When we think about the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean, usually Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis aeroplane are the first that come to our mind. His feat stuck in common perception to such a degree that Lindbergh is usually the only one being associated with pioneering transatlantic flight. Even the AI chatbots – that became more and more popular recently – tell the Lindbergh´s name when asked who was the first to fly across the Atlantic. Just confirming his popularity as the icon of the transatlantic flight.

When we think about the first flight across the Atlantic Ocean, usually Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis aeroplane are the first that come to our mind. His feat stuck in common perception to such a degree that Lindbergh is usually the only one being associated with pioneering transatlantic flight. Even the AI chatbots – that became more and more popular recently – tell the Lindbergh´s name when asked who was the first to fly across the Atlantic. Just confirming his popularity as the icon of the transatlantic flight.

But was Lindbergh really the first pilot to fly across the Atlantic Ocean? Certainly, he was not. Lindbergh was the first to perform a solo, non-stop flight on route from New York to Paris. Without any doubts that was a spectacular feat and no one underestimates its importance. Nevertheless, Charles Lindbergh was not the first one to cross the Atlantic.

It may seem surprising but approximately eighty (sic!) people that crossed the Atlantic Ocean in an aircraft yet before Lindbergh. And even more extraordinary is, their names are nearly forgotten for the public and media, with only some historians and aviation enthusiasts that are still aware of them.

In fact, the idea of transatlantic flight appeared along with development of hot air balloons. John Wise, an American ballooning pioneer, was among the first who were aware of existence of jet stream – a fast air current between America and Europe – that could make such a flight possible. In the end of 1850s, Wise built an aerostat, specially designed for the purpose of transatlantic flight and named Atlantic. However, that balloon crashed in 1857 (or 1859, according to some sources) during its test flight and was never repaired.

In 1860, Thaddeus Lowe followed his steps and built a huge balloon of capacity exceeding 20,000 m³, named City of New York. Lowe was going to make an attempt to fly across the Atlantic next year, but his plans were cancelled due to the Civil War.

Another noticeable attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean was performed in 1910 by Walter Wellman, an American journalist, adventurer, polar explorer and aviation pioneer. On 15th October, the non-rigid airship America set out from Atlantic City in New Jersey, carrying onboard Wellman, his crew and also a cat named Kiddo.

Regrettably, after thirty-eight hours of the flight, engines of the America failed and the airship started to drift south. The crew, including the cat, abandoned the airship. They were rescued by the British steam ship, that picked the America crew somewhere west of Bermuda.

Opportunities to conquer the Atlantic air route changed significantly with development of heavier-than-air, powered aircraft. Flight distance records were being broken every year, slowly coming closer to numbers that allowed to believe the transatlantic flight is possible.

In April of 1913, the Daily Mail newspaper officially opened the transatlantic flight competition. The editorial office offered an award of 10,000 GBP – an equivalent of almost 1.5 million GBP in current value – to ´the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an airplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland to any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours´. The prize boosted some aviation pioneers to design aircraft able to fly across the ocean. However, the outbreak of the Great War stopped their works and caused the competition was suspended for a couple of years.

