On 28th April 1910, at 5:32 a.m., Louis Paulhan landed his aircraft at Barcicroft Fields near Manchester, winning the Daily Mail contest and, at the same time, the first long-distance aviation race in England.

On 28th April 1910, at 5:32 a.m., Louis Paulhan landed his aircraft at Barcicroft Fields near Manchester, winning the Daily Mail contest and, at the same time, the first long-distance aviation race in England.

At the dawn of aviation, many big newspapers and magazines used to sponsor prizes for those who dared to push the limits forward. It was quite popular way to attract readers but, at the same time, stimulating the new inventions and adventures.

Although the powered, heavier-than-air aircraft was one of the latest and yet not developed inventions, it quickly found its way to front pages of newspapers. The quarter mile out and return flight, the first flight across the English Channel, the first circular one-mile-flight, the longest flight performed by a woman pilot (Femina Cup), the first flight performed by British pilot in a British-made aeroplane, the first transatlantic flight – were only a few of aviation milestones that were motivated by newspaper-founded prizes.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Daily Mail – the British daily middle-market newspaper founded in 1896 – was among the most active sponsors of aviation competitions. Between 1906 and 1930, following the initial idea of Alfred Harmsworth, the owner of the Daily Mail, the newspaper set more than twenty aviation goals, each of them awarded by a considerable amount of money.

And to mention just a few of them: in 1908, the Daily Mail awarded 1,000 GBP (current equivalent of approximately 110,000 GBP) to Louis Blériot for cross-channel flight. In 1911, Jean Louis Conneau (aka André Beaumont) won 10,000 GBP (more than a million pounds in today´s equivalent) for winning Circuit of Britain cross-country air race organized by that newspaper. And in 1930, Amy Johnson was awarded with 10,000 GBP (current equivalent of approximately 672,000 GPB) for her solo flight from England to Australia.

The first aviation prize sponsored by the Daily Mail was set already in 1906. The newspaper offered 10,000 GBP (almost 1,1 million GBP in today´s equivalent) for the aviator who would be the first to fly a distance of 298 km (185 miles) from London to Manchester, under following conditions: the flight cannot take more than twenty-four hours, no more than two stops have to be made and, last but not least, take-off and landing must be at a location within five miles from the Daily Mail offices in both towns.

Nowadays, those achievements, as well as the conditions and the amount of the prize, can seem a bit peculiar, but they were of great importance in those early years of aviation. The first flight of powered, heavier-than-air aircraft built by the Wrights took place only three years earlier and covered a distance of thirty-seven metres. In 1906 – the year the Daily Mail prize was announced – Traian Vuia and Jacob Ellehammer built their first aircraft and managed to fly twenty-four and forty-two metres, respectively. In November of the same year, Santos-Dumont set the first official flight distance record recognized by the FAI. And it was… 220 metres.

Therefore, it was not surprising that the Daily Mail offered such a large amount of money for the flight on a distance more than a thousand times longer. For a few years, the goal set by the Daily Mail editors remained only a curiosity and there was no aviator to respond to that call.

Only in 1910, two pilots decided to take up the gauntlet and fight for the prize. At that time, both men that entered the Daily Mail competition were already quite famous and experienced aviation pioneers, with their skills well-proven.

The first of them was Claude Grahame-White, an Englishman who, inspired by Blériot and his cross-channel flight, went to France to learn how to fly. In January of 1910 Grahame-White became one of the first licensed English aviators, with Royal Aero Club pilot´s certificate No. 6. Shortly after, he also founded his own flying school.

A Frenchman named Isidore Auguste Marie Louis Paulhan was the second pilot, in the same way famous of his various aviation experiences. Paulhan was a balloon pilot during his military service and worked as an engineer on development of French dirigibles. He also was making model aircraft and attended related competitions – an activity that eventually allowed him to win a Voisin airframe.

In a short time, Paulhan bought an aviation engine for the aforementioned airframe and learned how to fly. In 1909, he received the French aviation licence No. 10 and started his pilot´s career. Within a year he managed to set several records for flight altitude, distance and speed. In addition, Louis Paulhan travelled through Europe and the USA, attending the first air shows and public flying displays.

If you read an article from our Aviation History Friday series, focused on William Edward Boeing, you may recall a passage telling the story of young Boeing walking from one aircraft to another during an air show, asking every single pilot for a ride. Regrettably, everyone turned him down, including Paulhan. The French aviator initially agreed to take Boeing into the skies and promised to do that after the show. Nevertheless, he left the show shortly after his display, leaving Boeing disappointed. And we will never get a chance to find out what would happen if they performed a flight together.

Returning back to our main story – roughly at the same time Paulhan and Grahame-White decided to fight for the Daily Mail prize. Although they were aware of each other, initially nothing indicated the attempt to fly from London to Manchester turns into a real air race.

