Those roaring twenties, the ´golden years´ of aviation… This was a time when aviators outdo themselves, pushing the limits of what is possible. Aviation records were set one after another and reports of new outstanding achievements circulated the media on regular basis. Among those amazing aviation pioneers was a Polish pilot – Stanisław Skarżyński. Nowadays, it has been exactly 87 years since the day he went down in a magnificent way in the history of aviation.

Those roaring twenties, the ´golden years´ of aviation… This was a time when aviators outdo themselves, pushing the limits of what is possible. Aviation records were set one after another and reports of new outstanding achievements circulated the media on regular basis. Among those amazing aviation pioneers was a Polish pilot – Stanisław Skarżyński. Nowadays, it has been exactly 87 years since the day he went down in a magnificent way in the history of aviation.

Stanisław Jakub Skarżyński was born on 1st May 1899 in Warta, a city situated in the bend of the river of the same name. Since his childhood, Skarżyński had a penchant for aviation and started with making aeroplane models. However, his road to aviation did not happen immediately, being long and winding one.

Starting his elementary education in Warta, Skarżyński often moved and changed the second-grade school, finally, between 1915 and 1918, attending the Secondary Modern School in Włocławek. There he joined the local independence organisation and also the Polish Military Organisation. Within the latter Skarżyński graduated the underground military school and received a rank of Sergeant Officer Cadet.

In 1918, Skarżyński passed all exams of his secondary school and moved to Warsaw where he was going to continue his education at the Warsaw University, Faculty of Chemistry. Nevertheless, yet the same year he returned to Warta and volunteered for the Polish Army. Shortly after he became a commander of the unit responsible for disarming German soldiers and restoring Polish authority in the area. Finally, he became the city commandant of Warta.

In December of that year Skarżyński was promoted to staff sergeant and enlisted the 29th ´Kaniów´ Rifles Regiment in Kalisz, starting his military career in infantry. In the following years he graduated from the School of Cadets, was promoted to second lieutenant and took a part in the Polish-Soviet War. On 16th August 1920, during the battle of Radzymin, Skazrzynski was seriously injured in his leg. Despite the long treatment, he began to limp and therefore had to abandon the infantry service – and aviation seemed the best choice.

Skarżyński´s determination won him the transfer to air force and he soon began the flight trainings at School of Pilots in Bydgoszcz. Sometimes, the things are not easy at the beginning and Skarżyński experienced this in his own way. Already during his first flight, the aeroplane caught fire – fortunately, he managed to land it safely.

Eventually, Skarżyński finished his aviation training in 1925 and, as a young pilot, was assigned to the 1st Aviaregiment in Warsaw, based at Pole Mokotowskie airfield. Two years later he was appointed captain and in 1928 he was given command of 12th Combat Squadron, where he stayed until January 1930. During this period, Skarżyński additionally interned at Romanian Air Force.

This was also the beginning of his dreams about the long-distance flights. And soon, Skarżyński started to make them happen.

He first gained attention in 1931 when, together with Lt. Andrzej Markiewicz, made a flight around Africa. Flying a Polish liaison aeroplane PZL Ł.2 ´SP-AFA´, they flown the route of 25,770 kilometres from Warsaw, through Athens, Cairo, Khartoum, Kisumu, Abercon, Elisabethville, Luebo, Léopoldville, Lagos, Abidjan, Bamako, Dakar, Port Etienne, Agadir, Villa Cisneros, Casablanca, Alicante to Paris and then back to Warsaw.

It was a long and dangerous flight, quite eventful in respect of the technical problems. The engine required to be repaired several times and, in addition, one of the cylinders broke away during the flight, forcing Skarżyński to perform an emergency landing at Riberac, France. Despite all issues with the engine, Skarżyński refused to replace it with another unit, strongly insisting on finishing the flight with the originally mounted one.