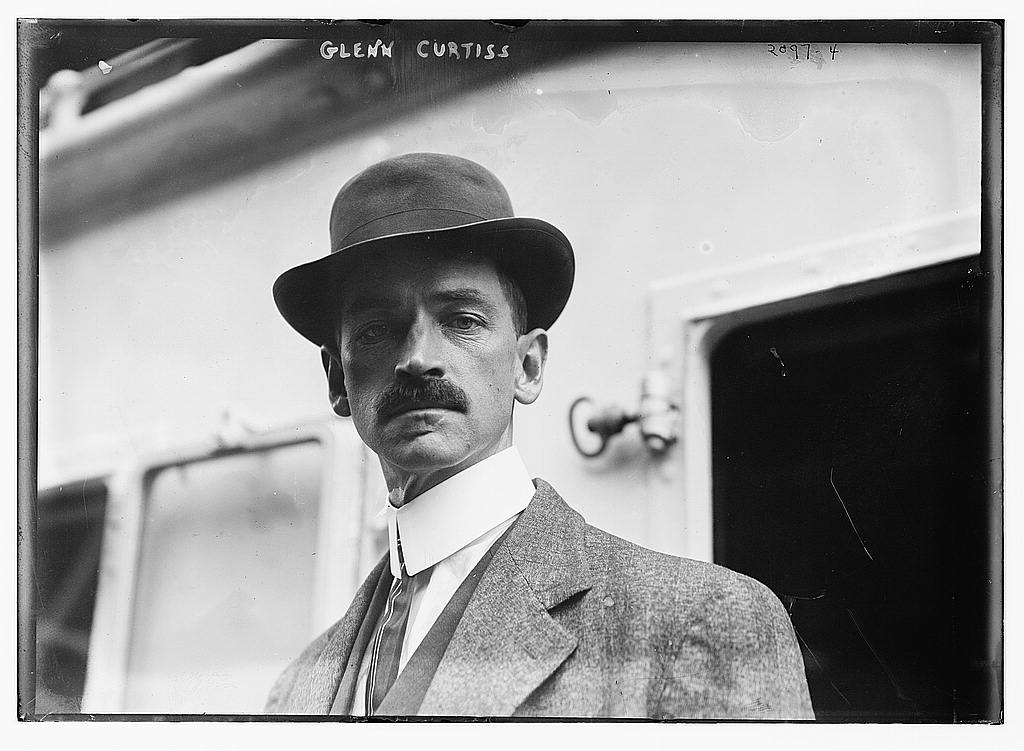

At the end of the war, the US Navy asked Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company to build an anti-submarine warfare aircraft able to perform long ocean patrol flights. Such a need resulted from war experiences and troubles that German submarines caused to Allied powers. One of additional requirements was that, in case of any next war, the new aeroplane should be able to fly from America to Europe on its own.

Glenn Curtiss was already working on some floatplanes since 1908. In the beginning of the 1910s, his construction team expanded to include John Cyril Porte, Emmit Clayton Bedell and John Towers. In 1914, they made a flying boat designated America and hoped to compete for the Daily Mail prize.

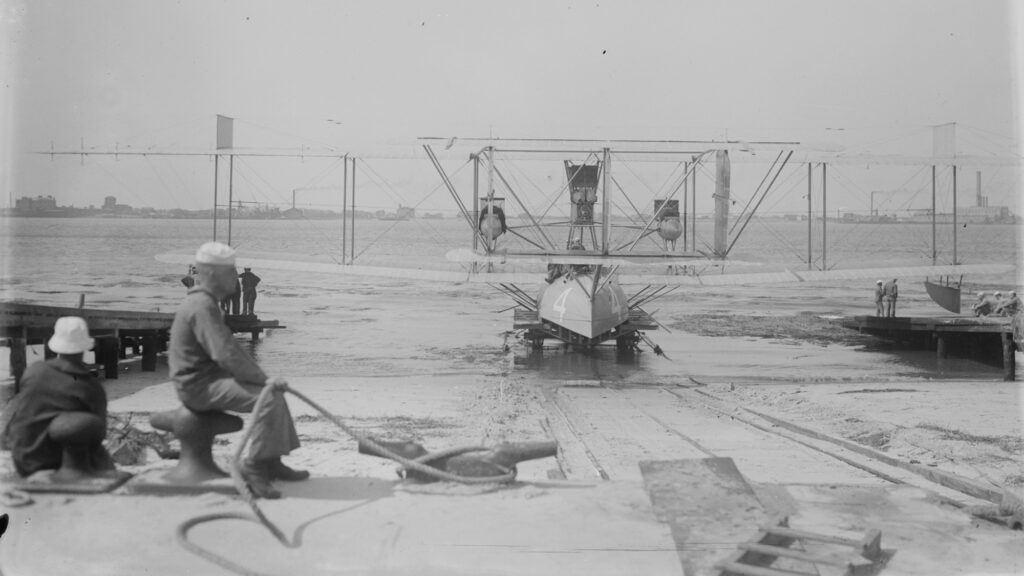

In 1918, drawing on the experience gained by working on their previous aircraft, the Curtiss team developed a flying boat, officially designated Curtiss NC – with N standing for the Navy and C for Curtiss – but commonly known as ´Nancy boat´ or just ´Nancy´. On 4th October 1918, the NC-1 successfully completed its maiden flight.