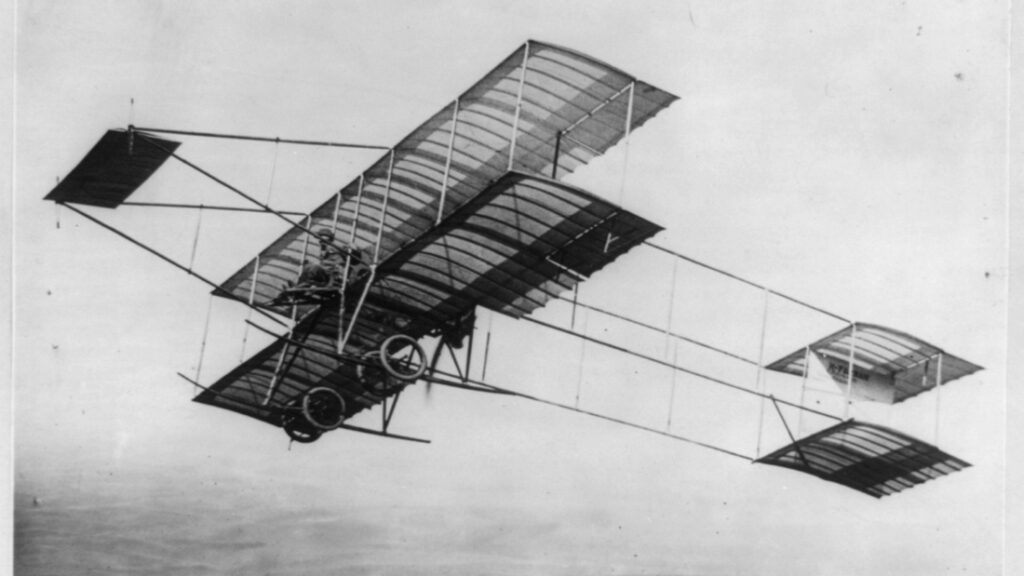

At 5:12 a.m., on 23rd April 1910, Claude Grahame-White took-off for his first attempt to win the Daily Mail prize. The aircraft he chose for the flight was Farman III biplane, powered by 50 hp rotary engine. Grahame-White´s pre-flight preparations, despite the early morning hour, were observed by Henry Farman himself.

At 7:15 a.m., Grahame-White made the first stop at Rugby, quickly attracting attention of quite a big crowd of spectators. About one hour later, the English pilot took-off for the next stage of the flight but managed to cover only approximately fifty kilometres. Problems with the engine forced Grahame-White to land at Hademore. What´s more, he also damaged the undercarriage skid during the landing.

His technical team that arrived there shortly after managed to repair the aircraft until evening. Regrettably, the weather turned worse and strong wind prevented Grahame-White from taking-off. He stayed up the whole night, waiting for the wind to calm down but eventually gave up around 3:00 a.m., when he was aware it was impossible to reach Manchester within the required twenty-four hours from the starting point.

On 25th April, when Grahame-White aircraft was still undergoing some maintenance, two new actors appeared on the stage. They were Louis Paulhan, who just arrived from California, and Emile Dubonnet, another French pilot that entered the contest.

On 27th April, Paulhan´s aircraft – also a Farman III – was assembled at Hendon. The French pilot began his journey with no delay. At 5:21 p.m., Paulhan took-off and headed Harrow, his official starting point.

It should be mentioned here that Paulhan´s attempt was really well-prepared. He planned to fly along the London and North Western Railway route, so railway company was asked to paint sleepers white to mark the correct direction of the flight. Paulhan´s aircraft was followed by a special train with his wife and Henry Farman aboard, while rest of his team travelled in cars.

On the same day, but in the morning, Grahame-White was planning to perform test flights with his aircraft. Regrettably, the crowd gathered at Wormwood Scrubs field made the flight impossible, so the English pilot returned to his hotel. There, approximately at 6:00 p.m., he was noticed that Paulhan just started his attempt. Not thinking twice, Grahame-White run to his Farman and engaged in pursuit. The first air race in England just began.

Grahame-White was approximately one hour behind the Frenchman, but he knew that no aircraft could make the London to Manchester route without any stops. Therefore, he still had a chance to win the race.

By nightfall, both aviators had to find a suitable place to land. Grahame-White landed at Roade, near the aforementioned railway line, and Paulhan stopped somewhere one hundred kilometres ahead, at a field next to Trent Valley railway station. Both pilots initially planned to resume their journey with first ray of sunlight.

Nevertheless, to increase his chances, Grahame-White made a risky and then incredible decision to fly during the night. Instead waiting for the sunlight, the Englishman took-off at 2:50 a.m. and continued to fly along the railway route, using the railway station lights as guidance.

Regrettably, the Grahame-White aircraft was carrying too much fuel and thus the engine was not enough powerful to overfly the high ground on the way. The English pilot was forced to land near Polesworth, just sixteen kilometres behind Paulhan.

At the same time the Frenchman, completely unaware of Grahame-White progress, took-off for the final stage of his flight. At 5:32 a.m. on 28th April 1910, Louis Paulhan landed his Farman III at Barcicot Fields near Didsbury, therefore winning the contest. Informed about Paulhan´s success, Grahame-White sincerely congratulated the Frenchman and then abandoned his attempt to continue journey to Manchester.