That African adventure made him a famous man of Polish aviation, but the biggest surprise was still about to come. Yet during the flight around Africa, an idea of flying across the Atlantic Ocean sparkled in Skarżyński´s head for the first time, since then he just needed to bring it into existence.

Obviously, he would not be the first pilot that made it – there was already John Alcock and Arthur Brown in 1919 and Charles Lindbergh in 1927, who successfully crossed the Atlantic – but he would be the first Polish to achieve this. There were already two unsuccessful attempts, made by Polish Major Ludwik Idzikowski and Major Kazimierz Kubala, flying an Amiot 123. The first flight in 1928 concluded in an emergency landing off the coast of Spain, a year later, during the second attempt, their aeroplane crashed on Graciosa Island, killing Idzikowski.

However, crossing the Atlantic Ocean was not a goal in itself. Skarżyński´s idea was even more complicated and more challenging – he wanted to perform a record-breaking flight from Warsaw to Rio de Janeiro, flying a distance of approximately 18,000 kilometres. What he needed, was an aeroplane suitable for such adventure flight.

The choice was made for a new Polish sport aeroplane RWD-5, a small two-seat monoplane in high-wing configuration, originally powered by 120 hp de Havilland Gipsy Major engine with wooden, two-blade propeller. Nevertheless, the extreme flight to Rio de Janeiro required several modifications to be made.

The rear cabin equipment was removed and replaced by 300-litre fuel tank, two additional tanks of 113 litres each were installed in the wings, just next to the standard ones. With the new fuel installation, the take-off weight increased to 1,100 kg, comparing to original 760 kg, and it required many of the standard equipment to be removed, including not only the passenger seat and other redundant items, but also radio or even instrument panel backlight system. On the other hand, the pilot´s seat was equipped with rubber cushions, enhancing the comfort during the long flight and additionally with the possibility to inflate them in case of landing on the sea surface. Finally, the unladen weight was reduced to just 446 kg and maximum take-off weight to 1,100 kg, even less than the serial manufactured RWD-5.

After successfully completing the flying tests, the silver-painted aeroplane was recognized as RWD-5bis and registered as SP-AJU. Skarżyński completed his medical examination and that meant both the pilot and his aeroplane were ready for the journey. As opposed to other record-breaking adventures, Skarżyński´s flight had no media coverage. The purpose of his flight, the idea behind it and all those preparations were known just to a small group of people and kept in secret as long as possible.

There are several explanations for why Skarżyński decided to act this way. First of all, he personally was not looking for any attention and preferred to avoid a possible public disappointment if the flight had to be cancelled or if something else went wrong. Secondly, he thought that it was much better to make decisions without any pressure, that certainly would exist if the media were reporting about the preparations and the journey. This, surprisingly, worked well, but the only inconvenience was that along the route, Skarżyński had to hide the purpose of his flight and the final destination.

On 28th April 1933, around 8:00 in the morning, Stanisław Skarżyński took-off his RWD-5bis from Okęcie Airport in Warsaw, and headed Lyon, France – opening the first stage of his long and lonesome flight to Brazil. After two weeks of his journey – flying through Lyon, Perpignan, Casablanca and Port Etienne – Skarżyński reached St. Louis in Senegal. Nevertheless, the longest and most difficult leg of his flight was still yet to start…

The big day for the Polish pilot has come on 7th May 1933. Supplied with some fruits and sweets, being equipped with a headlamp (one of the most important items for this transatlantic flight, taking into the consideration the lack of instrument panel backlight), Stanisław Skarżyński took-off from St. Louis at 11:00 p.m. GMT – beginning his flight across the Atlantic Ocean. However, he still did not disclose his real destination, officially heading for Western Europe.

Taking-off at such a late hour was not random. As the flight was expected to last more than a dozen hours, beginning it at the nightfall should help the pilot to overcome sleepiness. The small aeroplane was flying on a 240-degree course and because of the fog, Skarżyński was initially flying at the altitude of 50 – 100 metres above the ocean.