The Curtiss NC was operated by a crew of five. The aircraft was powered by four Liberty L-12A water-cooled V-12 piston engines, each of them generating 400 hp. Its maximum take-off weight exceeded 12,000 kg, maximum speed was its (85 mph) and expected flight endurance had to exceed fourteen hours.

In order to prove the long-distance capability of the new flying boat, the Navy and the Curtiss company started their cooperation on transatlantic journey. It had to be a demonstration flight to show the abilities of the new aeroplane. Initially, it was intended that four examples of the aircraft – NC-1 to NC-4 – would fly across the Atlantic, however the NC-2 was damaged beyond repair during testing.

Therefore, on 8th May 1919, not four but three Curtiss flying boats began their flight across the Atlantic Ocean. The route led from New York City, through Rockaway Naval Air Station, Massachusetts, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and the Azores, to Portugal. Several US Navy ships were located along the way to help the crews to navigate, as well as support them in case of emergency.

On 15th May, the aircraft arrived to Newfoundland. On the following day the three flying boats began the most challenging part of the route, from Newfoundland to the Azores. However, during that leg, two aeroplanes were forced to land on the open sea because of severe weather conditions and mechanical issues. Only the NC-4 made it to Faial Island in the Azores after 15 hours and 18 minutes of flight. On 27th May, after completing some necessary repairs, the NC-4 flying boat took-off for the last leg to Lisbon. The aeroplane reached the capital of Portugal after 9 hours and 43 minutes of flight.

The Curtiss flying boat NC-4 was the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic Ocean and, at the same time, the first one that flew from the North America to Europe mainland-to-mainland (officially beginning in Massachusetts and with final landing in Lisbon). It took the NC-4 almost 11 days to fly from Newfoundland to Portugal, but the ´net´ flying time was just 26 hours and 46 minutes. That significant milestone in aviation history was made by the crew of Albert Cushing Read (commander), Walter Hinton and Elmer Fowler Stone (pilots), James L. Breese and Eugene S. Rhoads (flight engineers) and Herbert C. Rodd (radio operator).

Certainly, the record flight of the NC-4 was not counted for the Daily Mail competition due to the time it needed to cross the ocean. Nevertheless, competing for that prize was never among the US Navy goals and completing the flight within the stated limit of 72 hours was not the priority.

However, at the time the NC-4 successfully completed the first transatlantic flight in history of aviation, at least four teams entered the Daily Mail competition. What´s more, two attempts to cross the Atlantic were made on 18th May, definitely inspired by the US Navy demonstration flight.

The first were Australian pilot Harry Hawker and his British observer Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve. They took-off from St. John airfield on Newfoundland with experimental Sopwith Atlantic aeroplane, developed from Sopwith B.1 bomber. However, they suffered some problems with engine and were forced to ditch in the Atlantic near the Danish ship they encountered on the way.

The second crew that made its attempt on the same day of 18th May was Frederick Raynham and C.W.F. Morgan. Their aeroplane was Martinsyde Buzzard A.Mk 1, specially modified for the purpose of the transatlantic flight. Regrettably, they crashed the aircraft during take-off due to exceeding maximum take-off weight.

Almost one month later, on 14th June 1919 in the afternoon, John Alcock and Arthur Brown took-off from the same St. John´s airfield, flying a modified Vickers Vimy F.B.27A Mk IV, twin-engine bomber designed during at the final stage of the Great War. Their attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean was officially backed by Vickers and Rolls-Royce, the manufacturer of aircraft engines.

Just as in the previous case, the Vimy seemed to be overloaded. The aeroplane took-off with difficulties, narrowly missing trees at the end of runway. In addition, shortly after beginning of their journey, the wind-driven electric generator broke down, leaving Alcock and Brown without radio, intercom and heating.

The flight was very challenging and abundant in dramatic events. The crew was almost frozen, at least two times lost control of the aircraft and had to deal with several small, nevertheless annoying and distracting, technical issues. In addition, the Vimy was equipped with minimum necessary flying instruments, thus forcing Brown to navigate by the stars. Although, when the aircraft reached a heavy fog area, and then snowstorm and rain, that kind of aerial navigation became impossible.

