Finnish crews flew along the valley of Ticino river and it should led them directly to the pass and then, after flying over the main Alpine ridge, to Zurich. And that route was, with high probability, followed by the first aircraft, crewed by Leijer and Riva.

However, and from unknown reason, Mikkola and Durchman left that route and turned into the Brenno valley. According to hypothesis developed in the Finnish documentary, that navigation error occurred over Biasca, where Ticino and Brenno rivers converge. At this point, the narrow Ticino valley turns west, while the Brenno valley has much wider mouth and leads almost directly north.

And exactly that view could deceive the Finnish aviators and made them to fly into the Brenno valley. Regrettably for Mikkola and Durchman, that valley dead ends in Adula Alps with peaks exceeding 3,000 metres.

Nevertheless, Mikkola and Durchman made it through and then crossed the Rhine valley just to realize their next challenge – to cross Glarus Alps. Disastrously for them, this mountain ridge has no clear pass to north and the only way was to fly over its peaks, at altitude exceeding 3,600 metres, so significantly higher than the Gotthard Pass route.

Most probably, the Finnish aviators continued to fly directly north and soon they found themselves in an unforgiving predicament with no way out. Narrow valley between the high peaks did not allow the aircraft to turn back and the only way was to climb higher, hoping to cross the ridge. Regrettably, the 300 hp Fiat engine that powered the S.9 was not enough to handle both the climb in thin air, down drafts and turbulences. In consequence, the journey of Mikkola and Durchman tragically ended somewhere over the Gliems Glacier.

Sources:

Alppilentäjät-Revision, Ilkka Liettyä, 2020

Väinö Mikkola – alppilentäjän elämä kuvina ja esineinä, Susanna Valliuksen, 2018

Umberto Maddalena, Pierro Crociani, 2006

1919-1922. Gli anni perduti dell’aviazione italiana, Roberto Gentilli, 2020

Cover photo: Tödi peak and Gliemsgletscher from 4000 m, 1919 (ETH Library Zurich, Image Archive / LBS_MH01-002522, Public Domain)