At around half an hour before the sunrise, he climbed and continued the flight at altitude between 1,700 and 2,500 metres, compensating the course for the wind. Most of the time, it was impossible to find any orientation points and Skarżyński had to rely solely on his calculation nad navigation skills.

After twelve hours of flying over the ocean, Skarżyński spotted some small islands, but they were barely recognisable on the map. Only at 4:00 p.m. GMT the mainland appeared on the horizon and RWD-5bis reached it at 4:15 p.m. – officially crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Skarżyński realized he was between Cape São Roque and Natal, therefore veering only 15 kilometres off the initial course. An exceptional achievement, taking into the consideration he made it after flying more than 3,000 kilometres over the sea, in the night and without any orientation points.

Skarżyński initially planned to land at Natal, but having still about 150 litres of fuel, he decided to extend the flight to Maceió. After another three hours of flight, at 7:30 p.m. GMT, the small silver bird landed in the capital of the coastal state of Alagoas, Brazil. Stanisław Skarżyński now officially became the first Polish pilot to cross the Atlantic Ocean. He still have enough fuel for a few additional hours of flight but was afraid to continue the journey beyond Maceió, flying over the unknown land in the evening.

Obviously, he was not enthusiastically welcomed by any crowds there. In fact, the airfield seemed to be quite deserted, but after a while the airport service representative appeared. When Skarżyński, a lone man, dressed in a casual suit and bareheaded, announced that he is a Polish Air Force captain that just came directly from St. Louis de Senegal, no one believed him at first.

Although Maceió was informed about the possible flight across Atlantic, the airport authorities expected a large, transatlantic aeroplane. Only after checking the RWD-5bis registration, all become clear. Shortly thereafter, an airport commandant arrived from the city to meet Skarżyński and assist the Polish pilot with arranging some formalities needed to officially recognize the record flight – checking the seals on the aeroplane and securing the barogram by varnishing it (barogram was then a common method of recording flight altitude, by the variations of atmospheric pressure for a given time).

On the next day, the official documents necessary for recognizing Skarżyński´s achievement as the record flight, were signed by the airport commandant, French consul in Maceió and the airport radio station manager. The 3,640 km route from St. Louis to Maceió was flown in 20 hours and 30 minutes at an average speed of 177.6 kph, including 17 hours and 15 minutes over the Atlantic Ocean.

Captain Stanisław Skarżyński became the first Polish pilot ever to cross the Atlantic. In addition, RWD-5bis was at that time the smallest and lightest aircraft that flew across the Atlantic Ocean. Skarżyński also set up another record of non-stop flight distance in FAI Category II – tourist aircraft, unladen weight up to 450 kg. Eventually, the entire route from Warsaw to Rio de Janeiro made it 17,885 kilometres travelled in the air (18,305 km if to include the returning flight from France to Poland).

Skarżyński did not return to Poland immediately, staying in Brazil for the next few weeks. As the news about his unique flight hit the press, he was flying across the country, visiting Rio de Janeiro, Santos, Curitiba, Porto Alegre or Buenos Aires and attending meetings there. The brave Polish pilot was welcomed by Stanisław Grabowski, the Polish envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary and also met with Getúlio Vargas, the President of Brazil. During this tour across Brazil Skarżyński was finally being greeted by the crowds at every place he and his RWD-5bis appeared, once even being accompanied by three DH-82 Tiger Moths of the Brazilian Air Force.

On the way back, the RWD-5 bis and his pilot crossed the Atlantic Ocean aboard the ´Avila Star´ liner. Then, from the French airfield in Boulogne, Skarżyński again took-off in his tiny aeroplane and headed Poland. His incredible adventure was officially finished on 2nd August 1933, when the silver RWD-5bis landed at Pole Mokotowskie in Warsaw. However, on the way back to Warsaw, Skarżyński made a short stopover in Lublinek, near Łódź, where he was warmly welcomed by his wife Julia. Certainly, after returning to Poland, Skarżyński was enthusiastically welcomed and shortly become a well-known, public person. However, being rather a humble person, he was not comfortable with this situation.