However, and against all odds, Alcock and Brown did it. In the morning of 15th June, the Vimy successfully landed in County Galway in Ireland. The first non-stop transatlantic flight was completed, after 15 hours and 57 minutes in the air and covering the distance of 3,040 kilometres. It should be also mentioned here that the Vimy carried some mail onboard, making the flight also the first transatlantic air mail service.

John Alcock and Arthur Brown soon became heroes of aviation. They not only received the Daily Mail reward money but also were awarded with a few more cash prizes. In recognition of their merits, Alcock and Brown were also knighted by King George V. Regrettably, John Alcock was able to enjoy the fame of Atlantic conqueror for just a short time – he died in an aviation accident on 19th December 1919, flying Vickers Viking aircraft.

In a few weeks, another successful transatlantic flight was completed and set further aviation milestones. On 2nd July 1919, rigid airship type R34 set out from Scotland and headed the North America. The airship was built by William Beardmore and Company and commanded by George Herbert ´Lucky Breeze´ Scott. One hundred and eight hours later, the R34 reached Mineola on Long Island, with almost no fuel left.

The list of ´firsts´ in aviation history achieved by the R34 during that flight is really impressive. It was the first East to West crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by an aircraft, the first transatlantic flight completed by the lighter-than-air aircraft and the first transatlantic flight with passengers, as well as the first transatlantic stowaway, William Ballantyne.

The flight was also marked by parachute jump of one of the R34 crew members, E.M. Pritchard, who was sent on the ground to instruct landing crew at Mineola on how to handle the airship. Therefore, Pritchard became the first person that reached the North America from Europe by air.

What´s more, the R34 marked the aviation history with the first successful transatlantic crossing by a pet animal. A tabby kitten named ´Wopsie´ (aka ´Jazz´), was taken aboard by the aforementioned stowaway and discovered too late to be dropped off.

On 10th July, the R34 set out for return journey to England and reached RNAS Pulham station on 13th July, after 75 hours of flight. That way, the R34 became the first aircraft to complete the two-way crossing of Atlantic.

In 1922, two Portuguese naval aviatiors Carlos Viegas Gago Coutinho and Artur de Sacadura Freire Cabral marked the centennial of Brazil´s independence by the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic. However, the flight needed as much as three aircraft to be completed.

On 30th March 1922, Coutinho and Cabral took-off from Bom Sucesso naval station in Lisbon, flying a Fairey IIID Mk II seaplane they named ´Lusitânia´. Their journey led through the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Santiago Island and then Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago. There, rough ditching caused the aeroplane lost one of its floats and sank. The crew was rescued by a Portuguese cruiser.

The Portuguese government, under pressure of public opinion, decided to send them another Fairey seaplane to complete the journey. It was named ´Pátria´ and, on 6th May, arrived at Fernando de Noronha archipelago, where the Portuguese aviators were staying at that time. A few days later, Coutinho and Cabral took-off in their new seaplane and headed Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, in order to continue their journey from the point it stopped, but engine issue forced them to land on the open ocean. This time, they were rescued by a British ship and carried back to Fernando de Noronha.

The third aeroplane – also the Fairey IIID, this time named Santa Cruz – was sent from Brazil. On 5th June 1922, the Portuguese aviators set out for the last stage of their trip, finally reaching Rio de Janeiro on 17th June 1922.

Crossing of the South Atlantic was then properly completed in 1926, by Spanish aviators in Dornier Do J ´Wal´ flying boat, named ´Plus Ultra´. The crew was Ramón Franco, Julio Ruiz de Alda Miqueleiz, Juan Manuel Durán and Pablo Rada.

During major part of their journey the Spaniards copied the route of Coutinho and Cabral, although their starting point was in Palos de la Frontera in Spain, and they completed the flight in Buenos Aires. The Spanish aviators made that trip in 59 hours and 39 minutes, covering 10,270 kilometres.

On 11th May 1926, a semi-rigid Italian-made airship ´Norge´, commanded by the famous Italian aviation pioneer Umberto Nobile, made the first transpolar flight eastbound. The aircraft set out from Svalbard, flew over the North Pole, and two days later landed in Teller, Alaska. It was also the first flight over the North Pole (check our article from January of 2022, to learn more about Umberto Nobile and his polar expeditions).