Emile Dubonnet, the third pilot to attempt the competition, was too late with his flight arrangements and, faced with Paulhan´s victory, did not enter the race.

The 1910 London to Manchester air race had been widely echoed all over the word. It marked the first long-distance air race in England, the first take-off of powered, heavier-than-air aircraft during the night, as well as the first powered flight to Manchester.

On 30th April 1910, during a solemn ceremony at Savoy Hotel in London, Louis Paulhan was awarded his main prize of 10,000 GBP. Grahame-White received a consolation prize of white-silver bowl.

After the race, Paulhan continued with his aviation adventures. He was one of the first pilots in the world to fly a seaplane and shortly after opened his own seaplane flying school in France. During the Great War, Paulhan served as pilot over France and Serbia, then returned to develop aircraft parts for the French military.

When the Great War was over, Paulhan focused on making the seaplanes for different manufacturers. He was also a co-founder of Société Continentale Parker company (later known as Coventya) that was developing surface treatments for aviation. In 1937, after tragic death of his son during presentation of Caudron C.690 fighter, Louis Paulhan abandoned further aviation career and retired to Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

In April of 1950, on the 40th anniversary of his famous flight, Louis Paulhan repeated his journey from London to Manchester, this time on board of a British military jet, Gloster Meteor T7. This time, the flight lasted much shorter, as the Meteor flew the route at 644 kph.

Isidore Auguste Marie Louis Paulhan died on 10th February 1963, at Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

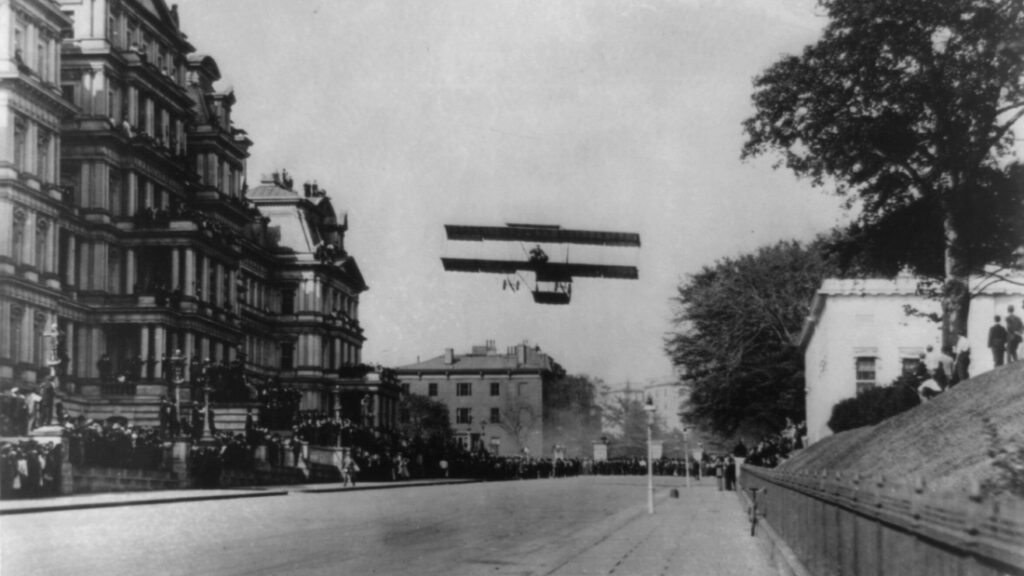

Claude Grahame-White also continued his aviation career. Yet in 1910 he won 1,000 GBP prize for Aggregate Duration in Flight, with one hour, twenty-three minutes and twenty seconds. Later that year the British pilot toured the United States, where he made a bit controversial but famous stunt of flying over Washington D.C. and landing near the White House. He also founded his own aviation company and built several aircraft.

During the Great War Grahame-White was an active military pilot and promoter of military aviation. He flew the first British night patrol mission, trained several women to fly by establishing Women´s Aerial League.

After the war, Grahame-White entered a long legal dispute with the British military authorities that wanted to take over his private airfield for military purposes. Eventually, the airfield was purchased by the Royal Air Force in 1925. Grahame-White, tired of that legal battle, lost interest in aviation and moved to Nice, the French Riviera. There, he successfully devoted himself to property development, acquiring a fortune.

Claude Grahame-White died on 19th August 1959, in Nice.

Shortly after Paulhan´s victory in London to Manchester competition, the Daily Mail newspaper offered a new prize. This time, the amount of 10,000 GBP was offered to the first aviator to cover a thousand-mile (1,609 km) circuit of Britain in a single day.

That task was completed on 26th July 1911 by French pilot Jean Louis Conneau (aka André Beaumont), who flew the required distance in twenty-two and a half hours.

Sources: Daily Mail, Flight, The Times and New York Times archive issues from 1910, Wikipedia.

Cover photo: Paulhan aeroplane taking off, Los Angeles, Calif., Library of Congress (George Grantham Bain Collection LC-B2- 950-15)