Less than a year after that historic flight, Skarżyński returned to active military duty and was promoted to the rank of major on 5th March 1934. Then he finished the Higher School of Aviation in Warsaw and again was assigned the commander of a combat squadron.

Over the next years, his military career proceeded smoothly. In 1938, Skarżyński became the Deputy Commander of the 4th Aviation Regiment in Toruń. Later the same year, he was appointed lieutenant colonel. Apart from his military duties, Skarżyński was also actively involved in sport aviation, finally becoming the President of the Aero Club of the Polish Republic, since 26th April 1939.

During all those years he was widely admired as aviation pioneer and adventurer, often nicknamed as ´Polish Lindbergh´. In 1936, with the establishment of Louis Blériot medal in France – awarded to record setters in speed, altitude and distance categories in light aircraft – Skarżyński was among the first four recipients of it, still being the only Polish pilot awarded with that medal.

Skarżyński´s adventures were documented in two books he wrote. His first publication, ´25,700 kilometres over Africa´, told about the African tour of 1931 and the second book entitled ´Across the Atlantic with RWD-5´ was sharing his memoirs from the record-breaking flight.

And interestingly, Skarżyński acted as a model for the Monument of Aviators in Warsaw, designed by Edward Witting and erected in 1932.

In August 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the World War II, Skarżyński was additionally assigned the Chief of Staff of the Pomeranian Army and he held this position during the Invasion of Poland. After the defeat of Poland, Skarżyński was evacuated to Romania, sharing the fate of many other Polish soldiers. There, acting as Deputy Air Force Attaché, he coordinated the transfer of Polish pilots to France.

Eventually, Skarżyński followed the same path, and in 1940 came to France, soon becoming the Deputy Chief of Staff in the Polish Air Force there. The French episode was, regrettably short, and after the fall of France he set off for the Great Britain, together with many other Polish refugees.

Shortly after arriving to Britain, Skarżyński was assigned a new task of educating Polish cadet airmen and become the commander of their training course. The experience and flying skills of the pioneer aviator were supposedly noted by Polish authorities as a valuable asset, so it seemed that Skarżyński´s future career would be related to pilot training.

At the beginning of 1941 Skarżyński was transferred to Polish Flying Training School at RAF Hucknall and assigned the post of Chief Flying Instructor. With the development of the Polish Air Force, the flying school at Hucknall was soon split into No. 25 Polish Elementary Flying Training School at RAF Hucknall and No. 16 Polish Secondary Flying Training School at RAF Newton. Skarżyński was initially assigned to 16. PSFTS, then becoming the Polish commander of RAF Hucknall.

However, the flying school environment was not enough for such an adventure pilot as Skarżyński was. He asked several times for being transferred to a combat post and finally the prayers were answered – in April 1942 Skarżyński was appointed the commanding officer of RAF Lindholme, in the rank of Acting Group Captain.