In April of the next year, the Portuguese crew José Manuel Sarmento de Beires, Jorge de Castilho and Manuel Gouveia intended to fly across the South Atlantic in the Dornier ´Wal´ flying boat, named ´Argos´.

On 7th March 1927, ´Argos´ took-off from Alverca in Portugal and flew to Casablanca and then Bolama in Portuguese Guinea. There, some technical issues occurred, and their take-off was delayed until late afternoon. The Portuguese crew decided to continue the flight through the night. They reached Fernando de Noronha around midday of next day, after spending 18 hours and 12 minutes in the air and covering 2,595 kilometres. Then, they successfully continued the journey to Recife and Rio de Janeiro. The flight of ´Argos´ marked the aviation history with the first night crossing of the South Atlantic.

The first non-stop flight across the South Atlantic was completed in October of the same year. This time, it was not just another transatlantic journey but part of significantly bigger project of circumnavigating the world.

On 10th October 1927, Dieudonné Costes and Joseph Le Brix began their long journey around the world in Breguet 19 GR (Grand Raid) sesquiplane, named ´Nungesser-Coli´. They crossed the Atlantic Ocean between 14th and 15th October, flying from Saint-Louis in Senegal to Natal in Brazil within 18 hours and covering 3,380 kilometres. It is also worth noticing that their circumnavigation flight was successfully completed on 14th April 1928, with the total distance of 57,410 kilometres flown around the globe.

Back in 1919, just one year after the Daily Mail re-announced its competition, another transatlantic prize was offered. It was established by Raymond Orteig, a French-American hotel owner from New York, and named the Orteig Prize. Orteig offered 25,000 USD – an equivalent of today´s 441,000 USD – for any Allied aviator to fly between Paris and New York, regardless the direction. The offer was valid for five years, but it was considered to be beyond capacity of then existing aircraft and finally nobody entered the competition.

In 1925, Raymond Orteig renewed the prize and this time the offer attracted several aviators, including the famous French World War I flying aces, René Fonck and Charles Nungesser. Regrettably, run for that prize was marked by several tragic accidents that resulted in death of at least six people from the participating crews.

Surprisingly, the Orteig Prize was won by Charles Lindbergh, a relatively little-known air mail pilot from the USA, who crossed the Atlantic in custom-made aircraft named Spirit of St. Louis.

The flight was possible only thanks to financial support provided by businessmen from St. Louis that decided to take the risk and help the unknown pilot to compete for the Orteig Prize. They offered him donation of 15,000 USD, Lindbergh was able to add another 2,000 USD and 1,000 USD was provided by his employer, Robertson Aircraft Corporation. Together it made 18,000 USD – today´s equivalent of 315,000 USD – and meant a fraction of budget available for other competitors. For example, Igor Sikorsky spent approximately 100,000 USD just on development of his S-35 aircraft for René Fonck.

Spirit of St. Louis was designed by Donald A. Hall of Ryan Aircraft Company and officially designated Ryan NYP (New York to Paris). It was a high-wing monoplane, powered by Wright J-5C Whirlwind radial piston engine, generating 223 hp.

On Friday, 20th May 1927, Charles Lindbergh took-off from Long Island for his transatlantic flight. Similar to his predecessors, he had to deal with several issues that occurred during the journey – storm weather, icing and problematic navigation, as well as lack of sleep. Despite all the difficulties, he made it and reached Paris in the morning of 21st May. His flight lasted 33 hours and 30 minutes and covered the distance of 5,800 kilometres.

In Paris, Lindbergh was welcomed by a crowd of approximately 150,000 spectators. He immediately became the world’s hero and then one of the most-recognizable pilots in the entire aviation history. Although, as already mentioned, Lindbergh was approximately eightieth person to cross the Atlantic, for majority of people he is exactly the first person that comes to mind with regards to pioneering the transatlantic flights.

In addition, Lindbergh´s contribution to popularity of long-range passenger flights must be mentioned here. His amazing feat caused many people believed that transatlantic flights are safe and available for passenger aviation. Just the following year, Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschaft – DELAG (English: German Airship Travel Corporation) started with regular passenger flights across the ocean. The first non-stop flight, performed by ´Graf Zeppelin´ airship, took place between 11th and 15 October 1928.