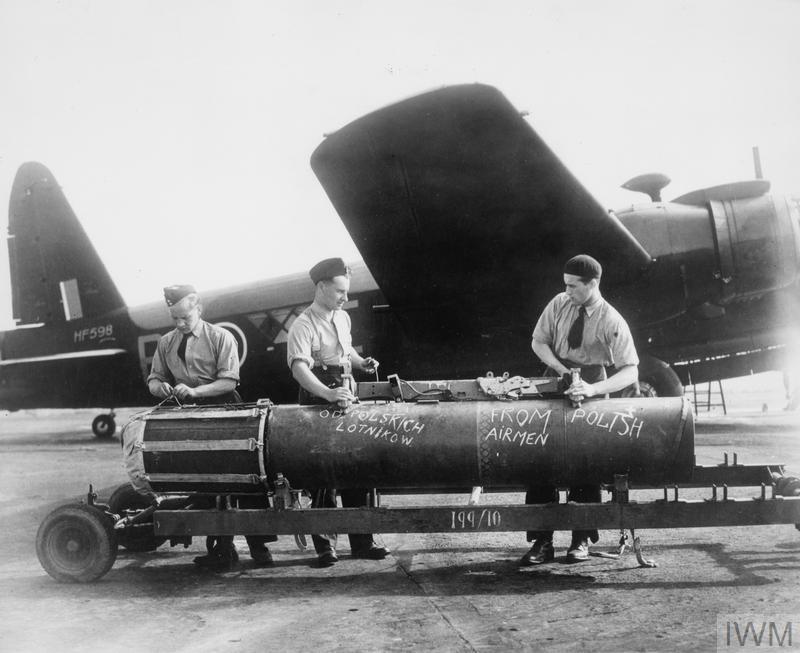

Lindholme was then a home for two Polish bomber squadrons, flying Vickers Wellington aircraft – No. 304 (Polish) Bomber Squadron RAF ´Ziemi Śląskiej´ (the Land of Silesia) and No. 305 (Polish) Bomber Squadron RAF ´Ziemi Wielkopolskiej´ (the Land of Greater Poland) – that arrived there in July 1941. Those two Polish squadrons were operating hand-in-hand from Lindholme until May 1942, when 304 was transferred to the Coastal Command.

No. 305 Squadron remained the only squadron at the base and during the next two months worked intensively in a joint effort of the RAF Bomber Command. Among other missions taking part in the first ´thousand-bomber-raid´ against Cologne in May, then in the second one against Essen, on 1-2 June.

Presumably, the commanding officer duties did not allow Skarżyński to fly on a regular basis. He managed to fly just a few missions in May and June with No. 305 Squadron, as an additional crew member. At the beginning of May he accomplished three raids over France, with targets in Paris and Nantes. Then, during the night of 30-31 May, Skarżyński participated in the first ´thousand-bomber-raid´ ever, the famous ´Operation Millennium´ over Cologne. The day after, in the night of 1-2 June, he completed the second ´thousand raid´ to Essen, dropping bombs through the clouds at the altitude of 18,000 feet. Most of those missions were flown in the Wellington Z8339, SM-N.

The third ´thousand-bomber-raid´ of the summer offensive was scheduled for the night of 25-26 July. The target of that night was Bremen – the north German harbour town, despised by the Bomber Command crews for its extremely heavy anti-aircraft defence.

In order to meet the demand for another spectacular air raid, the Bomber Command planned to use all available aircraft, including Blenheims, Hampdens, Whitleys and Bostons. However, this still made just 960 aircraft. After the personal intervention of Winston Churchill, the Coastal Command additionally assigned 102 of its aircraft for Bremen.

Among 1,067 bombers that took-off this night for Bremen, was Vickers Wellington Mk.II Z8528, SM-R, commanded by F/Lt Edward Rudowski. However, for this raid it had an additional crew member – after a gap of almost one month, G/Capt Stanisław Skarżyński joined the crew for his third ´millennium raid´. The records about this flight are not clear, but most probably the Wellington was captained by P/O Józef Szybka, with Skarżyński being his second pilot and Rudowski took the position of the gunner.

During the third ´thousand-bomber-raid´ the Bomber Command lost 48 aircraft, including the Wellington SM-R, the sole loss of No. 305 Squadron. There are many versions about what happened this night, that could be found in publications and studies about Skarżyński and his life. Sadly, most of them stretches the truth while telling about the last flight of ´Polish Lindbergh´.

The Vickers Wellington SM-R took-off at 23:15 hours, as the first one from the squadron and carrying one 4,000 lbs bomb (commonly nicknamed as ´cookie´). On the way to the target, somewhere over the Dutch coast, the left engine stalled. The crew had no other choice than abandon the mission and, after jettisoning the ´cookie´, set course back home.

Sadly, the pilot was not able to maintain the altitude and SM-R, reportedly piloted by Skarżyński himself, at 02:00 hours ditched in the North Sea, 14 miles off Yarmouth (however, the Operations Record Book of the squadron indicates 40 miles). The sea was heavy that night, but the crew managed to abandon the aircraft, and board the dinghy launched by the navigator. All but one – while leaving the aircraft Skarżyński was hit by a wave and washed to the port side of Wellington.

Although the official Bomber Command records say laconically that ´Skarżyński was hit by a wave as he left the aircraft and was drowned´, the very end of his life was probably a much bitter moment. The crew of SM-R reported that they could hear Skarżyński calling for help for about thirty minutes. Sadly, it was neither possible to determine his position nor to control the dinghy turning randomly on the rough sea.

The Polish airmen were then found by Sgt Marchand from No. 279 Squadron, flying the air-sea rescue Lockheed Hudson aircraft. A Lindholme gear was jettisoned for them, landing just 4 yards away, but the sea was so heavy that the Wellington crew could not reach it. They were finally rescued a bit later, picked up by a high-speed-launch – eight hours after abandoning the aircraft, according to the Operations Record Book. Skarżyński´s body was carried back by the North Sea streams and washed up on Isle of Terschelling, the Netherlands. He was buried at West-Terschelling General Cemetery, grave No. 62.

Admittedly, operational flying in the Bomber Command was extremely dangerous duty. The death rate among the crews within the Command exceeded 44 percent. Regrettably, Skarżyński was among those that never got the chance to finish his combat tour.

Stanisław Skarżyński was posthumously awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta 2nd Class and promoted to the rank of colonel. This was the final addition to the long list of his awards, including the French Legion of Honour, the Brazilian National Order of the Southern Cross, the Order of the Crown of Romania and many others.

Nowadays, the remembrance about the brave pilot is still alive in Poland. Skarżyński is the patron of Aeroclub in Włocławek, was a patron of the 13th Airlift Regiment of the Polish Air Force (1985 – 2000), the 13th Airlift Squadron (2001 – 2010) and finally the 8th Air Transport Base in Kraków (since 2012). In most of Polish cities the street named after him can be found and in addition Skarżyński is also a patron of several schools, colleges and scouting teams.

The famous midget aircraft that crossed the Atlantic, later nicknamed ´Amerykanka´ (an American woman) was – after the record flight – again restored to the standard, two-seat variant, and donated to Skarżyński as a gift. When the war broke out, the last known location of SP-AJU was at the Lviv airport (now Ukraine). The city was then captured by the Soviet Army on 23rd September 1939 and the further fate of silver RWD-5bis remains unknown.

On 26th August 2000, the replica of Skarżyński´s aeroplane, designed as RWD-5R (R meaning ´replica´) took-off for its maiden flight. In appearance, this aircraft was almost identical to SP-AJU, with just small details changed, as required by the current aviation regulations. Over the next years SP-LOT, as the replica was registered, was a frequent participants of the Polish air shows and was also offered for the sightseeing flights. Unfortunately, on 1st September 2018, during the air show in Bielsko-Biala, the RWD-5R SP-LOT crashed. Fortunately, two persons on board went without any injures, but the aircraft was heavily damaged and was not repaired until today. Hopefully, according to some initial statements the aircraft is planned to be repaired and yet restored to flying condition.

Sources:

-

- Tom Docherty, Dinghy Drop: 279 Squadron RAF, 1941–46

- Peter Jacobs, Bomber Command Airfields of Yorkshire

- Martin Bowman, The Heavy Bomber Offensive of WWII

- Martin Bowman’s comprehensive study of Bomber Command: Reflections of War: Battleground Berlin (July 1943 – March 1944)

- No 305 Squadron: Operations Record Book

- International Bomber Command Centre, online resources

- Jerzy Cynk, Polish Aircraft 1893-1939

- Wikipedia – The Free Encyclopedia

- Cover photo and photos 8, 9 by Bartek Gawrylczyk