Certainly, Lindbergh´s flight was just another milestone in aviation history. There were many aviators that followed him and contributed to development of the transatlantic flights.

In April of 1928, the German-built Junkers W 33, named ´Bremen´, made the first successful non-stop East to West aeroplane flight across the Atlantic. The aircraft was flown by crew of Ehrenfried Günther Freiherr von Hünefeld, Hermann Köhl and James Fritzmaurice. On 12th April, the W 33 took-off from Baldonnel Aerodrome in Ireland and after 36 hours and 30 minutes reached Greenly Island between Newfoundland and Labrador.

On 18th August 1932, the first solo westbound transatlantic flight was completed. That feat was performed by a Scottish aviation pioneer, Jim Mollison. He flew from Ireland to New Brunswick in Canada in a de Havilland Puss Moth aeroplane, named The Heart´s Content. Mollison´s flight across the Atlantic took 31 hours.

Next year, Polish aviator Stanisław Skarżyński crossed the South Atlantic in a small touring aircraft RWD-5bis. It was part of his journey from Warsaw to Rio de Janeiro and the transatlantic part of the flight lasted 20 hours and 30 minutes.

Skarżyński was not only the first Polish pilot to cross the ocean, but he also set the new record of non-stop flight distance in FAI Category II – tourist aircraft, unladen weight up to 450 kg. At the time of his flight, the RWD-5bis was the smallest and the lightest aircraft that ever flew across the Atlantic Ocean – and with high probability it still remains so (check our article issued in May of 2020, to learn more about Stanisław Skarżyński and his aviation career).

On 4th September 1936, Beryl Markham became the first aviatrix to make a solo flight across the Atlantic. She took-off from Abingdon in England and twenty hours later crash-landed on Cape Breton Island in Canada, fortunately surviving the accident. Markham´s aircraft was Vega Gull touring aeroplane, named The Messenger.

In June of 1937, Valery Chkalov, Georgi Baidukov and Alexander Belyakov performed the first both transatlantic and transpolar flight in an aircraft. They took-off from Moscow on 18th June, flown over the North Pole and then landed in Vancouver, Washington on 20th June. The flight Chkalov and his crew made in Tupolev ANT-25 aeroplane lasted 63 hours and covered 9,130 kilometres.

Then, on 28th April of 1939, V.K. Kokkinaki and M.Kh. Gordienko took-off from Moscow for another northern transatlantic flight to New York. Their aircraft was TsKB-30 ´Moscow´ (ЦКБ-30 «Москва»), modified prototype of a twin-engine long-range bomber, later known as DB-3 (or Ilyushin Il-4). After 22 hours and 56 minutes of flight, Kokkinaki belly-landed on a small Miscou Island, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The transatlantic northern route Moscow – Helsinki – Iceland – Cape Farewell – Miscou Island – New York that was flew by Kokkinaki and Gordienko, is now commonly considered as the shortest way between Europe and America. Since 1965, it is being used for regular passenger transcontinental flights (check our article from April 2021, to learn more about that flight).

On 31st January 1951, Charles Blair Jr. flew his P-51 Mustang warbird from New York to London. He covered the distance of 5,597 kilometres in just 7 hours and 48 minutes, therefore setting the new record for crossing the Atlantic Ocean with piston engine aircraft. The record, that is still current (check our article from May 2020, to learn more about Blair´s record flights of 1951).

The story of transatlantic flights began with the initial, although unsuccessful, attempts to cross the ocean in a hot air balloon. However, it took approximately 120 years to the first balloon crossing of the Atlantic.

Only in 1978, a helium type balloon named Double Eagle II (aka The Spirit of Albuquerque) made it from Presque Isle, Maine to the vicinity of Paris. The balloon was operated by crew of Ben Abruzzo, Maxie Anderson and Larry Newman. That record flight began on 11th August and was completed on 17th August, after 137 hours and 6 minutes of flight.

Cover photo: Curtiss NC-4, the first aircraft that crossed the Atlantic Ocean. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, LC-B2- 4902-17 (cropped).

Information from newspapers and magazines from the era were used, other sources mentioned with previously published and linked articles.